Echidne of the Snakes expresses well what it means to many of us non-Catholics watching the election of a new pope and the early, defining days of a new papacy. “Watching the pomp and circumstance of the papal elections,” she writes, is “a weird experience”:

In one sense it is nothing to do with me. In another, deeper sense, it is very much to do with me and people like me.

Pope Francis’ church is not my church, but the decisions he makes as the leader of his church will affect and influence my life, my family, my neighbors and my country. I cannot help but be interested, looking on with curiosity, a little hope, and a lot of dread.

Al Mohler seems almost surprised to learn that the new pope is Catholic, and takes the election of Francis as an opportunity to point out all the ways in which he, Al Mohler, is not. Like Mohler, I reject the doctrine of papal authority, but I didn’t really expect that the next pope would agree with me on that, so while I share Mohler’s disagreement, I can’t really say I share his disappointment. That’s not to say this is unimportant, but Pope’s are gonna pope. That’s to be expected.

And while I agree with Mohler on the papacy, I can’t agree with whatever it is he’s trying to say about justification “by faith alone.” I know he’s attempting to claim a historic piece of Protestant doctrine there, but the solas of the Reformation weren’t terribly coherent to begin with (sola fide tends to confusingly place more faith in faith than in the object of that faith — which is grammatically, logically and theologically backwards) and Mohler seems to strain them even further. As Jared Byas notes:

It sounds to me like Mohler is doing the exact thing he is accusing Catholics of doing. Isn’t he basically saying that “Justification is by faith alone AND your belief that justification is by faith alone”? In that case, neither the Catholics nor Mohler are saying that justification is by faith alone.

Just as I anticipated that Francis — or whoever else the new pope turned out to be — would be unsurprisingly disappointing for not being a Baptist, so too I expected any new pope would disappoint when it came to a host of other vitally important issues on which anyone likely to become pope was almost certain to be, well, wrong.

The patriarchy and hierarchy of the Catholic church is wrong. The church’s treatment of LGBT people is wrong. The church’s insistence on a nominally/officially celibate priesthood is wrong. These are serious problems and serious mistakes, but I couldn’t seriously expect any new pope not to continue repeating them. The Catholic church has been doubling down on those self-destructive errors for centuries and I do not expect that to change until crisis makes every other option impossible.

The patriarchy and hierarchy of the Catholic church is wrong. The church’s treatment of LGBT people is wrong. The church’s insistence on a nominally/officially celibate priesthood is wrong. These are serious problems and serious mistakes, but I couldn’t seriously expect any new pope not to continue repeating them. The Catholic church has been doubling down on those self-destructive errors for centuries and I do not expect that to change until crisis makes every other option impossible.

I am slightly more hopeful that the Catholic church may begin to soften its unscientific and theologically incoherent stance against contraception. That mistake is much more recent — the work of a pope overruling his theological advisers for political reasons just 44 years ago. The majority of the Catholic church has already corrected that mistake, with the vast majority of Catholic laypeople just ignoring this teaching. They do so not with any hint of the guilt that comes from actual disobedience, but only with embarrassment on behalf of the authorities still proclaiming this teaching as though faith or conscience or good sense required it, or as though anyone were listening to them.

When it comes to contraception and a whole cluster of “bedroom” related issues, my best hope is not so much that the church will change its views, but just that it will change its emphasis. Frank Bruni describes this hope well, writing that he wants to see the new pope “point the church toward a new conversation and a better focus for its spiritual energies. To have it dwell less in the bedroom, more in the soup kitchen.” Bruni says:

It’s time for the church to stop talking so much about sex. It’s the perfect time, in fact.

It’s on matters of sexual morality that the church has lost much of its authority. And it’s on matters of sexual morality that it largely wastes its breath. By insisting on mandatory celibacy for a priesthood winnowed and sometimes warped by that, by opposing the use of contraceptives for birth control, by casting judgment on homosexuals and by decrying divorce while running something of an annulment mill, the church’s leaders have enraged and alienated Catholics whose common sense and whose experience of the real world tell them that none of that is wise, kind or necessary.

