Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist, pp. 35-48

The Tribulation Force, like every band of heroes, needs a tech whiz.

That stock character is familiar because he or she brings a vital skill set — vital both for the team and for the writer. Somebody needs to be able to provide the know-how that can carry the team past any technological obstacle or carry the writer past any awkward gap in the plot. Every team needs someone who can step up and reverse the tachyon pulse, hack into the database, or MacGyver together the tracking device that leads the hero to the villain’s lair.

That’s true even here in the alternate universe of technology of the Left Behind series. Despite these books’ “not-so-distant future” setting, the authors struggle to incorporate even the technology that already existed at a popular consumer level when these books were written (this one in 1997). That’s partly because Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins seem a bit technologically backwards, but it’s also because their story and their setting derives so much from the mythology created by Hal Lindsey and other popular “Bible prophecy” writers of the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, for example, the Web doesn’t matter much in this world because, even by 1997, it didn’t matter much to LaHaye and Jenkins, and also because they were cribbing so much from The Late Great Planet Earth, which was written before the Web existed.

There’s also the problem of these authors’ general habit of mind when it comes to thinking about the future. Science fiction writers can project or imagine technological and cultural developments to envision future worlds. But if you asked Tim LaHaye about the world of the future, all he could tell you is there won’t be one.

We thus encounter weirdly anachronistic and ineffective passages of tech-ish stuff that all tends to involve 1980s-style technology like printers and phone systems. Even more glaring are the constant reminders of the absence of 1990s technology in these books — whether that’s Global Weekly’s print-only publishing platforms or the way Bruce’s “struggles” with the temptation of pornography involved print-edition magazines on physical newsstands.

Here in the third book, Jenkins makes a bid for a technological upgrade. It arrives in the person of Donny Moore. We first meet him, of course, on the telephone:

“Donny,” Buck said. “I need your advice, and I need it right away.”

“Mr. Williams, sir,” came Donny’s characteristic staccato delivery, “advice is my middle name. And as you know, I work at home, so I can come to you or you can come to me and we can talk whenever you want.”

I tried, and mostly failed, to read that with a “staccato delivery.” And then I began to fear that this was intended as some kind of awkward ethnic cue about the character. And that, in turn, led me to fear that the disparity between “Donny” and “Mr. Williams, sir” might be another, even more awkward such cue. Let’s hope not.

Maybe Donny just calls Buck “Mr. Williams, sir” because he’s really young. Or maybe everyone at New Hope calls Buck “Mr. Williams,” just as they all seem required to address Rayford as “Captain Steele.”

Donny, it turns out, is the church’s tech guy. In this series, of course, that doesn’t primarily mean computers, but telephones. How else would we expect Jerry Jenkins to establish Donny’s tech-whiz credentials?

“I’ll be right over, Mr. Williams, but could you tell me something first? Did Loretta have the phones off the hook there for a while?”

“Yes, I believe she did. She didn’t have answers for people who were calling about Pastor Bruce. With nothing to tell people, she just turned off the phones.”

“That’s a relief,” Donny said. “I just got her set up with a new system a few weeks ago, so I hope nothing was wrong.”

This is made more explicit several pages later:

Donny Moore proved more of a talker than Buck appreciated, but he decided feigning interest was a small price for the man’s expertise. “So, you’re a phone systems guy, but you sell computers –”

“On the side, right, yes sir. Just about double my income that way. Got a trunk full of catalogs, you know.”

“I’d like to see those,” Buck said.

Donny grinned. “I thought you might.”

I should be used to this by now, but it’s still always startling to see our heroes act like such pricks without the authors even realizing they’re being pricks. Here we’re told that Buck is a patronizing jerk, “feigning interest” in this guy just so he can use him for what he needs, but this is presented as though it’s something admirable — evidence that Buck is a take-charge, no-nonsense guy.

I’m thus sort of pleased to imagine that what we’re seeing here is also a glimpse of how Jenkins himself purchased his own computer back in 1997 — from a catalog pulled out of the trunk of some fast-talking guy’s car. I’d like to think the guy milked him for every penny.

Donny seems more hustler than hacker here, displaying more sales-savvy than tech-savvy.

“Excuse me a moment, Donny,” Buck said. “Did you hear that printer quit?”

“I sure did. It just stopped now. It’s either out of paper, out of ink, or done with whatever it was doing. I sold that machine to Bruce, you know. Top of the line. Prints regular paper, continuous feed — whatever you need.”

And yes, that did just happen. In the middle of the scene in which Jenkins is trying to introduce his idea of high-tech wizardry, he pauses to tell us that our heroes have succeeded in printing out the contents of Bruce’s hard drive because they think that reproducing a 5,000-page hard copy is the best, fastest and easiest way to disseminate that information as widely as possible. In 1997.

