Here are some wise words from J.R. Daniel Kirk in 2011 on pastors and the Synoptic Problem:

It is your pastoral responsibility to help people recognize that the Bible we actually have, rather than the Bible of our imaginations, is the word of God.

If you don’t give your people a category for this kind of diverse Bible being the word of God, then you will create a false sense of connection between a supposedly uniform, univocal Bible and the Christian faith as such. So what happens when they go off to college and take a Bible class at State University? What happens when they get bored one Saturday and map out (or try, anyway) the last week of Jesus’ life in each of the four Gospels?

Uh oh.

That’s when they discover that the Bible isn’t what you led them to believe. And if that imagined Bible is necessary for believing what God has to say about Jesus and the Christian faith in general, then the latter are apt to crumble as well.

Make no mistake, there are tremendous pastoral issues at stake in affirming correctly what the Bible is. But one of the worst mistakes we can make, especially in a day and age where media will tell people the truth if we don’t, is to affirm a vision of a single-voiced scripture that fails to correspond to the text we have actually been given.

Anyone who grew up fundamentalist knows exactly what Kirk means when he talks about getting bored one Saturday and trying to map out the last week of Jesus’ life in each of the four Gospels. We know what he means because we did this.

I remember the first time I made such a chart. It was right after I got my telescope, so I think I was in about the third grade. I was reading everything about astronomy that I could get my hands on, including ambitiously tackling Ben Bova’s In Quest of Quasars — which was a bit beyond my little-kid reading level.

And as a good fundamentalist Baptist kid, I was also reading the Bible. I lay down on the floor with our gargantuan copy of Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance and looked up every passage that had anything to say about stars or space or the sun or the heavens declaring the glory of God. There’s some really lovely stuff in there, like 1 Corinthians 15:41: “There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars: for one star differeth from another star in glory.” (Bova used that verse as an epigraph before one of his chapters.)

And as a good fundamentalist Baptist kid, I was also reading the Bible. I lay down on the floor with our gargantuan copy of Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance and looked up every passage that had anything to say about stars or space or the sun or the heavens declaring the glory of God. There’s some really lovely stuff in there, like 1 Corinthians 15:41: “There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars: for one star differeth from another star in glory.” (Bova used that verse as an epigraph before one of his chapters.)

And that also led me to look more closely at the creation stories in the beginning of Genesis. The story in Genesis 1 was a bit confusing, with light being created three days before the sun and moon. (Light from where? Did such source-less light cast a shadow?) But I quickly forgot about that once I encountered the bigger puzzle: The story in Genesis 2 didn’t fit with the story in Genesis 1. Seven days turned into one. People were made before plants instead of plants before people.

I had been assured by preachers and Sunday school teachers that these stories could be “harmonized,” but I couldn’t make that work. I tried — I made a chart, tracing out the two stories in parallel, but the pieces just couldn’t be made to fit.

I had, as Kirk said, discovered that the Bible wasn’t what I had been led to believe.

That did not lead, at that time, to a crisis of faith in the Bible, but rather to a crisis of faith in my Sunday school teachers. It seemed obvious to me that anyone who read the first two chapters of Genesis would have to realize that the two stories couldn’t be harmonized. So I didn’t begin to doubt that the Bible was trustworthy, but I did begin to have serious doubts that my teachers had actually read it.

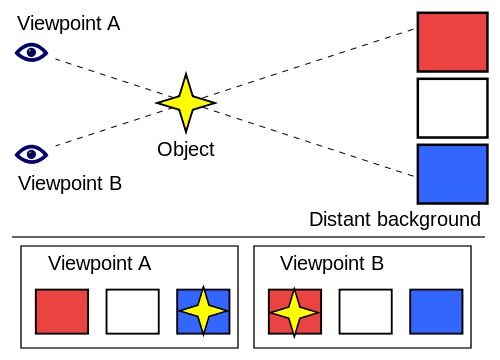

Instead of trying to harmonize those stories, I adapted a concept I had just learned from Mr. Bova and decided that these two incompatible stories offered something like a kind of parallax view of creation. That, in turn, led to a mutually perplexing conversation with a Sunday school teacher in which, for a moment, we both sat there, holding up an index finger while winking at each other with first one eye, then the other. He didn’t seem to appreciate my idea, but in fairness I don’t think I was explaining it very well.

That’s a relatively benign example of the kind of Pastor Fail that Kirk warns against. But the stakes are often much higher — particularly in churches that make biblical “inerrancy” an all-or-nothing, non-negotiable foundation of Christian faith. When that happens — when salvation and meaning and Jesus and God’s love are made contingent on the Bible being inerrant and wholly consistent in every particular — then people are being set up for a devastating crisis of faith that can only be avoided by not reading the Bible.

