(Content note: This post discusses sexual abuse and its defenders.)

We’ve discussed before the white evangelical preoccupation with having the proper “stance.”

That’s a favorite subcultural word — stance. “What’s your stance on inerrancy?” they’ll ask.

“Probably unacceptable to you,” I’ll answer, which is all they really wanted to know.

“What’s your stance on homosexuality?” they ask, and I try to answer while biting my tongue and wishing I could be fed straight lines like that one in settings where it was possible to make the most of them.

This obsession with policing the proper stance on various subjects is a symptom, I think, of a subculture in which orthopraxy has been almost completely abandoned. When orthodoxy is all that’s left, it’s not surprising that everyone should be incessantly interrogated as to the acceptability of their stances.

This obsession with policing the proper stance on various subjects is a symptom, I think, of a subculture in which orthopraxy has been almost completely abandoned. When orthodoxy is all that’s left, it’s not surprising that everyone should be incessantly interrogated as to the acceptability of their stances.

That’s troubling, given that Jesus did not say, “take this stance,” but rather “Follow me.” We’re supposed to be moving, not striking a pose.

Another problem with this whole stance business is revealed in the response we see from evangelical leaders to scandals involving the sexual abuse of children. Some of these responses have been awful, but I don’t think this is a result of anyone having the wrong stance regarding such abuse. I think pretty much everyone is agreed that the abuse of children is a horrific evil. We all have the same stance, and the proper one, when it comes to such things.

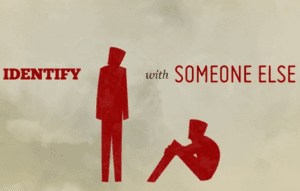

Yet it turns out that having the proper stance just doesn’t matter much. Our response to incidents of abuse turns out not to depend on having the right stance. It depends, instead, on who we choose to stand with.

Doing the right thing — i.e., doing good, loving — is almost always a matter of where we’re choosing to stand and of who we choose to stand beside much more than it is an abstract matter of the rectitude of our stance. This is why the Bible is so belabored and repetitive in its discussion of the weakest, the oppressed, the downtrodden, the least of these — those Nicholas Wolterstorff calls “the quartet of the vulnerable,” meaning “the widows, the orphans, the resident aliens, and the impoverished.”

Even when the Bible is laying out long lists of rules — especially then — it is reminding us that these rules are meant to place us at the side of those most vulnerable to, and most injured by, injustice. Remember that you were underdogs in Egypt.

Another way of saying this is that it is a matter of allegiance. When abuse occurs within an institution, it threatens that institution. If our primary allegiance is to that institution, then that is what we will defend. But if, instead, our primary allegiance is to the underdog, always and everywhere — which is to say, if our primary allegiance is to Christ — then we will act first and foremost to defend those harmed by the abuse, and to defend those potentially harmed by future abuse if the matter is not dealt with conclusively and openly.

This should not be complicated. It only becomes complicated if we make the mistake of imagining that the proper “stance” is more important than who we’re standing with.

We seem to make that mistake a lot, which is why Christians keep confusedly acting as though their primary allegiance is to the institution of the church — defending the institution at all costs, even if that means silencing or shaming the victims of abuse, or covering up for the predators who abused them.

This is why popular Reformed pastor/blogger Tim Challies face-planted in his attempt to respond to the systemic abuse and cover-up allegations against his friends at Sovereign Grace Ministries. Challies posted a response that reads like something disgraced former Catholic Archbishop Bernard Law might have written. It’s all about maintaining “unity” amid the “turbulence” and about preserving the institution and its reputation, since the wicked world is watching and “loves nothing more than to see Christians in disunity, accusing one another, fighting one another, making a mockery of the gospel that brings peace.” He treats the wounds carelessly, saying “‘Peace, peace’ when there is no peace.”

The problem with Challies’ response is not his “stance,” but that he’s standing in the wrong place, standing by the wrong people, standing on the wrong side. His allegiance is cast with the institution, not with the vulnerable.

Challies comes from a religious tradition that emphatically rejects any teaching role for women. As T.F. Charlton notes, that patriarchal perspective means that it’s more difficult for him to perceive the danger and injustice of abuse.

Challies’ refusal to recognize women as teachers is also unfortunate because his post on Sovereign Grace Ministries prompted several excellent, wise responses from several excellent, wise women. Those women have a lot to teach him. If he’s smart, he’ll let them.

But since Challies needs to hear what these folks are saying, I don’t want to create any obstacles for him by insisting that he take instruction and correction from a bunch of women. So let me, instead, recommend to him some recent posts from several good, godly men:

• Joy Jon Bennett: How Tim Challies Got “Thinking Biblically” Wrong (And How We Can Do Better)

• Joy Jon Bennett: If Speaking Out Against Church Abuse I Wrong, I Don’t Want to Be Right

• Dianna Daniel E. Anderson: An Unholy Evil: Ignorance, Silence, and Abuse

• Rachel Raymond Held Evans: How [Not To] Respond to Abuse Allegations: Christians and Sovereign Grace Ministries

• Rachel Raymond Held Evans: Into the Light: A Series on Abuse and the Church

• Anthony B. Susan: Sovereign Grace Ministries and Evangelicalism’s Abuse Problem

Challies should listen to those guys. Those dudes can teach.