The faculty lounge is a place where teachers and professors can relax and talk amongst themselves without worrying about who might be listening in. I think that also describes the role that Books & Culture has played in American evangelicalism.

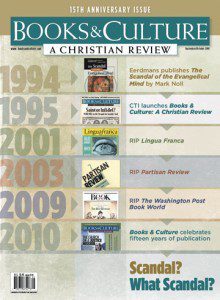

The bimonthly publication began in 1995 — a year after Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind was published. Books & Culture’s design and format revealed its ambition — to serve as a kind of New York Review of Books for evangelical Christians. It was a place where scholars could engage one another, writing long or writing deep in a way that the general-public format of Christianity Today did not allow.

But Books & Culture also, from the outset, was a forum for something else that popular evangelical publications did not allow: candid, unapologetic discussion of taboo knowledge and subject matter that had to be tip-toed around delicately when writing for a wider evangelical audience. If you are an evangelical scholar writing for Christianity Today, there are a host of Things That Cannot Be Said without sparking a heated controversy — even though none of them is actually controversial even among very conservative evangelical scholars. Whether the topic is the authorship of the pastoral epistles, or the archaeological evidence for (i.e., against) the conquest of Canaan, or more secular subjects such as the age of the Earth, Books & Culture allowed evangelicals to discuss what we’re learning honestly and openly without having to worry about setting off the hair-pin trigger alarms of either the culture warriors or the inerrantists patrolling the pages of CT for anything they perceived to be a deviation from their factually challenged version of God’s Own Truth.

But Books & Culture also, from the outset, was a forum for something else that popular evangelical publications did not allow: candid, unapologetic discussion of taboo knowledge and subject matter that had to be tip-toed around delicately when writing for a wider evangelical audience. If you are an evangelical scholar writing for Christianity Today, there are a host of Things That Cannot Be Said without sparking a heated controversy — even though none of them is actually controversial even among very conservative evangelical scholars. Whether the topic is the authorship of the pastoral epistles, or the archaeological evidence for (i.e., against) the conquest of Canaan, or more secular subjects such as the age of the Earth, Books & Culture allowed evangelicals to discuss what we’re learning honestly and openly without having to worry about setting off the hair-pin trigger alarms of either the culture warriors or the inerrantists patrolling the pages of CT for anything they perceived to be a deviation from their factually challenged version of God’s Own Truth.

Books & Culture provided a forum in which something like Peter Enns’ The Evolution of Adam could be discussed without its existence needing to be defended. Discussing such a book outside of the safety of the Faculty Lounge could be next to impossible. When most of one’s time and energy must be spent defending the existence of a book — or defending its author, its questions, its right to ask questions — then little time or energy remains for the actual discussion needed to move the conversation forward.

That’s what makes Books & Culture an invaluable safe space for evangelical scholars, and why so many of them were dismayed to learn, late last month, that the Faculty Lounge was in jeopardy of closing forever. It’s also why so many of them were willing to open their checkbooks to save it — helping to raise more than $250,000 to rescue B&C from the budget crisis that parent-company Christianity Today said would otherwise have ended it for good. And it’s also why several evangelical colleges and seminaries have pledged continued funding to ensure B&C’s financial health through the next four years.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

For an example of the sort of Things That Cannot Be Said I’m referring to above, check out this oddball little post on CT’s “Gleanings” blog discussing “Snake Handling History in Six Bites.”

Kate Tracy’s post marks the debut of NatGeo’s new reality show on snake-handling Pentecostal ministers, Snake Salvation. Tracy’s first “bite” notes the purported biblical basis for the practice:

The practice began in 1910 when an illiterate Tennessee preacher tried to literally apply Mark 16:18: “They will pick up serpents with their hands; and if they drink any deadly poison, it will not hurt them…” (ESV). However, scholars debate the authenticity of that passage.

That last sentence is a faux pas. That’s Faculty-Lounge language, not the sort of thing that can be casually admitted in a classroom in front of the children.

