The motto of Media, Pennsylvania, is “Everybody’s Hometown.” It was my hometown, too, for more than a dozen years, and it was a terrific place to live.

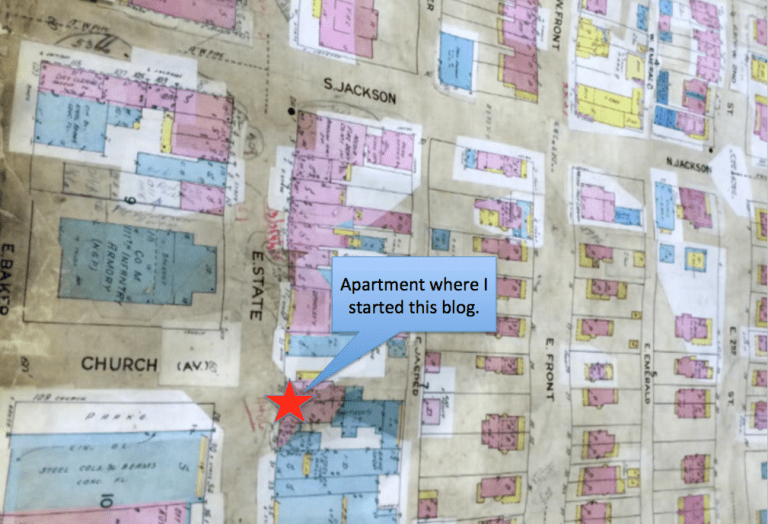

My first apartment there was right on State Street, above a shop, right by where Church Street dead-ends across from the old armory (now a Trader Joe’s). That’s the apartment where I first started this blog. Here’s a map of the old neighborhood:

That map is from 1971. The town has changed a bit since then, but it hasn’t lost its character. State Street still looks like something out of Bedford Falls. The trolley tracks keep it pedestrian-friendly and invitingly walkable. And the Delaware County Courthouse, just off the upper-right corner of that map, brings a steady flow of business supporting a lively array of great shops and eateries.

I grabbed that map from a screenshot of a video at The New York Times. It’s a piece of history — a remarkable piece of American history that I never knew about during all those years I lived in Everybody’s Hometown. That’s the map that seven burglars used to study the neighborhood before pulling off a heist that J. Edgar Hoover himself was unable to solve, despite putting more than 200 FBI agents on the case.

How did I not know about this?

Anne Laurie at Balloon Juice posted a remembrance this weekend of American Indian Movement hero Carter Camp. Camp was among the Native activists who took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C., back in 1972. While there, the AIM activists “liberated” files from the agency, passing them on to journalists and lawyers.

“We carried out box after box of documents,” inspired by the people who “stole documents from the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania,” in March 1971.

Wait, what? Media? I clicked that link and found Beverly Gage’s Slate article, “Band of Burglars: The infamous Media, Pa., break-in paved the way for the Church Committee.”

Infamous, yet neither infamous nor famous enough for me to have learned about this before:

On Tuesday, one of the biggest unsolved cases in FBI history burst wide open. In a new book, investigative journalist Betty Medsger revealed the identities of the anti-war activists who broke into the FBI’s office in Media, Pa., in March 1971 and made off with the agency’s secret files. They were, it turns out, ordinary middle-class people: “a religion professor, a daycare center worker, a graduate student in a health profession, another professor, a social worker, and two people who had dropped out of college to work nearly full-time on building opposition to the war,” Medsger writes. On March 8, 1971, they pried open the FBI office door with a crowbar, stole hundreds of files, and shook the intelligence establishment to its jackboots.

… As the story has been told ever since, the break-in itself always came across as a last-minute, amateur-hour job in which the burglars simply lucked out. In fact, as Medsger shows, they planned carefully for months, casing the FBI office night after night, holding dozens of logistical meetings, even setting up a fake door for lock-picking practice. When the big night came, they found that the FBI had put a new high-security lock on the main door, requiring the deployment of a crowbar on an alternate entrance rather than those hard-won lock-picking skills. Other than that, things went more or less as planned. Working quietly in near-total darkness, they stole every file in the office, then retreated to a Pennsylvania farmhouse to sort through what they had gathered.

The revelations went well beyond anything the activists had imagined. The FBI was, indeed, spying on the anti-war movement, just as it was spying on a vast range of civil rights, New Left, and student groups. But it was also seeking, in the words of one stolen document, to “enhance the paranoia” of anti-war activists through repeated interviews and harassment. It is worth noting that many of these efforts were far more intrusive than the passive National Security Agency surveillance recently documented by Snowden; the FBI was planting rumors, intimidating activists, and using agents provocateur. On the other hand, Hoover’s FBI never had access to truly mass surveillance technology, and even its most aggressive programs never reached anything like the indiscriminate data-gathering of today’s NSA.

… COINTELPRO turned out to be the single most important revelation to emerge from the Media files—a “counterintelligence program” of operatic proportions, still the most infamous of Hoover’s many infamous violations of civil liberties. Indeed, Hoover himself had anticipated what might happen, quietly canceling the COINTELPRO in April 1971, a month after the Media burglary. It took another four years, however, for Congress to launch a full-scale investigation of the FBI. During that time, Hoover died, the Watergate investigation blew up, the Vietnam War ended, and Richard Nixon resigned from office.

Right there in Media, in Everybody’s Hometown. Wow.