A recent Baptist Press story includes a puzzling account from Mike Licona about his students at Southern Evangelical Seminary catching their first glimpse of the crisis of faith awaiting them:

Licona recalled a student in a class he was teaching at Southern Evangelical Seminary who, with tears forming in her eyes, wanted to know whether there were indeed contradictions. A majority of the class, he said, raised their hands to indicate they were troubled by apparent contradictions. Then he realized it was something he should address.

I say this account is puzzling because Licona seems surprised by this. How is that possible? How had he managed to live and teach in the inerrantist Southern Baptist culture without having encountered this same question dozens of times before? How had he avoided asking those questions himself?

The next bit from the Baptist Press story is even stranger:

As he studied the Gospel accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, Licona began keeping a document of the differences he noticed. The document grew to 50 pages.

So here we have a man teaching in a seminary who seems never to have heard of the Synoptic Problem. How does that even happen?

I commend Licona for determinedly setting out to reinvent the wheel independently, but wouldn’t it have been easier just to, you know, go to the library and consult the shelf-after-shelf of volumes written about all of this?

I’m not saying that from an academic perspective, but from a pastoral one. Licona here is describing himself as being surprised by questions that every church youth group volunteer has faced year after year with every crop of kids.

We tell those kids to read the Bible and a few of them actually do. And some of them actually “get bored one Saturday and map out (or try, anyway) the last week of Jesus’ life in each of the four Gospels.”

And then they have questions. They notice the differences between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 and they ask about it. They notice the differences between the Synoptic Gospels and John and they ask about them. They notice the differences among the Synoptic Gospels and they ask about those. Some of the brighter and more ambitious Bible readers will even ask about some of the more esoteric bits gleaned from the not-always-compatible stories in the histories of the Hebrew scriptures.

And if you don’t know how to answer those questions, then you’ve got to do more than bluff around them, because any kid who reads 1 Chronicles on her own deserves a serious, honest response.

How is it that Licona hadn’t previously encountered those kids’ questions? How is it that he hadn’t previously asked them himself?

But as weird as it is to ponder Licona’s innocence about such questions, what’s even weirder is the claim that Dr. Al Mohler makes in this Baptist Press story.

Mohler doesn’t claim to be upset by Licona’s approach to the Synoptic Problem. Mohler claims to be upset that Licona acknowledges there is a Synoptic Problem. Mohler simply asserts that every detail of all four Gospels is completely consistent. The “Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy” says so, so it must be true — even if everyone who’s ever read all four Gospels knows this is ridiculous.

Mohler, in comments to Baptist Press Feb. 6, said, “It would be nonsense to affirm real contradictions in the Bible and then to affirm inerrancy.”

“Even Dr. Licona concedes that we ‘may lose some form of biblical inerrancy if there are contradictions in the Gospels.’ What you lose is inerrancy itself,” Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, said. “The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy clearly and rightly affirms ‘the unity and internal consistency of Scripture’ and denies that any argument for contradictions within the Bible is compatible with inerrancy. An actual contradiction is an error.”

… “The Christian faith rests on a comprehensive set of truth claims and doctrines,” Mohler said. “All of these are revealed in the Bible, and without the Bible we have no access to them.”

That leaves only two possibilities. The second, and more charitable of the two, is that Al Mohler has never read the Gospels. (The only other possibility is the one that won Burt Lancaster an Academy Award.)

What will happen if Al Mohler ever does read the Gospels? What will happen if he gets bored one Saturday and tries to map out the last week of Jesus’ life in each of them? What will happen when he confronts the fact that no amount of shoving, shaving, squinting and blurring can ever produce a seamless “harmonizing” of Matthew and Mark and Luke and John?

Will the whole house of cards come tumbling down? Or will he be able, at long last, to separate the Bible as it is from the elaborate construct he has built all around it?

Chaplain Mike takes a thoughtful look at this whole Mohler/Licona kerfuffle — including an excellent spit-take at Norman Geisler’s impossible-to-swallow statement that Licona has strayed from “the historic view of inerrancy.”

That’s a bit like saying someone has strayed from “the historic view of Lysenkoism.” No, wait, actually that’s exactly like saying that.

Chaplain Mike quotes from the original Internet Monk, Michael Spencer:

We need not claim that the Bible is “…a perfect compass. Or a perfect map. Or a perfect book. Because God is perfect. And if God said it, it must be perfect. It’s perfect. Really, really really perfect. Not just true. Not just a book that brings us Christ and the Gospel. Perfect. And if you don’t come out and walk around saying the Bible is perfect, then you reject the Bible.”

And then he adds: “My friends, our faith is not a Jenga game, dependent on blocks of post-Enlightenment logic being stacked just right so that they are in danger of collapsing if one of them is moved the slightest bit.”

The precarious Jenga tower of perfect consistency that Al Mohler has erected cannot survive an attentive reading of the Gospels. I wonder if Mohler could survive it himself.