Joe Hanson shared this quote from Michio Kaku: “Physicists are made of atoms. A physicist is an attempt by an atom to understand itself.”

And vorjack shared this from Phil Hellenes:

It’s like the universe screams in your face, “Do you know what I am? How grand I am? What are you, compared to me?”

And when you know enough science, you can just smile up at the universe and reply, “Dude, I AM you.”

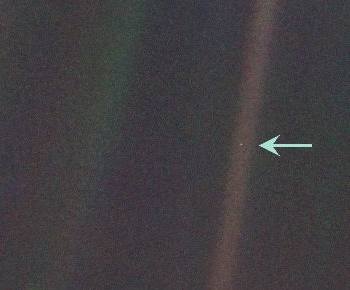

Vorjack says, “I like the sentiment, but we’re only a tiny part of the universe.” And thus it’s a stretch to “[equate] ourselves with the universe because ‘we are all star dust’ or something similar.”

I agree. Each of us is only a tiny part of the universe. A tiny, tiny part.

But undeniably a part of it nonetheless.

And that, it seems to me, has to be an essential consideration for considering the “Big Question” recently posed by the John Templeton Foundation: “Does the Universe Have a Purpose?”

Neal deGrasse Tyson’s response to this question — “I’m not sure” — seems to have gone viral. That’s deservedly so, since it’s his usual Sagan-esque mix of science and near-poetry (and has already been transformed into another terrific NdGT-narrated YouTube video).

Tyson emphasizes how very, very tiny we are against the incomprehensible vastness of space and time. This is science, but it reads like one of the monologues spoken by the character God in the book of Job:

If you are religious, you might declare that the purpose of life is to serve God. But if you’re one of the 100 billion bacteria living and working in a single centimeter of our lower intestine (rivaling, by the way, the total number of humans who have ever been born) you would give an entirely different answer. You might instead say that the purpose of human life is to provide you with a dark, but idyllic, anaerobic habitat of fecal matter.

Tyson concludes:

So in the absence of human hubris, and after we filter out the delusional assessments it promotes within us, the universe looks more and more random. Whenever events that are purported to occur in our best interest are as numerous as other events that would just as soon kill us, then intent is hard, if not impossible, to assert. So while I cannot claim to know for sure whether or not the universe has a purpose, the case against it is strong, and visible to anyone who sees the universe as it is rather than as they wish it to be.

The problem there, as Kaku and Helles remind us above, is that our wishes for how the universe ought to be are part of the universe. A tiny, tiny part of it, perhaps, but a part of it nonetheless.

We have a say in this.

We cannot consider the question “Does the Universe Have a Purpose?” without considering the sub-question “Do I Have a Purpose?” or even the sub-question to that, “Do I Want to Have a Purpose?”

Answering “Yes” to that third question means answering “Yes” to the second. And that means — even if only in a very tiny, tiny way — answering “Yes” to the first.

Consider Jane Goodall’s response to Templeton’s question. Maybe all that talk of wonder and beauty and spirit is just her wishful thinking. But even so, as she argues there, the wishful thinking of Jane Goodall is also a part of the universe and thus must also be at least a part of what we consider when we ask if the universe has a purpose.

I’m not really disagreeing with Tyson here, just trying to approach the question differently than his essentially Thomistic take. He echoes scholastic arguments when he says:

To assert that the universe has a purpose implies the universe has intent. And intent implies a desired outcome. But who would do the desiring?

Many theologians have posed that question in just that way, of course answering, “God — God does the desiring, and God supplies the intent.” I believe that’s true, but I can’t supply any more evidence that it is than the God-character supplied to Job.

As Nancey Murphy said in her response to Templeton’s question: “Nothing can be known of any plan for the future perfection of the world or the human condition.”

So let’s try another answer to this question from Aquinas and Tyson: “Who would do the desiring?”

How about us? You and me — we can do the desiring.

That’s actually a terrific word for what we are capable of doing as incomprehensibly tiny parts of the universe. We can’t ensure any outcome, or impose our intent on the universe. But we can desire a purposeful outcome.

“The arc of the moral universe is long,” Dr. King said, “but it bends toward justice.” That’s a statement of faith, not of science. It’s a statement about the universe as we wish it to be rather than as it is — “random,” with “events that are purported to occur in our best interest … as numerous as other events that would just as soon kill us all.”

But our desiring, our wishing it to be, is also part of what is. A tiny, tiny part, perhaps, but there it is.

That’s why as much as I like the responses from Tyson, Goodall and Murphy, my favorite of all the responses from Templeton’s conversation comes from Elie Wiesel. Does the universe have a purpose?

“I hope so,” Wiesel said. “And if it doesn’t, it’s up to us to give it one.”

Does the universe have a purpose? Do you have a purpose? Do you want to have a purpose?

Three forms of the same question. And my answer is the same as those of Goodall, Tyson and Wiesel: Certainly, I’m not sure, I hope so.