Tribulation Force, pp. 443-445

After crushing insurrectionists in several locations with deadly force, the “potentate” of the one-world government addresses the world via radio:

“Loyal citizens of the Global Community,” came the voice of Carpathia, “I come to you today with a broken heart, unable to tell you even from where I speak. For more than a year we have worked to draw this Global Community together under a banner of peace and harmony. Today, unfortunately, we have been reminded again that there are still those among us who would pull us apart.”

Here again we encounter the all-sheep-are-wolves problem. I fairly sure that we’re meant to be appalled by this talk of “peace and harmony” from the man who just obliterated Washington, D.C. And I’m guessing that the next paragraph is meant to underscore Nicolae’s hypocrisy:

“It is no secret that I am, always have been, and always will be, a pacifist. I do not believe in war. I do not believe in weaponry. I do not believe in bloodshed. On the other hand, I feel responsible for you, my brother or my sister in this global village.”

In any other book, I’d be certain that this was meant as a heavy-handed display of that hypocrisy. But hypocrisy is only possible when the principle being violated is a legitimate one, and in the world of Left Behind it has been firmly established that there is no such thing as pacifism. We can’t read this as a criticism of Nicolae’s phony pacifism, because in the universe of these books, all pacifists are phonies.

I call this the all-sheep-are-wolves problem because that seems to describe how the authors arrived at this conclusion. The Antichrist, they believe, will rise to power “under a banner of peace and harmony,” but he will actually be a wolf in sheep’s clothing, using such talk to disguise his true purpose of global tyranny. Thus, for students of Tim LaHaye’s school of “Bible prophecy,” any leader who speaks of peace and harmony is a potential Antichrist. LaHaye urges his disciples to follow his example by presuming that anyone who speaks in such terms should be presumed guilty until proven innocent — proof of innocence, in this case, coming only when the person in question dies without having created a one-world government and declaring himself the Antichrist. Barring such proof, treat every apparent sheep as a wolf.

Thus after more than 800 pages of the authors insisting that pacifism is always a sham and an illusion, we can’t really be disillusioned by Nicolae’s sham pacifism.

Nicolae babbles on for another half a page before concluding with a final sentence that’s legitimately chilling:

“Above all, do not fear. Live in confidence that no threat to global tranquility will be tolerated, and no enemy of peace will survive.”

That last bit is creepy, in part, because it’s familiar. It’s the kill-all-the-bad-people strategy for peace — which is to say a recipe for endless total war.

Nicolae’s statement is followed by another report from the same “CNN/GCN correspondent.” This is the poor guy who was sent to report from the smoldering ruins of Washington, D.C., and is now anchoring the broadcast from his remote location:

“This late word: Anti-Global Community militia forces have threatened nuclear war on New York City, primarily Kennedy International Airport. Civilians are fleeing the area and causing one of the worst pedestrian and auto traffic jams in that city’s history. Peacekeeping forces say they have the ability and technology to intercept missiles but are worried about residual damage to outlying areas.”

Very little of that makes any sense at all, but I am glad he managed to work the traffic angle in again.

This insurrection, you’ll recall, is being coordinated by former President Fitzhugh with the assistance of patriotic “East Coast militias” (?). Why would Fitzhugh want to nuke New York City? The insurrection’s initial strike, one would think, would want to be something to rouse the larger population to rally against the OWG. Killing 10 million or so civilians doesn’t seem like the shrewdest approach to persuading others to join your struggle.

Or maybe this is all sheer propaganda — the plan to nuke New York just being a nasty lie invented by Nicolae to rouse sentiment against the insurrection. (It wouldn’t be the first time a leader has tried to consolidate unchecked power by demagoguing over an impending enemy attack on New York.)

And why the airport? Is that just because the Very Special Plane usually flown by the Very Special Pilot is headed there?

And what does Jerry Jenkins mean by “outlying areas”?

Jenkins ideas regarding that last question may be answered in the following paragraph, in which the same on-the-scene reporter brings us this news from overseas:

“And now this from London: A 100-megaton bomb has destroyed Heathrow Airport, and radiation fallout threatens the populace for miles. …”

OK. It seems Jenkins doesn’t quite appreciate the scale of the damage the bomb he’s describing would do. Via this blog, I learn of Carlos Labs’ Ground Zero mapplet, which allows us to visualize just how large the scope of the destruction would, in fact, be, from “A 100-megaton bomb” on Heathrow Airport.

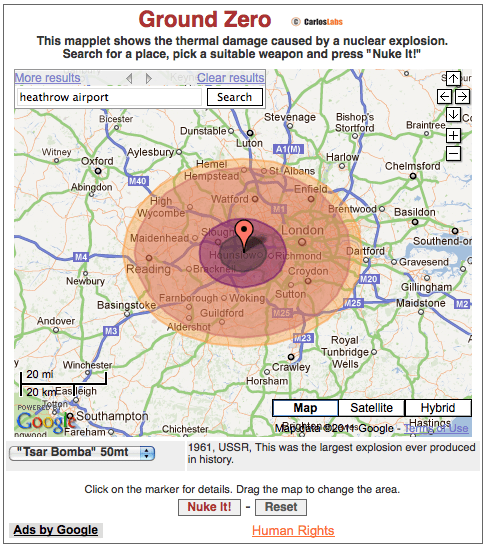

Or close to it, anyway. Here’s a look at what the range of the destruction would be from the Soviet “Tsar Bomba” — that was only a 50-megaton bomb, but it’s the biggest bomb ever tested. Keep in mind that Jenkins’ bomb would be twice as large:

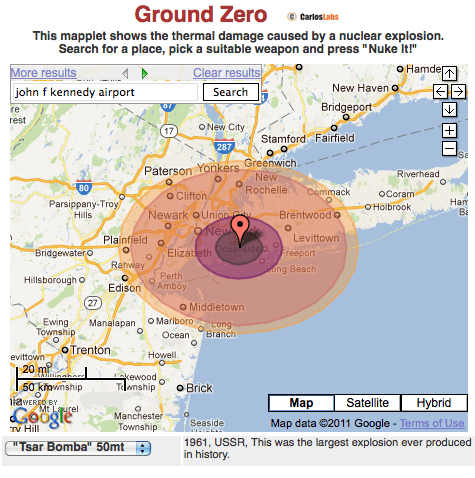

And here’s a look at a similar explosion at JFK airport.

Note that the “outlying areas” would be places like Trenton and Atlantic City:

I’m guessing those circles, indicating the range of total destruction, are quite a bit bigger than Jenkins was thinking.

“And now this from London: A 100-megaton bomb has destroyed Heathrow Airport, and radiation fallout threatens the populace for miles. The bomb was apparently dropped by peacekeeping forces after contraband Egyptian and British fighter-bombers were discovered rallying from a closed military airstrip near Heathrow. The warships, which have all been shot from the sky, were reportedly nuclear-equipped and en route to Baghdad and New Babylon.”

“It’s the end of the world,” Chloe whispered. “God help us.”

Her appropriate response is quickly forgotten as the car-pooling Tribulation Force presses on through the second-seal traffic jam in search of some way to get to Bruce at the hospital.

“Maybe we should just try to get to New Hope,” Amanda suggested.

“Not till we check on Bruce,” Rayford said. …

And Jenkins whisks us along, with the remaining pages of the book attempting to first build up readers’ suspense over Bruce’s fate and then have us mourn his death.

He doesn’t want us to give a second thought to the obliteration of London, but how can we not be concerned about that great city in which there are more than 8 million people, and also many animals?

It’s impossible to read this glib, passing reference to the destruction of London without thinking back to the miraculous protection of Israel from a similar nuclear attack early in the first book. The contrast between those two incidents confronts us with the matter of theodicy in the Left Behind universe.

“Theodicy” refers to the problem of evil. Briefly, if there is a God who is all-good and all-powerful, then why is there suffering, pain, evil and death? To paraphrase my favorite protest sign, why has this all-powerful God allowed stuff to get all fussed-up and bullstuff? (The poetry of that sign defies translation into family friendly terms.)

Christian theologians have a variety of responses to the problem of evil (none of which is terribly satisfactory, I’m afraid). But those responses are all geared toward this world, not to the world of Left Behind, which introduces a huge and hugely important difference: direct and explicit divine intervention on a massive scale.

We spent a great deal of time discussing the absurdity of the way the anti-nuclear miracle in the first book seems not to have changed anyone’s opinions on the existence of God. (One would think that the destruction of the entire Russian nuclear arsenal by an all-but-visible Hand of God might be a factor in considering that question.) But we haven’t considered what such an explicit act of divine intervention would mean with regard to the problem of evil.

The anti-nuclear miracle sets a precedent, indicating that neither human choice nor the physical laws of the universe in any way constrain God from intervening to prevent suffering. That miracle turns every other instance — every occasion on which God does not miraculously intervene — into an instance of deliberate divine non-intervention.

In other words, why did God protect Jerusalem, but not London (home to nearly a quarter million Jews)? Intervention in the first case entails divine complicity in the second.

The authors don’t address this because they’re not really interested in the problem of evil. As far as they’re concerned, that problem is solved. Suffering, evil and death, they say, are all deserved. They subscribe to a variation of that hyper-Calvinist theodicy which holds that all humans, everywhere, are indistinguishably and infinitely loathsome in the sight of a holy God. (Rachel Held Evans calls this “pond-scum theology.”)

This isn’t really a solution to the all-good/all-powerful dilemma. It dodges that question by redefining God’s “goodness” as something wholly other than what we humans understand as good — something that actually, from our human perspective, appears monstrous.

So I find pond-scum theology to be blasphemous even in its most consistent form, but it’s even worse here in the Left Behind series, where the authors embrace this hyper-Calvinist theodicy, but not hyper-Calvinist soteriology. They want to say, in other words, that the unredeemed deserve perdition while the saved — the real, true Christians like their heroes — deserve salvation.

This just gets more explicit and more ugly as the series progresses. In today’s section, the authors’ God refuses to protect London from destruction, but in the volumes ahead, God takes a more active role in raining fiery death down upon the cities of the world. In the volumes to come, the God of these books acts directly as the author of evil and the source of suffering. And the authors will never pause to consider what that suggests about their God’s character.

In Tim LaHaye’s favorite book of the Bible, Revelation, a heavenly chorus repeatedly interrupts the narrative to sing a hymn of praise: “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain.” In that hymn, the worthiness of God is located in God’s sacrificial rejection of power. LaHaye’s take on Revelation alters that hymn of praise into something more like “worthy is the God who slays.” That relocates God’s worthiness. For LaHaye, God is not “worthy” because God is good or loving, but rather because God is powerful.

That doesn’t just raise questions about the character of God, it raises questions about the character of the authors. It hints that the authors and their protagonists have chosen to be on God’s side mainly because it’s the winning side.