RJS at Jesus Creed reports on the recent Theology of Celebration Workshop hosted by the Biologos Foundation, reported on by Christianity Today as a gathering of “evangelical evolutionists.” As RJS notes, that’s an unsatisfying label, but I suppose it works as a reminder that there are, in fact, evangelical theologians who do not deny evolution.

RJS writes:

[CT’s Tim] Stafford suggests that the most sobering point in the meeting was the report by David Kinnaman of Barna Research that more than half of Protestant pastors in the US support young-earth creationism or lean strongly toward that position. The poll includes the entire range of Protestants, so we can safely assume that well over half of evangelical pastors lean toward the young earth view.

The most sobering point for me though, was not this particular finding (which was not unexpected), but the realization that the vast majority of this “more than half” of evangelical pastors, more than three-quarters of them, believe that they understand both the theological issues and the scientific issues involved in the creation/evolution discussion very well.

RJS goes on to discuss the enormous challenge of explaining even basic science to a large category of people who: A) don’t understand or want to understand it; and B) think they already understand it just fine. I don’t share all of the suggestions RJS makes for meeting this challenge, but many of them are good and necessary, if daunting.

My biggest reservation is with this part of the post:

We need scientists; those who can explain the science carefully and clearly for a lay audience. Here I find Dennis Venema’s articles on the BioLogos site to be excellent examples and provide a valuable resource.

My response to this suggestion is “What do you mean ‘we,’ kemosabe?”

For a scientist to be able to “explain the science carefully and clearly for a lay audience” is a rare gift, but it’s a big world and there are a lot of excellent science writers.

For a scientist to be able to “explain the science carefully and clearly for a lay audience” is a rare gift, but it’s a big world and there are a lot of excellent science writers.

The problem isn’t that we lack scientists, the problem is that we are defining “we” in a way that excludes everyone who isn’t already a member of our evangelical tribe.

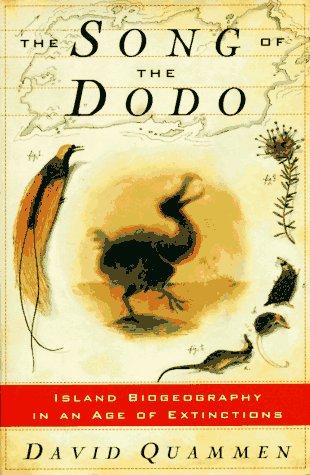

Whenever the subject of careful and clear science writing for a lay audience comes up, I leap at the chance to recommend one of my favorite books — David Quammen’s The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction. It’s fascinating, absorbing and utterly accessible to those of us who haven’t spent years studying biology. Quammen offers a lively tour of the insights of Darwin and Wallace and all that we’ve learned since, all while also introducing the reader to some of the strangest and most intriguing places and creatures on the planet. It’s a terrific book.

But if “we” decide that “we” can only read books written by “us,” then Quammen’s book doesn’t count. Nor can we read anything by Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking, Richard Dawkins, Janna Levin, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Jared Diamond, Mary Roach, Stephen Jay Gould, Steve Jones, Phil Plait …

Maybe Annie Dillard counts, but it’s a bit of a stretch to claim her as one of us.

It’s no good saying “we need scientists … who can explain the science carefully and clearly for a lay audience” and then to turn around and exclude nearly all of the best writers who can do just that because we cannot claim them as members of our tribe.

That leaves us with precious little to draw from except the sort of books the BioLogos Foundation recommends. Many of the books on that page may be excellent (I’ve not read most of them), but many are also one step removed from actual science writing. They’re about science, but not necessarily on science. I appreciate the need for books intended specifically for evangelical readers — books that can serve to give those readers permission, in a sense, to learn about science. But the universe of good, popular science writing is much bigger than this small bookshelf.

And ultimately it has to include not just books reassuring evangelicals that faith and science aren’t in conflict, but also the books that such reassurance enables one to go on to read. I’m a big fan of Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, but if we convinced every American evangelical to read Noll’s book without them going on to read all the vast universe of books he laments that they’re not reading, then we wouldn’t have really accomplished anything. We might have raised awareness of the scandal, but we wouldn’t have corrected it.

If evangelicals are refusing to learn from Quammen and Sagan and the other writers mentioned above, then the solution is not to seek out or create a new, evangelical Quammen or Sagan. That’s the approach that gave us the wretched “contemporary Christian music” industry. CCS would like prove just as awful as most CCM.

That analogy helps point us to a better way forward. The problem with CCM isn’t just that the artists creating this parochial music for the rest of the tribe need to be better at their craft. The problem is that they’re creating parochial music for the tribe and that the members of that tribe regard themselves primarily as members of that tribe, refusing to listen (or pretending not to listen) to the wider universe of good music made by and for the “outsiders” of the rest of the world. American evangelicals don’t need better tribal music. We need to stop approaching music through the lens of tribalism.

Likewise, American evangelicals don’t need better tribal scientists. We need to stop approaching science through the lens of tribalism.

So to every one of those half-of-all evangelical pastors now trapped by the confusion of young-earth creationism, my suggestion is simply this: Go read The Song of the Dodo by David Quammen. You’ll thank me later. It’s a terrific book.