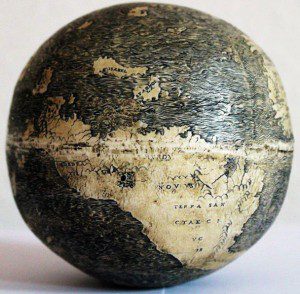

On the one hand, the maker of this globe in 1504 was woefully ignorant about the world.

It looks like South America was torn off roughly at the equator, and where the North American continent ought to be there are only a few scattered islands. The coasts and boundaries of Europe, Africa and Asia are, at best, crude approximations.

But on the other hand, this may be the oldest globe to depict the Western Hemisphere. While it’s far from perfect, it represents a huge leap forward in human knowledge and understanding.

But on the other hand, this may be the oldest globe to depict the Western Hemisphere. While it’s far from perfect, it represents a huge leap forward in human knowledge and understanding.

Whoever made this globe knew things that people a generation earlier did not know. Given when this globe was made, and given the extremely limited resources available to whoever made it, it’s a remarkable achievement.

This is how science and learning and human progress works.* The leading edge of learning one day is bound to appear vague, partial and inadequate 500 years later.

We can make maps today that are clearer, more accurate and more complete than this old globe, but we do so mindful that 500 years from now, our best efforts may appear as sketchy as this beautifully carved artifact from 1504. We go about our learning mindful that our best knowledge may, someday, be improved upon in ways we cannot imagine by people with resources we cannot imagine that will enable them to see further and clearer and deeper than we are able to see now.

That’s both humbling and inspiring. Let’s do our best, like this anonymous globe-maker did, to impress our heirs 500 years from now. They will surely notice whole continents of knowledge missing from our best efforts, but let’s try to dazzle them with our care and craftsmanship and our painstaking effort to put together the best of what we know, pointing the way to something better.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* The sentiment in this post is all quite welcome — even if it’s a bit overly sentimental — as long as the subject is cartography, or astronomy, or physics, or medicine or other fields where dramatic progress over the centuries is obvious and celebrated. But it’s mostly unwelcome if the subject is theology.

This little cartographical object lesson contradicts the mythological narrative we tend to construct around the study of theology, which regards the past as a Golden Age of perfect, complete, wholly accurate knowledge that has gradually been lost over the ensuing centuries. It’s a myth of regress just as powerful and potentially misleading as the myth of inevitable progress I flirt with in the first seven paragraphs of this post.

But it has the opposite effects. The ideal of progress is both humbling and inspiring — reminding us that our best knowledge is always incomplete and pushing us toward further inquiry and perpetual curiosity. But the ideal of regress warns against inquiry and curiosity as dangerous activities that threaten the precious remnants of the truths we have inherited. And rather than encouraging humility, it encourages arrogance — telling us that we may be worse than our ancestors, but we’ll always be better than our descendants.