“When’s Bruce gonna be back here?” Buck heard Donny ask from the other room.

Buck tells him the sad news, and Donny is heartbroken.

It’s hard not to read the page that follows, in which Buck tries to comfort him, without suspecting that Buck is merely feigning compassion. That suspicion is deepened when Buck seems to pivot into exploiting Donny’s grief in order to haggle down the “price for the man’s expertise”:

“Donny,” Buck said gravely, “you have an opportunity here to do something for God, and it’s the greatest memorial tribute you could ever give to Bruce Barnes. … Whatever profit you build in or don’t build in is up to you. I’m just telling you that I need five of the absolute best, top-of-the-line computers …”

And here again we see that Donny is not the tech whiz the Tribulation Force needs. He’s just a salesman. It’s as though instead of going to Q for his equipment, James Bond went to some guy who knows Q and says he can maybe buy some stuff from him at a competitive price.

In any case, Donny Moore shouldn’t be in this story at all. The technological acumen — or tech-purchasing acumen — he brings should have been supplied by someone else, by someone already part of the team.

This role should have gone to Chloe.

Mrs. Williams needs to bring something to the table other than her service as designated damsel in distress. And she was a Stanford student, after all, so it wouldn’t have been a stretch to have written in some old school connections who could have hooked Buck up with all the high-powered clandestine computers he wants.

Chloe really ought to have evolved into a super-hacker by now. The Tribulation Force desperately needs a good hacker, and Chloe needs some way to contribute, and her back-story ought to more than qualify her for the role.

But that didn’t happen. The possibility probably did not even occur to the authors. First because Chloe is a woman. And second because the authors don’t seem to know anything at all about computers or the Internet. Yes, this book was written in 1997, but I think LaHaye and Jenkins missed War Games (1983) and Max Headroom (1985) and Sneakers (1992) and Hackers and The Net (both 1995). So even though the young female super-hacker was already a cliché, I doubt L&J had any clue that such a character was possible.

Buck goes on to list what he needs in his five computers:

“… small and compact as they can be, but with as much power and memory and speed and communications abilities as you can wire into them. … I want a computer with virtually no limitations. I want to be able to take it anywhere, keep it reasonably concealed, store everything I want on it, and most of all, be able to connect with anyone anywhere without the transmission being traced.”

“Well, sir, I can put together something for you like those computers that scientists use in the jungle or in the desert when there’s no place to plug in or hook up to.”

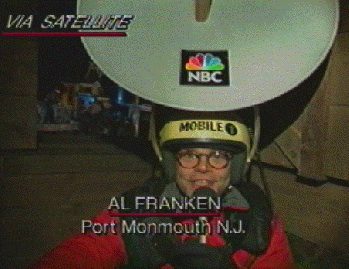

“Yeah,” Buck said. “Some of our reporters use those in remote areas. What do they have, built-in satellite dishes?”

Donny explains that the technical term is “something like that.” And then he delights Buck with the prospect of another feature he can provide with these computers:

“Video conferencing.”

“You mean I can see the person I’m talking to while I’m talking to him?”

“Yes, if he has the same technology on his machine.”

And that right there is the pay-off — the reason for this whole interlude with Donny Moore. It’s not that Buck Williams really needs computers, but that Jerry Jenkins really wants his characters to have video-phones.

It will be several chapters before Buck actually receives his new computers, but even then it seems that these devices are much more for Jenkins’ use than for his. They serve the narrative convenience of the writer more than any needs of his characters or his plot.

That’s even clearer in the opening pages of the next chapter, in which we return to Rayford Steele. He’s touring the shiny new “Condor 216” with its designer, his former boss, Earl Halliday.

“I put something in here just for you,” Earl tells him:

“Just look at this,” Earl said. He pointed to the button that allowed the captain to speak to the passengers.

“Captain’s intercom,” Rayford said. “So what?”

“Reach under the seat with your left hand and run your fingers along the side edge of the bottom of your chair,” Earl said.

“I feel a button.”

That button, as Earl then demonstrates, is for a super-secret eavesdropping device he super-secretly installed throughout the plane. Every speaker on the plane, he says, “is also a transmitter. … I wired it in such a way that it’s undetectable.”

So with the press of a secret button, Rayford will now be able to eavesdrop on every word Nicolae Carpathia says on the airplane. More importantly, Jerry Jenkins will now be able to narrate every word Carpathia says on the plane, even when Rayford is not in the room.

This was Earl’s job in this book, just as it was Donny’s job to supply Buck and his friends with video-phones. They existed, as characters, simply to supply the pretext for a couple of narrative conveniences.

Having finished those appointed tasks, they will both, in short order, be killed off. Jenkins, apparently, was only feigning interest in Earl and Donny because that was the price he had to pay for their expertise.