For the past five years, I’ve been part of a big Catholic family, even before I married into it.

Due to lease logistics, I moved in with my future father-in-law for the five months before my wedding. Three of us lived in that house: me, Pop and my wife’s Uncle Joe, a retired priest. We joked that it was our bachelor pad — the widower, the celibate and the fiancé.

I stayed in a room that had once belonged to another priest — a man who was such a close friend of the family that my wife grew up calling him “Uncle Father.” He spoke at the funeral of her mother and then, three years later, he spoke at Pop’s funeral too.

After the ‘vixen and I got married, Pop sold his house and moved out here to live with us in Chester County, while Uncle Joe moved in with his brother.

Our girls went through confirmation out here. That turns out to be a pretty big deal, with the whole family — aunts and uncles on both the Irish and the Italian sides — in attendance. I even picked up Aunt Bern at the convent so she could be there.

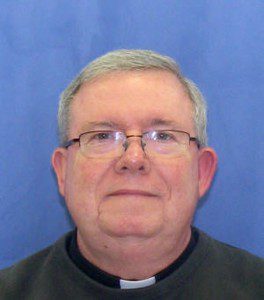

As a lifelong Baptist, I’d never been to a confirmation before, but it reminded me of my own baptism. There was no dunking, of course, and with dozens of children in every class it was a much larger and somewhat younger crowd, but the gist of it was still familiar, even with all the additional pomp and circumstance. Between my two daughters and two of their cousins, I attended four confirmation services in as many years. At each of them, the children were quizzed on their catechism by a revered veteran priest out here — a monsignor actually.

You may have heard of him. He’s famous now — even got profiled in Rolling Stone. And he was on the news last night here in Philly.

Monsignor William Lynn, as Sabrina Rubin Ederly wrote for Rolling Stone, was:

… a high-ranking official in Philadelphia’s archdiocese. Lynn, who reported directly to the cardinal, was the trusted custodian of a trove of documents known in the church as the “Secret Archives files.” The files prove what many have long suspected: that officials in the upper echelons of the church not only tolerated the widespread sexual abuse of children by priests but conspired to hide the crimes and silence the victims. Lynn is accused of having been the archdiocese’s sex-abuse fixer, the man who covered up for its priests.

Lynn himself is not accused of abusing children. His role was to keep the abusers’ secrets secret. He is accused of covering up and hushing up the scandal on behalf of the archdiocese — protecting the institution by endangering its children. When a priest was discovered to be abusing children, prosecutors say, it was Lynn who saw to it that they were quietly reassigned elsewhere. He shuffled them off to a new location — and not to someplace where they’d be away from children, that might have looked suspicious:

Bill Lynn understood that his mission, above all, was to preserve the reputation of the church. The unspoken rule was clear: Never call the police. Not long after his promotion, Lynn and a colleague held a meeting with Rev. Michael McCarthy, who had been accused of sexually abusing boys, informing the priest of the fate that Cardinal Bevilacqua had approved: McCarthy would be reassigned to a “distant” parish “so that the profile can be as low as possible and not attract attention from the complainant.” Lynn dutifully filed his memo of the meeting in the Secret Archives, where it would sit for the next decade.

Over the 12 years that he held the job of secretary of the clergy, Lynn mastered the art of damage control. With his fellow priests, Lynn was unfailingly sympathetic; in a meeting with one distraught pastor who had just admitted to abusing boys, Lynn comforted the clergyman by suggesting that his 11-year-old victim had “seduced” him. With victims, Lynn was smooth and reassuring, promising to take their allegations seriously while doing nothing to punish their abusers. Kathy Jordan, who told Lynn in 2002 that she had been assaulted by a priest as a student at a Catholic high school, recalls how he assured her that the offender would no longer be allowed to work as a pastor. Years later, while reading the priest’s obituary, Jordan says it became clear to her that her abuser had, in fact, remained a priest, serving Mass in Maryland. “I came to realize that by having this friendly, confiding way, Lynn had neutralized me,” she says. “He handled me brilliantly.”

… In 2005, the grand jury released its 418-page report, which stands as the most blistering and comprehensive account ever issued on the church’s institutional cover-up of sexual abuse. It named 63 priests who, despite credible accusations of abuse, had been hidden under the direction of Cardinal Bevilacqua and his predecessor, Cardinal Krol. It also gave numerous examples of Lynn covering up crimes at the bidding of his boss.

In the case of Rev. Stanley Gana, accused of “countless” child molestations, Lynn spent months ruthlessly investigating the personal life of one of the priest’s victims, whom Gana had allegedly begun raping at age 13. Lynn later helpfully explained to the victim that the priest slept with women as well as children. “You see,” he said, “he’s not a pure pedophile” – which was why Gana remained in the ministry with the cardinal’s blessing.