The scholarly debate over the authenticity of the “long” ending of Mark (verses 9-20 of chapter 16) is not, in fact, controversial — not even among conservative evangelical scholars. But among the general evangelical public, that debate is extremely controversial — so much so that it’s professionally dangerous for any evangelical scholar to publicly admit sharing any doubts about “the authenticity of that passage.” Expressing doubt about the “authenticity” of any passage in the Bible can lead to termination, blacklisting, donor-boycotts and worse.

That snake-bites story was just posted this evening and hasn’t yet received any comments. Maybe it’ll escape the notice of the Inerrancy Police and the hyper-vigilant Defenders of the Authority of the Scripture. Maybe the DotAotS will let this violation slip by because they don’t want to seem like they’re defending snake-handlers. But I’m guessing we’ll soon see some comments there directing some of their perpetual indignation toward the suggestion that any passage of their inspired holy text might not be authentic.

That’s the difference between the Faculty Lounge and the classroom — between the sort of discussion it’s possible to have in the pages of Books & Culture and the sort of discussion it’s impossible to have in the pages of Christianity Today. Mention the dubious provenance of Mark 16:9-20 in the Faculty Lounge and the other professors will nod their heads in agreement at this bit of unremarkable common knowledge. Mention such a thing in the classroom and several children will go into an uproar, loudly pointing out that 2 Timothy 3:16 clearly proves that all of Mark 16 must be authentically “given by inspiration of God.”

(And if such a student says that “Paul says in 2 Timothy 3:16 …” a prudent professor will recognize that any response involving the unlikelihood of Pauline authorship of 2 Timothy would only make matters worse. That’s a Faculty Lounge discussion and yet another of the Things Which Cannot Be Said in front of the children.)

– – – – – – – – – – – –

It’s important to note that this enforced duality isn’t exclusively a matter of financial prudence on the part of evangelical scholars. Skepticism about the role that money plays in such duality is certainly warranted — particularly since monetary threats of financial ruin are the principle weapon employed by the would-be tribal gatekeepers, who seem, themselves, motivated in large measure by the lucrative financial prospect of positioning themselves as the Defenders of the Authority of the Scriptures (see for example, “White evangelical gatekeeping: A particularly ugly example in real time“).

But convenience is as much a part of this as any supposed cowardice. Choosing to discuss certain things only amongst one’s peers in the Faculty Lounge is a way of avoiding interruptions and distractions that would likely derail any fruitful conversation.

This duality also arises from an important pastoral concern. The loudest objections to honest discussion tend to come from the professional witch-hunters — people like Al Mohler, Owen Strachan, Denny Burke, etc., who have a direct financial stake in branding themselves as the belligerent (and sanctimoniously “disappointed” — oh, how it grieves them to have to say such things …) defenders of a twisted Bonsai orthodoxy. But the larger pool of those offended are the many people who have been led astray by those same professionals. And careless candor threatens to do further harm to the victims of the witch-hunters’ “ministry” — those whose faith has been rendered fragile and brittle by accepting the all-or-nothing bundle of truth and lies that folks like Mohler are selling.

Too much honesty indelicately delivered might break a bruised reed. Someone who has been indoctrinated with, for example, the toxic all-or-nothing claims of young-Earth creationism may be in a state in which being told that the Earth is 4.54 billion years old is tantamount to being told that Jesus doesn’t love them and life is meaningless. It doesn’t matter if that’s illogical — that none of that necessarily follows or even possibly follows. They’ve been conditioned to think that it does, and so they’re not going to be able to receive brutal honesty as anything other than brutality.

We can’t indefinitely spare them the inevitable crisis that the lies of the witch-hunters have laid in their path, but we ought to do our best to make that crisis less cruel and traumatizing, not more so.

My own take on this pastoral consideration is to try to be as gentle as possible so as not to break a bruised reed, while, at the same time, hitting back — hard — at the reed-bruising charlatans responsible for causing so many to be in such a vulnerable, unsustainable state. The first pastoral obligation to the victims of such abuse is to protect them from further abuse.