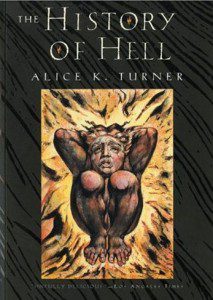

Alice K. Turner’s The History of Hell is not a book of theology. The book draws on several disciplines, with art history, literature and folklore all playing a much larger role than any formal theology. And that’s only fitting, because our idea of “Hell” has been shaped over the centuries far more by art, literature and folklore than it has been by any formal theology.

The word “Hell” is an awkward English translation for several different words in our Bibles. Each of these words — gehenna, Hades, Tartarus — would have meant something quite different to the people who originally spoke, heard, wrote and read them than what the English word “Hell” means to any of us, centuries later. We bring to that word a host of associations they did not have and could never have imagined. Those associations — which seem to us a self-evident part of the meaning of the word — have accrued over the centuries from many sources in folklore, apocryphal writings, medieval visions, mystery plays, paintings, sculptures and great works of genius by Dante, Milton, Bosch, Brugels and others.

The word “Hell” is an awkward English translation for several different words in our Bibles. Each of these words — gehenna, Hades, Tartarus — would have meant something quite different to the people who originally spoke, heard, wrote and read them than what the English word “Hell” means to any of us, centuries later. We bring to that word a host of associations they did not have and could never have imagined. Those associations — which seem to us a self-evident part of the meaning of the word — have accrued over the centuries from many sources in folklore, apocryphal writings, medieval visions, mystery plays, paintings, sculptures and great works of genius by Dante, Milton, Bosch, Brugels and others.

Turner introduces us to many of the more obscure sources that have shaped our idea of Hell — including ancient Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman myths, once-popular pseudoscriptures like the Gospel of Nicodemas, and once immensely popular tales like the vision story of Tundal and his cow.

They may be obscure, now all-but forgotten, but their effect and influence lingers on, shaping what we hear in and what we mean by that word “Hell.” The influence of these sources is intriguing, particularly when contrasted with the paucity of actual biblical material supporting what we say we “know” about Hell. The Old Testament does not appear in Turner’s history. Nor, for the same reason, do the New Testament writings of the Apostle Paul — at least not the biblical Paul who, like the Hebrew scriptures, never mentions Hell at all.

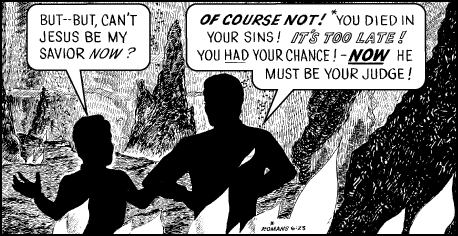

The much later so-called Gospel of Paul — like the so-called “Gospels” of Peter and Nicodemas — is obsessed with Hell, weaving a pseudo-Christian underworld out of Greek and Roman stories, dirty jokes and scatological humor. All of these pseudo-Gospels of Hell were, in their day, very popular. They were never seriously considered for inclusion in the Christian canon, yet most Christians had read them, or heard them, and the portrait of Hell they created has endured long after the books themselves were forgotten. That portrait today remains, in a sense, canonical for many believers who seem certain that it’s actually somehow biblical.

Alas, however, we seem to have done away with the scatological humor. Fart jokes are a recurring theme in Turner’s history and, particularly in medieval times, played a loud role in the popularity of the stories of Hell that came to shape our doctrine of Hell. The capering devils of medieval festivals were all about the fart jokes. In mystery plays, the actors portraying these fiends would sometimes set off fireworks attached to the seat of their pants. Pause to consider the safety and reliability of medieval explosives. This was a highly courageous act for such a low joke. Dante’s epic Inferno swept away and replaced much of the folklore of Hell that preceded him, creating a new standard of infernal lore. But to his great credit, the master poet retained the fart jokes.

I do not believe in a “literal” Hell in large part because I have not been able to find the alleged biblical literature literally teaching such a literal thing. But I am not trying here to persuade those who do believe in a literal Hell to change their minds. Here, instead, I am simply inviting them to look at Turner’s history as an aid to peeling away the layers of extrabiblical images and ideas that have accumulated and reshaped what we think of today when we hear that word “Hell.”

Close your eyes and say the word aloud. Hell. Do you think that what comes to mind for you is the same as what Jesus’ hearers understood when he spoke the word gehenna? What do you suppose they did understand when they heard that word? Whatever it was, whatever it could have been, it could not possibly have included all that has been added to the word since — from Dante, Milton, “Nicodemas,” Tundal and the rest.

Turner’s book is an inviting and entertaining map of the journey from there to here — from whatever it was that Jesus meant by gehenna to what we now imagine when we hear the word “Hell.” As such, it can also serve as a helpful guide for those trying to find their way back.