As an evangelical Christian, I can appreciate the legal pretense of an Orthodox Jewish eruv.

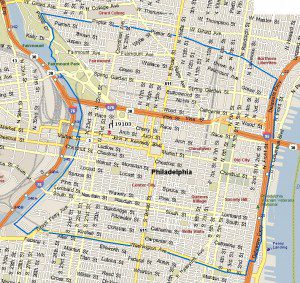

I had never heard of such a thing until reading Michael Chabon’s brilliant alternate-history detective novel The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. Yet it turns out that I’d spent most of the 1990s living within the sprawling Lower Merion eruv, and much of the next decade commuting into and out of and through the huge eruvin of Center City and University City. (The blue line on the map in this post denotes Philly’s Center City eruv.)

Here’s a helpful description of an eruv from the Jewish Press last month:

Jewish law prohibits carrying an object from a private domain to a public domain (or vice versa) or within a public domain on the Sabbath. … The creation of an eruv establishes, where possible, an extended private domain in which such carrying is permissible.

The rules regarding “carrying” between “domains” on the Sabbath are complicated, but deadly serious. Those rules are so extensive that it would be easy to violate them unwittingly or unintentionally. They also forbid some things that would seem necessary for anyone traveling to or from services on the Sabbath. Say you have severe asthma or extreme allergies and need to carry an inhaler or an EpiPen with you at all times. The law forbids you to carry such things from one domain (your home) to another (the street leading to your local synagogue) on the Sabbath. An eruv technically encompasses the entire area within a single domain, turning whole neigborhoods or cities into one “courtyard,” thus permitting carrying within the eruv without violating the law.

The idea shows an enormous, immersive respect for biblical law while simultaneously showing an enthusiastic willingness to elude that same law through ingeniously creative means. In a sense, the elaborate nature of the law-evading construct becomes an expression of reverence for the very law it evades. Technically, the law forbids you from carrying from point A to point B. The eruv creates a legal fiction whereby technically you can. The lawyerliness of the latter technicality pays tribute to the deep sincerity of the former.

The idea shows an enormous, immersive respect for biblical law while simultaneously showing an enthusiastic willingness to elude that same law through ingeniously creative means. In a sense, the elaborate nature of the law-evading construct becomes an expression of reverence for the very law it evades. Technically, the law forbids you from carrying from point A to point B. The eruv creates a legal fiction whereby technically you can. The lawyerliness of the latter technicality pays tribute to the deep sincerity of the former.

In Chabon’s novel, the community’s dependence on the eruv and its keepers enables crafty, crooked men to wield power over others by making them the arbiters of who is or is not within the bounds of the law. They become the gatekeepers of others’ righteousness.

Like I said, this all seems terribly familiar to those of us who have lived within the subculture of white evangelicalism. So much so that it’s tempting to abandon the original point of this post and just go galloping off into exploring the eruv as a metaphor for white evangelicalism in America.

But here’s the key thing: The boundaries of an eruv have to be physical, tangible and real. They’re nearly invisible, even if you know where to look and you know what you’re looking for. Walk along Poplar Street in Philadelphia and look very carefully and you may spot the boundaries of the blue line on the map here — a length of wire, a bit of thin pipe affixed to a utility pole. The lines these boundaries draw enclose a fictive space, but the lines themselves must be real.

There are, of course, many, many rules about the rules that allow one to abide by the rules. (Familiar, all too familiar.)

Ari Kohen draws our attention to a battle over a proposed eruv in Westhampton Village, New York:

The eruv would consist of about 60 10-to-15-foot-long, five-eighths-of-an-inch-wide PVC strips affixed to utility poles, and painted to blend in with them. They would be difficult to see, and would be shorter than the poles themselves.

That’s how these things work. If you don’t know it’s there, you’d never know it was there. You can’t see it, and unless you’re an Orthodox Jew it doesn’t affect your life at all in any way.

