“In one way or another,” Mark William Olson writes, “I suppose that we all tend to live in worlds of our own making: little worlds that feel like big worlds.”

The little world he’s writing about was, for more than a decade, my little world too. I’m fascinated by this essay of his because in recounting his own history he also retraces my own trajectory.

The little world he’s writing about was, for more than a decade, my little world too. I’m fascinated by this essay of his because in recounting his own history he also retraces my own trajectory.

Olson’s post at Christian Feminism Today is technically a book review. The book in question is Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (see also Swartz’s blog). It is a history — a history of my own tiny little world.

Swartz’s book is about a bunch of people I know — people I’ve worked for. I haven’t scored a copy of the book yet. Part of me feels like it’s a book I urgently need to read. Another part of me feels like that would be redundant. Swartz focuses on the evangelical left in the 1970s and 1980s — before my time, but this is all familiar territory for me, filled with familiar people — people I know, people I worked for or wrote for, people I’ve driven to and from airports numerous times. My little world.

But as Mark William Olson notes, Moral Minority is also a somewhat narrow view of that little world — one that perhaps identifies a bit too closely with one style of male leadership that wound up shaping what Swartz calls the “evangelical left.” Here’s Olson:

In reading [Swartz’s] narrative, you may find yourself thinking that women and feminist concerns are getting short shrift. On one level, of course, that’s simply a truthful reflection of what happened at the 1973 “Thanksgiving Workshop” that created the “Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern.” It reflects what happened at various follow-up meetings as well. Men ran things. The concerns of women were regularly pushed aside because they simply didn’t match the agenda of the dominant males. As David’s book honestly acknowledges, nervous, self-serving men sometimes rushed to bury feminist concerns, fearing that other leaders in “the evangelical world” would write off the larger effort if they thought it was giving support to women’s ordination — or some other apparent “outrage.”

In that sense, it’s a rather tragic story.

Olson links to this 2004 talk by Nancy Hardesty, in which she recounted her role in that tragic story. This is important history for anyone who wants to know why the “evangelical left” only became less than half of what it could and should have become. Here’s a bit of Hardesty’s talk:

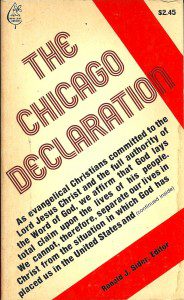

In 1973 invitations went out to about 50 people, inviting us to a conference on Evangelicals and Social Concern to meet Thanksgiving weekend at a rundown YMCA just south of the Loop in Chicago — actually right down the street from the famed Pacific Garden Rescue Mission.

At that time, I had just started Ph.D. studies at the University of Chicago Divinity School. I received an invitation because I was the former assistant editor of Eternity magazine and had taught English for four years at Trinity College. I had also taken courses at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. And I was a woman. Only five or six of us were invited: Sharon Gallagher, editor of Radix magazine; Dr. Ruth Lewis Bentley, an African American sociologist who taught at Trinity and at the University of Illinois Medical Center; Betty Danielson, a social worker from Minneapolis; Chicago black activist Wyn Wright Potter, and Eunice Schatz, director of Chicago’s Urban Life Center.

Men invited included a few of the elder statesmen of evangelicalism, representatives from various major constituencies, and a group of younger and/or more socially aware, emerging leaders. The convening committee — all male — had prepared a draft of a statement for the group’s consideration. It included lengthy paragraphs on racism, poverty, economic injustice, and militarism, but no mention of women at all. Eventually I raised my hand and pointed this out. A committee — still all male — was delegated to redraft a more succinct statement. A member of that committee, Gordon-Conwell seminary professor the late Stephen Mott, leaned across the table and whispered, “Give me something to add to the statement and I’ll try to get it in.” On a scrap of paper I wrote: “We acknowledge that we have encouraged men to prideful domination and women to passive irresponsiblity. So we call both men and women to mutual submission and active discipleship.”

Pursuing my own romantic interests at the time, I was not present when the new draft was debated. Eunice Schatz carried the cause in that debate — although she later told me that apparently we women all look alike because Carl Henry kept referring to her as “Nancy.” With the minor change of women’s “passive irresponsibility” to “irresponsible passivity,” my sentences were adopted and became part of The Chicago Declaration. Ron Sider later told me that when Billy Graham was shown the statement, he pointed to those sentences as the reason why he would not sign it.

And if Graham and the other influential gatekeepers of evangelicalism recoiled from even such a tepid endorsement of women’s equality, then it seemed prudent to the male leaders of those Chicago meetings — and of the “evangelical left” that grew out of them — to be even more timid, cautious, and slow when it came to anything that might provoke a more vehement rejection from the evangelical tribe.

As Olson said, “nervous, self-serving men sometimes rushed to bury feminist concerns, fearing that other leaders in ‘the evangelical world’ would write off the larger effort.”

Back to Olson’s review:

[Swartz] finds many to blame for the failure of “the evangelical left.” But he places part of the fault at the feet of “evangelical feminists,” especially those who formed the Evangelical Women’s Caucus … “After successfully placing their concerns on the agenda of the Thanksgiving Workshops,” he writes — and those are my italics again — “evangelical feminists largely abandoned the broader movement to build instead an organization focused more directly on women’s issues.”

So let’s see now: if you really care about something — if you consider it a deep-seated moral and biblical imperative, a much-needed response to the persistent leading of God’s own Spirit — are you supposed to be happy with simply having your concerns “on the agenda” but voted down by those who fear man more than God? Or could it be, by way of alternative interpretation, that by seeking to “save” the life of “the evangelical left,” its male leaders actually “lost” the life of that movement, much as Jesus himself had warned might sometimes be the case when we seek to play it safe?

Ironically, despite how certain parts of the book come across, David Swartz has said that he agrees with me about much of this. In an email communication, he has told me that he “admires” the way that Nancy Hardesty and the writer John Howard Yoder threw “wrenches” into the Thanksgiving Workshop. He has told me that merely getting deep-seated moral and biblical imperatives “on the agenda” should never have been enough for anyone. But he remains convinced that these divisions also “marginalized the movement.”

I would argue, however, that it was not the “wrenches” that marginalized the movement. It’s how those who sought to dominate the movement responded to those “wrenches” that was the problem.

Yes. This.

But the problem also went deeper than that. It wasn’t just that those would-be leaders were scared that “evangelical feminists” would throw a wrench into the machine they were trying to build, and that they then backed down from bolder support for women’s equality. It was worse than that.

Here’s where the discussion gets complicated, and where it involves, for me, as much confession as critique. This is, as I said, my little world, and I am complicit in it. So let me save precisely how it was worse than that for part 2.

In the meantime, please go and read the rest of Mark William Olson’s essay and of Nancy Hardesty’s address.