Lynn’s devotion to the institution above all else shaped his initial defense. Prosecutors had hoped that serious charges and the threat of serious prison time would get Lynn to roll over, implicating the officials whose orders he was carrying out. But Lynn was a loyal company man, willing to sacrifice himself to protect the archdiocese, its secrets, and its culpability. He was willing to serve as the Wee-Bey for the church, taking the blame and the prison time on himself and thereby protecting others. Eberly describes the courtroom scene from last year:

“You have been charged. You could go to jail,” [Judge Renée Cardwell] Hughes says gravely. “It may be in your best interest to provide testimony that is adverse to the archdiocese of Philadelphia, the organization that’s paying your lawyers. You understand that’s a conflict of interest?”

“Yes,” Lynn replies.

The judge massages her temples and grimaces, as though she can’t believe what she’s hearing. For 30 minutes straight, she hammers home the point: Do you understand there may come a time that the questioning of archdiocese officials could put you in conflict with your own attorney? Do you understand that you may be approached by the DA offering you a plea deal, in exchange for testimony against the archdiocese? Do you realize that is a conflict of interest for your lawyers?

“Yes, Your Honor,” Lynn continues to insist cheerfully.

But that changed last month when Lynn’s former boss died. Once Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua was dead, the archdiocese’s defense team decided that a dead man made an even better scapegoat than a living loyal soldier. Bevilacqua had denied any involvement in or knowledge of Lynn’s work covering up the rape and abuse of dozens of children. But now Lynn’s attorneys are willing to implicate the late cardinal and to paint him as the lone bad apple on whom all the blame should rest.

The Philadelphia Inquirer’s John P. Martin reports:

Cardinal Anthony J. Bevilacqua ordered aides to shred a 1994 memo that identified 35 Archdiocese of Philadelphia priests suspected of sexually abusing children, according to a new court filing.

The order, outlined in a handwritten note locked away for years at the archdiocese’s Center City offices, was disclosed Friday by lawyers for Msgr. William J. Lynn, the former church administrator facing trial next month.

… “Msgr. Lynn was completely unaware of this act of obstruction,” attorneys Jeffrey Lindy and Thomas Bergstrom wrote.

Their motion asks Common Pleas Court Judge M. Teresa Sarmina to dismiss the conspiracy and endangerment charges against Lynn, or to bar prosecutors from introducing Bevilacqua’s videotaped testimony at trial.

That would be the testimony in which the cardinal perjured himself, swearing that he knew nothing of the list of abusive priests that he had personally ordered his underlings to shred. Martin writes that “The revelation is likely to further cloud Bevilacqua’s complicated legacy in the handling of clergy sex abuse.”

No. It clarifies Bevilacqua’s legacy. He was a liar. He lied to preserve church assets and he lied because the preservation of those assets — money, money, money — was a far greater priority for him than the protection of children or justice and healing for victims. And for this lying and this single-minded devotion to money, Bevilacqua was “elevated” to the position of cardinal.

Let’s be clear here: shredding those documents could never keep the church’s crimes hidden. The crimes Bevilacqua and Lynn worked so hard to conceal had been witnessed by too many people — by the victims themselves. The document-shredding and perjury were simply an attempt to buy time until the statute of limitations was exhausted, shielding the accused priests from criminal prosecution and thus making civil litigation more difficult and, for the archdiocese, less costly. It wasn’t just the statute of limitations they were waiting for either. The victims of such horrific childhood abuse are often prone to self-destructive behavior or even to self-destruction. The longer the cardinal and his lackey could delay their day of reckoning, the fewer victims might be left to testify against them. And the more time the church would have to “investigate the personal lives” and dig up dirt on those survivors brave enough to speak up.

Lynn and his defense team had another bad day in court yesterday:

City prosecutors yesterday continued to pile on the allegations that a former high-ranking official of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia facilitated the sexual abuse of church children by repeatedly looking the other way when confronted with jaw-dropping crimes of predator priests.

“Time and time and time again, they lie to victims because they are not concerned about the victims; they are just concerned about the almighty dollar and mother Church,” Chief of Special Investigations Patrick Blessington said of the Archdiocese, which once employed the four defendants who are to stand trial in March.

“What they’re talking about is the archdiocese as a whole,” protested Lynn’s attorney Jeffrey Lindy. He’s right. The criminal conspiracy goes far beyond his client. And “the archdiocese as a whole” should be investigated under RICO as a criminal enterprise.

Oh, and there was one more list of names. Beyond the 63 priests listed in the original grand jury report and the 35 named in the memo Bevilacqua tried to destroy, there was another list of 21 priests suspended “because of allegations of sexual abuse or other inappropriate behavior with minors.”

One of the priests on that list was Uncle Father.

You remember him — he’s the man who twice briefly lived with my wife’s family when she was a kid. They gave him a place to stay when he was between parish assignments. This was years before Lynn’s tenure as secretary of the clergy for the diocese. There was a different fixer handling things back then.

That last list, like the grand jury report and the charges against Lynn, didn’t become public until after Pop died. I’m glad of that. I’m glad that he was spared that bit of ugly truth about why the friend he trusted was between assignments. It was, he had been told, just a routine situation — nothing out of the ordinary. And that much, I guess, was true.