And yet many of the residents of Westhampton Village — including the mayor — want to prevent the Orthodox community from constructing its eruv. They offer two reasons for this. The first is an attempt at a principled-sounding argument. The second is an accidental admission of simple discrimination (which is why Kohen’s post is titled, “Oops, You Said the Quiet Part Out Loud“).

Let’s address the supposedly principled argument first. Out in the Hamptons, they’re arguing that an eruv somehow constitutes an establishment of religion in violation of the First Amendment:

In 2012, the Quogue board of trustees ruled that constructing an eruv “would very likely constitute a violation of the establishment clause” of the Constitution, and denied the application. Southhampton and Westhampton Village have not made a formal ruling, but Mr. Teller, the mayor, said he agreed with that reasoning.

“It’s about the separation of church and state,” he said.

That’s ridiculous. It ignores the existence of eruvin in communities all over the United States, none of which have been challenged, let alone ruled against, as any sort of religious establishment. Because they are not any sort of religious establishment — the state is not involved, and they do not affect anyone except the members of the Orthodox community. They are not noticed by anyone except the members of the Orthodox community.

If the city were being asked to fund the construction of the eruv, that would be a violation of the Establishment Clause. If the existence of the eruv meant that suddenly every resident had to begin abiding by the Orthodox Jewish restrictions against carrying on the Sabbath, then that would clearly be unconstitutional. But the town is not being asked to pay for any of this, only to allow its existence. And none of the non-Orthodox residents of the town will be asked or required even to acknowledge its presence.

So what’s really behind the opposition to the Westhampton Village eruv? The ugly truth seems to be that because it would make life easier for Orthodox Jewish residents, it might attract Orthodox Jewish residents, and the people of Westhampton Village don’t want those kind of people around. The law might not allow Westhampton to prohibit Orthodox Jews from building a synagogue, but perhaps the law can be manipulated to prevent them from being able to get to that synagogue. And if so maybe they’ll all just go away.

It’s discrimination, plain and simple. It’s no different from the anti-Islamic bigotry opposing the “Ground-Zero mosque” (which was neither a mosque, nor very near Ground Zero) or opposing the mosque in Murfreesboro, Tenn.

That would be a harsh accusation to level against Mayor Teller and his constituents, but they’ve already confessed to it. As Kohen said, they unintentionally “said the quiet part out loud”:

Estelle Lubliner, another Jewish member of the anti-eruv group, said she feared that the eruv “will make more Orthodox people come in, and it’s not right to the history of these towns.”

“Why are they forcing the community to change?” she added.

… [M]any in Westhampton Village — a diverse mix of Catholics, Protestants and Jews — say they fear the prospect of more Orthodox Jews moving in if the eruv is constructed. The mayor, Conrad Teller, estimated that perhaps 90 to 95 percent of Westhampton Village is now against it. “It’s divisive,” he said. “I believe they think somebody’s trying to push something down their throats.”

Storekeepers on Main Street have voiced practical concerns, because Orthodox Jews traditionally don’t spend money on the Sabbath. “Retail is hard enough as it is,” said Anick Darbellay, sitting in her dress shop on Friday. “I don’t want to have to shut down on Saturdays. Have you been to the Five Towns?” she asked, referring to an Orthodox Jewish enclave in Nassau County. “That’s what happened there.”

That’s just straight-up We Don’t Want You Here. It’s explicit bigotry, explicitly stated.

Kohen comments:

It’s absolutely bizarre — and very sad — that, rather than attempting to learn something about those whose beliefs are different, the majority population immediately acted like there was some sort of terrible threat to their country and their way of life.

Yep, the majority population perceives that a minority constitutes “some sort of terrible threat to their country and their way of life,” and so they impose legal restrictions against that minority, all the while trumping up disingenuous arguments that such restrictions against the freedom of the minority are necessary to protect the “religious liberty” of the majority. The very existence of the minority, the majority says, is “divisive.”

The eruv is a legal fiction that allows Orthodox Jews to carry on the Sabbath. The “religious liberty” argument of the privileged majority is a legal fiction that allows them to impose their will on others while pretending they’re making a principled stand for freedom.

The former is benign and unobtrusive. The latter is not.