David Swartz has posted a nice tribute to John Perkins. I had the privilege of spending some time with Perkins at various conferences and Christian Community Development Association events back in the day, and drove him to and from the airport a bunch of times when he came to Philly. He richly deserves such tributes.

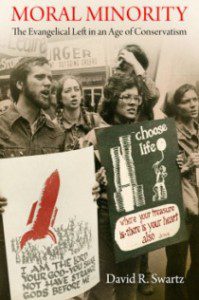

Swartz’ post is an excerpt from his book Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism. One of the main events Swartz discusses in that book is the 1973 conference that produced the first “Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern.” I was 5 years old in 1973, but I did attend the 20th anniversary conference in 1993 that produced the second “Chicago Declaration.” So here’s a brief story about that conference, which was also where I met John Perkins for the first time.

Perkins’ flight to Chicago was delayed, so he arrived late the first day and missed most of the excitement. The 300 or so “socially concerned evangelicals” who had gathered there surprised the conference organizers by voting to reject the document they had drafted for Chicago Declaration II. That meant rewriting the conference schedule so that participants could be involved in rewriting the document.

Perkins’ flight to Chicago was delayed, so he arrived late the first day and missed most of the excitement. The 300 or so “socially concerned evangelicals” who had gathered there surprised the conference organizers by voting to reject the document they had drafted for Chicago Declaration II. That meant rewriting the conference schedule so that participants could be involved in rewriting the document.

John Perkins also had another unpleasant surprise awaiting him in Chicago — a snafu with the hotel that left him without a place to stay that night.

Fortunately, those two problems fit together. A new, improved draft of the declaration needed to be written before the following morning, which meant some of us weren’t going to need the rooms we’d booked. I gave John Perkins my room and then spent the night with Dr. Roberta Hestenes and Gordon Aeschliman, who had been charged with writing the new draft.

We spent a few hours sifting through all the notes, critiques, comments and suggestions produced from the first day of the conference and then Dr. Hestenes just started pacing and preaching. She hit on this “we weep and we dream” structure and ran with it, preaching up a storm for the congregation of two gathered in her room at the Congress Hotel. I played Tertius, typing furiously and editing on the fly to transcribe her sermon, incorporating the suggestions Gordon lobbed in.

And then she kicked us out with instructions to polish up the finishing touches and show it to her at breakfast in a couple of hours. We did, although really there wasn’t a whole lot of polishing left to do, and the final document was 90 percent the sermon she’d ad-libbed the night before, incorporating all those notes and criticisms and suggestions and making them sing a little bit. Hestenes’ statement was met with applause and was approved by the whole conference as the official second Chicago Declaration. (You can read both the 1973 and 1993 “declarations” here.)

It’s 2013 — the 20th anniversary of that 20th anniversary. I don’t know if Chicago III is in the works for this fall, but I would guess it probably is. The organizers of the first two — all the friends and mentors Swartz profiles in his book — still seem convinced of the power of “declarations.” Maybe if we can get the wording just right and enlist just the right roster of prominent signatories …

That 1993 conference involved a lot of younger activist types who were excited to be there learning from people like Perkins and Jim Wallis and Ron Sider and Tony Campolo. I think for many of those young people — Gen X-ers were still young back in ’93 — the conference was both inspiring and disillusioning. The declaration was a lovely document, but it also became a reminder that manifestos written by conclaves of leaders weren’t going to produce the top-down transformation those leaders seemed to expect. Real change, those young people began to suspect, was going to have to come from the bottom-up — not from headline-grabbing declarations, but from the kind of front-line work being done by people like the foot-soldiers in Perkins’ CCDA.

The years that followed that conference turned out to be the peak of the generational cycle in which older folks dismissively fret about kids these days — all the same stuff that’s being written now about “Millennials.” Young people just didn’t seem as interested as they ought to be in doing things like organizing conferences and producing declarations. They seemed like “slackers.”

My buddy Dwight Ozard and I knew these kids weren’t slackers. We were collecting and sharing their stories in our magazine — stories of difficult, demanding work being done outside the spotlight. We turned a bunch of those stories into a series of seminars for the Cornerstone Festival. I gave the series an ironic title: “Slacker Activism.”

“Ooh,” Dwight said. “How about ‘slacktivism’?”

“Ugh,” I said. “That’s a terrible name.”