I wasn’t joking on Friday when I wrote that I’m probably guilty of the old Christian “heresy” of Patripassianism.

The Wikipedia entry on that heresy notes that, “This view is opposed to the classical theological doctrine of divine apathy.” And, well, me too — even if that contradicts 1 John 4:8, where it says “Whoever is not apathetic does not know God, for God is apathy.”

Patripassianism, roughly, is the idea that God the Father suffered in the passion of God the Son. Because, apparently, the idea that a loving Father would suffer from the suffering of a beloved son is heretical. Someone here seems deeply confused about the meaning of the words “father” and “beloved.” The early church authorities say it’s me who is confused. This makes me wonder if the early church authorities had any kids of their own. And it makes me suspect that their own dads must’ve been colossal pricks.

Patripassianism, roughly, is the idea that God the Father suffered in the passion of God the Son. Because, apparently, the idea that a loving Father would suffer from the suffering of a beloved son is heretical. Someone here seems deeply confused about the meaning of the words “father” and “beloved.” The early church authorities say it’s me who is confused. This makes me wonder if the early church authorities had any kids of their own. And it makes me suspect that their own dads must’ve been colossal pricks.

Patripassianism, by the way, is apparently related to Modalistic Monarchianism. Theologian Scot McKnight offers a description of Modalistic Monarchianism here. And here, in a post three days earler, theologian Scot McKnight seems to get his Patripassianism on in a big way. And I say good for him. His post about the various gradations of trinitarian heresies is arcane, confusing, and not obviously helpful when it comes to, say, loving my neighbor. But his post chiding the theology of miserable comforters and commending Bonhoeffer’s appeal to “the suffering God” is a helpful discussion of a necessary subject — even if it could easily be criticized for straying too near the forbidden zone of all those arcane heresies.

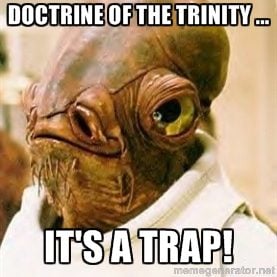

This is why the smartest thing I’ve read recently about the doctrine of the Trinity is this post from Reverend Ref back on Trinity Sunday in May:

Today is Trinity Sunday. The day when all regular preachers try to find or draft a seminarian or deacon or guest preacher to fill the pulpit. Because, really, once you get past “Three in One and One in Three,” or, “I am He and He is Me and We are All Together,” one generally begins to wander off into heresy-land — The more you talk, the more trouble you get into.

He’s right. It’s a trap. See also “St. Patrick’s Bad Analogies,” from Lutheran Satire:

As the Irish twins with the Scottish accents in that video illustrate, one is “allowed” to recite the lawyerly formulations of the Athanasian Creed, but if you stray at all from that narrow path or attempt to say anything more — any positive statements, clarifications, analogies, applications — you’re screwed. And as that video shows, this doctrine creates so many different ways in which you can be screwed that it’s hard not to suspect this was the intention — a doctrine more useful for generating and then condemning heresies than for avoiding error.

Don’t get me wrong, I believe in the Trinity, in one God in three persons. This is a historically Christian way of talking and thinking about God. It’s a helpful and insightful metaphor. And it’s a metaphor that can be supported by several passages in the Bible. But it’s not actually a biblical metaphor. It’s something that Christians have, for many centuries, laid on top of the scriptures, but it was never something we found there in any explicit form.

Set aside all the whole Monster Manual of traditional heresies and heretical -isms, where theology often starts to get into trouble is when we elevate our metaphors about God and begin worshiping and serving those metaphors rather than worshiping and serving God.

That word — “metaphor” — tends to infuriate the defenders of doctrinal purity, but it’s a necessary word. Anything else leads to laughable overreach, to the claim that we can define or confine the infinite.

I believe in God. And I believe that God, being God, is more than I can comprehend, more than I can pin down, define, contain, master or bind into a formula.

And that’s OK. Because I also believe that everything I need to know about God has been revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. And that is not a metaphor.

As for my Patripassianist tendencies, if I go for a very long walk and think about it very hard, then I can almost imagine some way in which it might be marginally useful to clarify precise ways in which God did and did not suffer in the passion of Jesus Christ. Almost. Just as I can almost conceive of some way that something called “the classical theological doctrine of divine apathy” might be something other than slanderous blasphemy. But all of that still strikes me mainly as an elaborate exercise in evading some other, far more urgent business.

All of which is to say that if anyone is looking to catechize me on the particulars of the doctrine of the Trinity, let me save you some time. I will fail that test. I’m afraid that may delegitimize everything else I have to say among those who regard that test as essential and paramount, but then this illegitimacy was already a given since I don’t have much interest in joining those who regard that test as essential and paramount. (Does that make me some kind of defiant heretic? Well, duh. What part of the words “Baptist” and “evangelical” didn’t you understand?)

If you are ever called on to parse or to try to explain the doctrine of the Trinity, remember this: It’s a trap.

Your safest response may be something like what a theology student of Ben Myers’ turned in for a class on the Trinity. Myers read the paper’s delirious conclusion and called the student aside, to say: “As your teacher, I have to tell you that this is completely unacceptable, and you must never do this again in an academic essay. As a human being, I loved it – can I post it on my blog?” (This is a response every student should aspire to inspire — but probably only once.)