The church’s leaders have also set themselves up to be dismissed as hypocrites, unable to uphold the very virtues they promulgate. Just weeks before the conclave, the most senior Catholic prelate in Britain, Cardinal Keith O’Brien, resigned his post, forgoing a trip to Rome and a vote on the next pope, because he’d been accused of, and admitted to, sexual misconduct. His case suggested the potential loneliness of a Catholic clergyman’s circumstances, and those circumstances, in the eyes of many Catholics, cast priests as odd, flawed messengers and counselors on the subject of a person’s intimate life.

And there are hopeful signs that Pope Francis — who clearly disagrees with Bruni and with me about these matters — may at least be inclined to find “a better focus for the church’s spiritual energies.”

There’s that name, for starters — Francis — which he confirmed that he chose in honor of Francis of Assisi, a saint committed to the poor, to peace, and to reverence for all of creation:

“The poor, the poor. When he spoke about the poor, I thought of St. Francis of Assisi,” said the pope, who took the name of Francis, as he continued in a bit of off-the-cuff storytelling that has become a charming hallmark of his new pontificate. “Then, I thought of the wars.”

“While the voting continued, until all the votes were counted: It is St. Francis, man of peace,” he remembered thinking to himself.

“And this is how the name came to me, in my heart: Francis of Assisi. The man of the poor, the man of peace, the man who loves and cares for creation – in this moment when we don’t have a very good relationship with creation, no?” he added.

“A man who gives us this spirit of peace, a poor man … Ah, how much I would like a poor church, for the poor!”

Good to hear. And Andrew Sullivan notes another very positive sign from that same papal press conference, when Francis said the following by way of offering his blessing on the gathered journalists:

“Given that many of you do not belong to the Catholic Church, and others are not believers, I give this blessing from my heart, in silence, to each one of you, respecting the conscience of each one of you, but knowing that each one of you is a child of God. May God bless you.”

Sullivan writes:

This kind of understanding of the diverse and multi-faith and multi-cultural modernity is something you would never have heard from Benedict XVI. … Respecting the conscience of each of you. That might seem to be the bleeding obvious – but it isn’t in the context of Benedict’s theological reign, which was far longer than his pontifical one. Benedict wanted to place conscience below revelation as authoritatively adjudicated by … himself. The central place of individual conscience established at the Second Council was left to wither in favor of a public, uniform religion. He seemed to me to want ultimately to restore the seamless cultural-political-religious unity of the Bavaria of his youth; and if the public square were empty, it had to be filled with religious authority. He tried. In the West, the public square moved in the opposite direction. He hunkered down, hoping for a smaller, purer church. What he got was a smaller one, but beset by scandal and internal division and a legacy of the most horrendous of crimes.

Francis seems to me to be taking the world as it is, but showing us a different way of living in it. These are first impressions, but there seems much less fear there of the modern world, much greater ease with humanity.

And that is a hopeful sign.

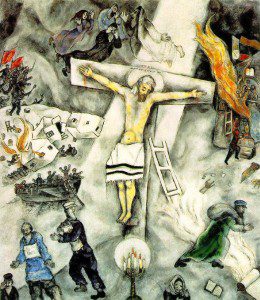

On a less important note, I also see grounds for hope in this Reuters piece, which tells us that Pope Francis says his favorite movie is Babette’s Feast and that his favorite painting is Chagall’s White Crucifixion.

At this moment in history, though, a welcome display of respect for conscience, worthy remarks on the legacy of his worthy namesake, and impeccable taste in movies and art are not what matters most for a leader in Pope Francis’ position. Above all else, he will be judged — by me, and by most of the world, and by history — on how he addresses the shameful sex abuse scandal and the church’s decades-long cover-up and complicity in denying justice to victims. That has to be his first priority, and his second, third, fourth and fifth.

Let’s start with an easy, and obvious, first step. Mark Silk spells it out very clearly:

If Francis wants to make as much of a mark by his handling of the abuse scandal as he has by his simple lifestyle, he’s got a ready-made opportunity. Last September, Bishop Robert Finn of Kansas City was convicted of a criminal misdemeanor for failing to report one of his priests for possible sexual abuse of children. Thus far, neither the Vatican nor the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has so much as issued a statement on the matter.

If Francis removes Finn from office, as he should, he will signal to the world that it’s a new day in the Church. This is an easy call to make. Let’s see if he can make it.

It should be an easy call to make. If Francis is willing to make it, then perhaps we can look upon his service with a bit more hope. If he’s not willing to make it, then that hope would be severely misplaced.