RJS at Jesus Creed reminds us that anyone who wants to know what the Bible says about creation can’t just stick with Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 (or with some half-baked attempt to harmonize Genesis 1 and Genesis 2).

Citing William P. Brown’s book The Seven Pillars of Creation, RJS notes that there are many more creation passages in the Hebrew scriptures, including Job 38-41, Psalm 104, Proverbs 8:22-31, Ecclesiastes 1:2-11 and 12:1-7, and bits of Isaiah 40-55.

That section of Job in particular, RJS says, offers quite a bit to balance out the conclusions one might be tempted to leap to based on an exclusive reliance on a “literal” reading of Genesis.

I’ve made this case before regarding Job and Psalm 104, but hadn’t ever considered those other passages Brown cites as “creation” texts. That seems like a bit of a stretch for those passages from Ecclesiastes, but it’s a really interesting stretch.

* * * * * * * * *

Ed Brayton’s rant against the “Evolution Article Template” expresses his frustration with the way new finds that fill out our understanding of the fossil record are always trumpeted as “missing links.”

The “missing link” idea has become a mug’s game. It’s a trap, based on Zeno’s dichotomy paradox — a way for science-denying “skeptics” to pretend that the fossil record can never be meaningful.

They’re like Thelonius Monk, demanding “the notes between the notes.” There’s a link missing, they say, between C and D. Well, here’s C# — the missing link between C and D. Not good enough, they say, there’s still a link missing between C and C# — the piano is still incomplete and meaningless. And viewed this way it can never be regarded as complete or meaningful. It’s a mug’s game.

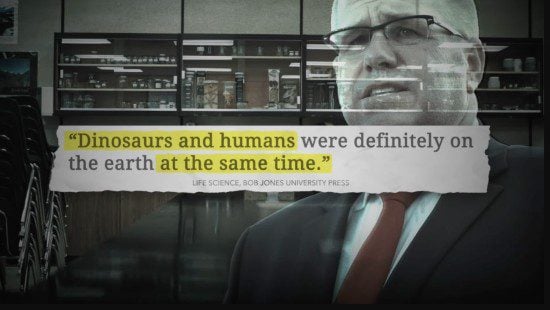

I learned this trick from earnest creationists who did not themselves realize that it was a trick — a sleight-of-hand device designed to avoid knowledge or to deny it. It’s one of many such devices young-earth creationists employ in order to live in this world without ever looking at it.

* * * * * * * * *

The Sensuous Curmudgeon takes a look at what Answers in Genesis has to say about the “Post-Flood Dispersal of Animals.”

That’s a more inclusive term for what I’ve referred to as “The Long March of the Koalas.”

(Basically, if you’re a Genesis-Is-Journalism illiteralist, then you believe the Earth is only 6,000 years old, and that every creature on the planet is descended from those on a historical Noah’s Ark. Mount Ararat is in eastern Turkey or Kurdistan, so this requires young-earth creationists to explain how Australian kangaroos, koalas and echidnae managed to trek across all of Asia and then swim or paddle their way to their island home.)

* * * * * * * * *

Remember the mantis shrimp — the lobsterlike sea creature we talked about recently, with sixteen cones and a perception of color we can’t even imagine?

Ed Yong reports on another remarkable fact about these colorful creatures: “How mantis shrimps deliver armor-shattering punches without breaking their fists.”

Mantis shrimps — neither mantises nor shrimps — are pugilistic relatives of crabs and lobsters. [David] Kisailus says that they look like “heavily armoured caterpillars.” They kill other animals with a pair of hinged arms held under their heads. In the “spearer” species, the arms end in an impaling spike, while the “smashers” wield crushing clubs.

The smashers deliver the fastest punch of any animal. As the club unfurls, its acceleration is 10,000 times greater than gravity. Moving through water, it reaches a top speed of 50 miles per hour. It creates a pressure wave that boils the water in front of it, creating flashes of light (shrimpoluminescene — no, really) and immensely destructive bubbles. The club reaches its target in just three thousandths of a second, and strikes with the force of a rifle bullet.

Read the whole, fascinating, link-filled post to learn why mantis shrimps are able to punch so hard without shattering their own fists.

For me, this is one more reason to re-read the immensely reassuring words from Sidney Perkowitz’s Hollywood Science:

Imagine you make an ant twice as big while keeping its bodily constitution the same. According to the mathematics of scaling, the bigger insect would weigh eight times more, but its legs would have strengthened only by a factor of four. The legs would carry twice the relative load for which nature had designed them. Every further increase in size would make the weight to strength ratio that much worse. At some point, the ant couldn’t even stand up.

I meditate on that passage every time I watch the Shelob’s Lair scenes in The Lord of the Rings. Giant invertebrates aren’t scientifically possible. Phew.

Still, though, an Attack of the Giant Mantis Shrimp B-movie might be kind of awesome. SyFy call your office.