W. Scott Poole on “Praying to the Zombie Jesus: The Spirituality of Horror”

You might assume that all of this zombie Jesus talk exists on the level of simplistic parody, barbs hurled at Christianity by its less-than-cultured despisers. You would be wrong. Zombie Jesus has provoked some serious spiritual and existential reflection.

Laura Larson’s “The Business of Making Monsters” follows the same trajectory as Poole’s Monsters in America and arrives at a similar conclusion regarding our monstrous treatment of marginal people. (Poole got there with a bit less academic jargon, though.)

Laura Larson’s “The Business of Making Monsters” follows the same trajectory as Poole’s Monsters in America and arrives at a similar conclusion regarding our monstrous treatment of marginal people. (Poole got there with a bit less academic jargon, though.)

Some horror movies feature mad scientists. Others feature crazed occultists invoking strange magical rituals. Both of these things can be found in real life: “11 Ridiculous, Strange, And Terrifying Gay Conversion Therapy Methods For ‘Curing’ Homosexuality.”

Susannah Clements on “Why Are We So Attracted to Vampires?”

Clements has a book coming out with Brazos Press on the vampire myth: The Vampire Defanged: How the Embodiment of Evil Became a Romantic Hero. From a first glance, her understanding of Vampires and Crosses doesn’t seem to correspond with mine.

“Southern Baptist zombies“: Matthew Johnson argues that, for Southern Baptists, Mormons fall in the uncanny valley.

The whole point of the fundamentalist takeover of the SBC beginning in 1979 was to spark a “resurgence” in the life of the convention. Their theory was that taking over the Southern Baptist Convention in the name of biblical inerrancy and fundamentalist doctrinal purity would pave the way for an explosion in church growth and missions giving. Thirty years later, they continue to argue amongst themselves as church attendance continues to fall. Giving to their Cooperative Program for missions and ministry continues to decrease. The SBC has such an image problem they are considering a name change.

By contrast, Mormons out-Southern Baptist the Southern Baptists by almost any measure. Their children all serve as missionaries and their numbers are growing. Mormons generally have a reputation of being socially conservative, nice people with good family values. What’s more, many Mormon converts were previously Southern Baptist.

Isn’t this simply a version of the basic plot of any zombie movie? They are trying to turn us into them.

From the viewpoint of many Southern Baptists, Mormons are Southern Baptist zombies. Mormons hold the same family values as Southern Baptists. They talk about Jesus like Southern Baptists. They send out missionaries like Southern Baptists. They baptize people like Southern Baptists. But they believe the wrong things about Jesus, God and the Bible. For many members of the SBC, Mormons’ foreign/familiarity leaves them with the same creepy feeling we all get when we watch a George Romero movie.

Mormons are beating the Southern Baptists by the SBC’s own measures of success. The worst part is that Mormons are succeeding while holding theological tenets that Southern Baptists believe are anything but orthodox.

I just finished Poole’s Satan in America: The Devil We Know, in which Ozzy Osbourne keeps popping up as a favorite American monster — the object of fear and condemnation from cardinals and televangelists. Poole notes that, “Osbourne was never especially dark at all if his musical themes, rather than his persona, are used as a guide.”

The passage of time, and years of seeing Ozzy in the role of sit-com dad on his reality show, seem to be bringing more people around to that realization. Maybe you’ve seen this cute TV commercial for the Honda Pilot. It features a large family on a road trip who suddenly begin an impromptu-seeming a cappella rendition of “Crazy Train.” It’s quite charming, and utterly innocuous.

That’s kind of startling when you think about how Ozzy Osbourne was perceived back in 1980 when that song was first released. He was widely denounced as Satan’s minion and a corrupter of youth. He was the opposite of family friendly and a routine target for moral crusaders who campaigned to have his records labeled or banned or burned.

If you watch the extended version of that Honda ad, with these cute little kids singing the G-rated lyrics to “Crazy Train,” it’s hard to remember what all the fuss was about: “Maybe it’s not too late / To learn how to love / And forget how to hate.”

In context, those lyrics from “Crazy Train” were about the Cold War threat of mutually assured destruction. But more generally, they’re good advice as a response to those in “the business of making monsters.”

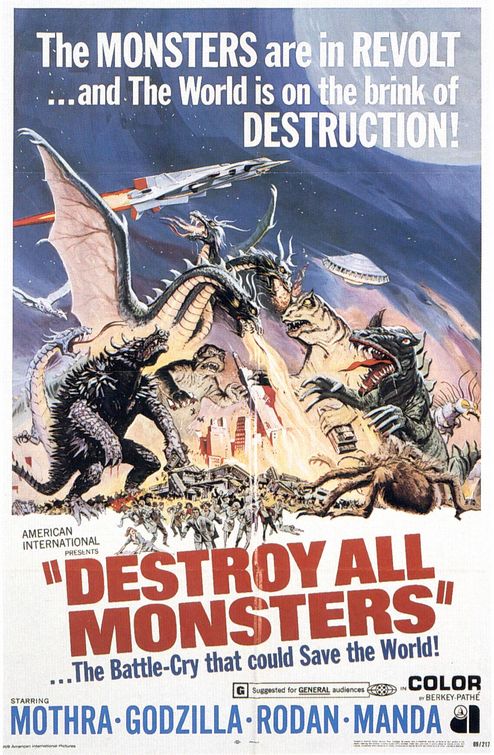

(Image above pinched from Cinefantastique, which has this appreciation of the film.)