So earlier this week I got into a back-and-forth on the old necessary/sufficient distinction. That was still kicking around in my mind when I overheard some TV commercial or infomercial in which the spokesman said this exact phrase: “How many times have you heard someone say.”

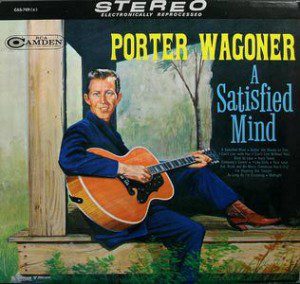

And thus, because of the way my brain works, I had an old Porter Wagoner song stuck in my head for the rest of the day. (Wagoner was the first to have a hit with “Satisfied Mind,” and I thought he wrote it until I looked it up and learned it was written by Red Hayes and Jack Rhodes.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkKOnS8J5GMI love that song — the Blind Boys of Alabama version above, or the Dylan version from Saved, or the Johnny Cash version, or the Mahalia Jackson version.

But it occurs to me that this song offers the same confusion that marked my earlier argument. Or, rather, the same confusion that prevented my earlier exchange from even rising to the status of an argument.

Here’s the first stanza of that song:

How many times have you heard someone say

If I had his money I could do things my way

But little they know that it’s so hard to find

One rich man in ten with a satisfied mind

The singer and “someone” seem to be talking past each other without either really addressing what the other is saying. “If I had his money I could do things my way,” is, mainly, a complaint due to the lack of money. The singer’s reply warns that money is no guarantee of happiness.

We could paraphrase this exchange as something like this:

We could paraphrase this exchange as something like this:

SOMEONE: Money is necessary.

SINGER: Money is not sufficient.

They’re both right. The singer seems to think he’s correcting “someone,” with that “but little they know.” Yet his assertion doesn’t contradict what the poor someone is saying. Both statements can be — and both are — true.

This exact conversation occurs and recurs a lot, often among people who imagine they’re disagreeing. It’s actually the very conversation we should expect to hear between a poor person and a rich one. “Money is necessary,” is the truth that every poor person knows. Likewise, “Money is not sufficient,” is the truth that every rich person knows. It’s also very easy for poor people, because they know money is necessary, to imagine that it might also be sufficient. And it’s very easy for rich people, because they know money is not sufficient, to forget that it is, nonetheless, utterly necessary.

Unfortunately, in most of the endless iterations of this conversation between rich and poor, none of this is expressed in these categories of necessary and sufficient, and so neither side may be able to hear or to learn what the other knows. Instead, the conversation goes something like this:

SOMEONE: Boy, life would be a lot easier if I had enough money.

SINGER: Money doesn’t guarantee an easy life.

They think they’re disagreeing when all along they’re actually both saying parts of the same thing: Money is necessary, but not sufficient. Put it that way, and both someone and singer can agree and move forward from there. But if we fail to see that this is what’s really being said, there can’t be any agreement or even any disagreement — just a lot of confused talking past one another.

For an example of what that sounds like, see every discussion of public school funding ever. Education is another place where the simple truth is that money is necessary, but not sufficient for decent outcomes. Yet every time anyone mentions the need for funding, the response is always that funding is no guarantee of success. “You can’t just throw money at the problem!” That’s not the rebuttal those folks imagine it is. It’s not even relevant enough to qualify as a disagreement.

We don’t usually get tripped up by such confusion when we’re talking about things other than money. If someone says, “You can’t make chocolate milk without the chocolate,” no one will angrily reply that you can’t just throw chocolate at the problem, or that chocolate is not sufficient for chocolate milk. We only seem to get that confused and angry when it’s about money.

Or about sex — which was the subject of that back-and-forth I mentioned up there at the beginning of this post. I had been arguing that consent is a necessary component of any sexual ethics, which met with a sneering response along the lines of “Oh, as long as it’s between two consenting adults then you say anything goes!”

The simple truth that consent is necessary, but not sufficient, for sexual ethics is as likely to be grasped by a puritanical religious person as the simple truth that money is necessary, but not sufficient, is to be grasped by a rich person.

The distinction is not complicated, or unusual. But it tends not to be understood by those who have a stake in not understanding it.