I don’t believe in ghosts because, if there were such a thing, then I think the following would be a true story. As far as I know, it is not. …

It’s not widely discussed. Those who have witnessed it firsthand are, for obvious reasons, reluctant to talk about it. You’ll never see them publicly recounting their tales in front of the cameras and the microphones. These aren’t stories they are eager to tell.

But one hears whispers, rumors, stories told by the friends of friends. And those whispers, rumors and stories are too numerous and too eerily similar to be dismissed.

Something is happening. Something, it seems, happens every Friday the 13th, just before midnight.

The stories begin right around the turn of the 20th century, with the earliest reference I can find coming from August of 1897.

The stories begin right around the turn of the 20th century, with the earliest reference I can find coming from August of 1897.

Capt. B.F. Auld of the Baltimore Police Department received a strange and surprising invitation to dinner at the home of Supreme Court Justice Henry Billings Brown. The two men had never met, and Capt. Auld never fully understood the reason for the invitation, but after what he described as their “distressing” conversation, he guessed it was because he had, two years earlier, been present at the funeral of Frederick Douglass.

“You saw him, then?” the justice asked him, with what Auld described as a “fearful” look. “And you are certain, without doubt, that he is, indeed, dead? You are certain?”

Auld never learned what prompted this feverish interrogation, and after firmly assuring Brown of all that he had seen at the great man’s funeral, the justice abruptly dropped the subject and the captain finished his meal in silence.

From later stories we can, I think, guess with some confidence what really lay behind that curious interview.

Consider, for example, the odd tale Charlie Chaplin told photographer Richard Avedon. The great genius (Chaplin), recalled a party at which a drunken D.W. Griffith had held him spellbound with his account of a terrifying “nightmare” he’d had in January of 1917. “‘I hear the mournful wail of millions,’ he told me,” Griffith had said, becoming manic and shaking visibly. “And he made me hear them too!” The next day, Chaplin said, the famed director told him it was just a clumsy, drunken jest, and begged him never to mention it again.

The details of Chaplin’s anecdote echo in another story told by the late Rep. Philip Campbell. As chairman of the House Committee on Rules, Campbell conducted hearings in October of 1921 on the violence of the revived Ku Klux Klan. The terror group’s leader, “Col.” Joe Simmons, was called before Congress. You can read accounts of his testimony, but most of those accounts neglect to mention that he also met with Campbell privately following those hearings and told the congressman of a disturbing “vision” he’d had two months before. Simmons’ vision was remarkably similar to Griffith’s nightmare — including even that exact phrase, “the mournful wail of millions.”

But Simmons was certain it had been more than a bad dream. “He was there,” he told Campbell, “Physically there beside my bed.”

I’ve unearthed dozens of similar stories, and hints of stories, and rumors of hints of stories. Seeking them out began as a hobby of sorts and later grew into an obsession.

My entrance into this strange world began with a friend from seminary whose identity I will protect here out of respect for his privacy. His father had been a prominent white southern preacher and a popular religious author, but he’s remembered today mainly for having been a fierce defender of segregation in the 1960s. I made some awkward joke about the similarity of my friend’s name with that of this notorious figure and only then realized, embarrassed, that this infamous man was his father.

It was then that my friend shared with me his father’s story — his whole story, which included more than just the horrifying headlines the man had earned during the Civil Rights era. I hadn’t realized that the old preacher had later repented of his segregationist views, abruptly resigning from the pulpit of his large church, becoming a teacher and, eventually, spending his last years as the humble pastor of a tiny, multiracial congregation in a small storefront church.

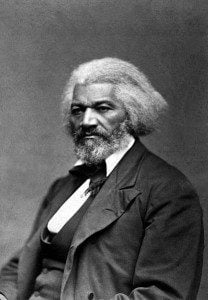

My friend traces that transformation back to a day when he, as a child, was sitting at the kitchen table doing schoolwork. He’d been assigned a book report by his grade-school teacher, an old Quaker who was all too aware of his father’s views. And so when his father came into the kitchen, he saw that book — a children’s adaptation of Douglass’ Narrative — sitting on the table. And there, on the cover, was the same famous portrait of Douglass I’ve included here.

“What is this?” my friend’s father had said, seizing the book before he could respond. “It’s him! How did you …?”

And then, after frantically examining the book for a moment, he just stood there, trembling and staring at the picture on the cover. My friend said it frightened him to realize, for the first time, that his father could be frightened too.

“He’s … he was a real person?” his father was muttering. “He was real. It was … it really …” He fled the house, taking the book with him, and didn’t return for hours. After that, my friend says, his father was a changed man.

My friend’s version of this story, I should note, is much more dramatic — and far more detailed — than his father’s own account. I tracked down a water-damaged copy of his long out-of-print memoir, From Galling Chains Set Free, in which he describes that day, suggesting he was simply angry that his son’s teachers were assigning such reading material. He rushed off to read the book seeking, as he put it, “ammunition for the next school board meeting,” but then, unexpectedly, found it moving and persuasive. He mentions it was the first time he’d ever seen a picture of Douglass, but he never describes that moment of horror-struck recognition after seeing the book’s cover and never explains what it might have meant.

So which account was more accurate? Did it really happen the way my friend remembered it? I’ll just say this: That chapter of his father’s memoir is titled, “An Unexpected Visitor From the Past.”

What I’ve pieced together from all these stories sounds unbelievable, and I certainly cannot prove any of it. But there are more things in heaven and earth than I can prove.

All I can tell you is what I believe. And what I believe is this: Somewhere in America, just before midnight on every Friday the 13th, the ghost of Frederick Douglass appears at the bedside of some racist wretch.

On some occasions, it seems, he stands silently, glowering with blazing eyes. That’s how then-Sen. Lyndon Johnson described him. (Although, once again, the description comes to us only very indirectly, through a confidant of Betty Ford’s. Ford said Lady Bird Johnson told her of an “awful dream” that left her husband shaken and unsettled throughout the final months of 1959. She used those exact words, “blazing eyes,” which we can only assume was a phrase her husband himself had used.)

Sometimes, apparently, Douglass speaks, condemning the one he is visiting with all the famed eloquence and devastating wit of America’s greatest orator and prophet. (In divorce papers, Cornelia Wallace described her husband George as having, the previous spring, spent “three days with his nose in the dictionary,” looking up words “he’d heard in a dream.”)

And sometimes, on rare occasions, it seems that Douglass’ spirit possesses the same great physical strength that the man himself had in life. At least a couple of stories suggest that these visitations have sometimes involved a serious, corporeal ass-kicking. In 1913, Ty Cobb missed several games in late June due to vague injuries he never explained to manager Hughie Jennings. Fifty years later, on Sunday, Sept. 15, Byron de la Beckwith showed up in church with badly bruised ribs and a greenish-yellow shiner nearly closing his left eye. No one quite believed his story about falling down the cellar stairs, and from that day until his death in 2001, it was rumored that the warped old man never slept a wink on the night of any Friday the 13th.

All of this raises many questions for which I have no answer. Why Friday the 13th? Why were these particular people visited rather than others? Why were some of them transformed while others seemed, if anything, even more set in their ways following the visitation?

And who’s next?

All I know is this: Later this month, on Monday the 16th, somewhere in America a man will arrive at work looking clammy and pale. He may be a politician, a preacher, a TV host or radio personality. He may be a famous leader, a celebrity, or someone whose name most of us would never recognize.

“Are you alright?” his friends and colleagues will ask, “You don’t look well.”

And he’ll insist, a bit defensively, that yes, yes, he’s fine, just fine. Just a little tired. Rough weekend. Trouble sleeping.