James McGrath responds to Jim West’s attempt to play Baptist Enforcer, pointing out that Baptists, by definition, do not and cannot have enforcers.

Pretty much the only way to break the rules as a Baptist is to try to enforce them on others.

McGrath writes:

Jim West has taken it upon himself to try to define away the status of the First Baptist Church of Seattle as a Baptist church.

Jim considers their stance on same-sex marriage and their holding of ceremonies marrying people of the same gender to be incompatible with Baptist identity.

But ironically, apart from believer’s baptism, one of the most fundamental and characteristic tenets of the Baptists is soul freedom – the right and duty of individual believers, and communities of believers, to follow the dictates of their consciences, without compulsion from authoritarian structures.

So congratulations to Jim West for having – rather ironically – defined himself out of Baptist identity by thinking that he can dictate to other Baptists how to follow their consciences or their understanding of Scripture.

Yes. Although I’d quibble with one point there — I don’t think the idea of soul freedom is something “apart from believer’s baptism.” The two things are inseparable, and soul freedom comes first. Believer’s baptism is an expression of soul freedom.

The other unavoidable expression of soul freedom, of course, is the separation of church and state. That’s why I also want to commend McGrath’s recent smackdown of Mike Huckabee. It’s astonishing that Huckabee — a Baptist minister — is claiming that God is judging America for not establishing a sectarian state religion in our schools.

Huckabee is about as “Baptist” as Cardinal Richelieu.

* * * * * * * * *

Also here on Patheos, Scot McKnight continues his discussion of Edward Fudge’s Hell: A Final Word:

Some contend that endless punishment for temporal sin is “intuitively and irreconcilably inconsistent with fundamental justice and morality.”

The quote there is from Fudge, but I’m among the some who contend this as well.

What McKnight wants to contend with in his discussion is the response to that objection, particularly the response that tends to come from Reformed theologians:

Some contend right back that such a theological claim for that reason is arrogance , unsubmissive to God’s Word and rooting theology in our own moral perceptions. OK, I get that … but …

… anyone who claims humans don’t know justice and injustice, at some intuitive level, are standing on morally dangerous turf.

McKnight shares Fudge’s three-point response to this idea that God’s justice might be so utterly different from “our own moral perceptions.” Head over there to read that. But here’s the end of McKnight’s post, in which he poses two questions that hint at his own conclusions:

Can we comprehend justice well enough to know when something is just or unjust? Is the accusation, rooted in our intuitive senses of justice, that eternal punishment does not square with temporal sin a good argument?

The answer to both questions is “Yes.”

I appreciate the Reformed contention that we finite, fallible humans are not capable of grasping perfect justice. But that insight becomes a blindness when it gets twisted into the idea that we are utterly incapable of distinguishing justice from injustice, or that we are wholly mistaken when we perceive something as more or less just.

I appreciate the Reformed contention that we finite, fallible humans are not capable of grasping perfect justice. But that insight becomes a blindness when it gets twisted into the idea that we are utterly incapable of distinguishing justice from injustice, or that we are wholly mistaken when we perceive something as more or less just.

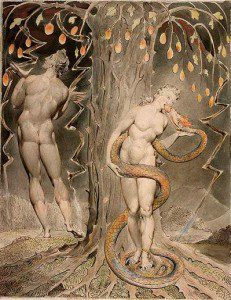

We are imperfect and limited, and our best approximation of and understanding of justice will never be perfect or complete. But those who want to argue that our fallen nature makes us incapable of the knowledge of good and evil really need to re-read that story in Genesis.

God’s idea of justice surely transcends our own. And just as surely it cannot violate our own.

Eternal torment for temporal sin is monstrous. The claim that God is so transcendently good that God’s goodness appears monstrous to us is, frankly, perverse.