Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 213-218

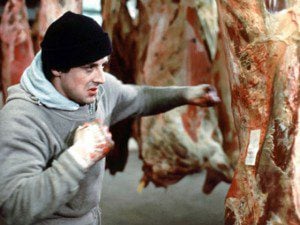

Prayer sessions seem to be these books’ version of the training montage in 1980s movies. For examples of such training montages, see Rocky, Rocky II, Rocky III, Rocky IV, Rocky V or Rocky IV.

But don’t let that list fool you, a training montage doesn’t have to be about a boxer getting ready for a fight — it could also be about a Karate Kid getting ready for a competition, or a young woman learning to dance in the Catskills, or a former hockey player learning to become a figure skater, or a group of students becoming unlikely friends during detention, or a misfit teenager learning to ski the K-12, or a misfit teenager fixing up a car, or a group of misfits coming together to form a winning baseball team or dodgeball team, or a group of misfits fixing up a boat or an old restaurant or an old theater. Or, endlessly, it can show a happy couple gradually falling in love.

The South Park guys parodied this nicely in their Team America puppet movie by setting their training montage to an upbeat, 1980s-sounding song called “Montage”:

Show a lot of things happing at once,

Remind everyone of what’s going on (what’s going on?)

And with every shot you show a little improvement

To show it all would take too long

That’s called a montage (montage)

Oh we want montage (montage)

That condensed presentation of the passage of time is one function of those scenes, but it’s not the most important one.

The key thing isn’t just to let the audience know that a lot of time and effort has occurred, but to let us know that our heroes have put in all that time and effort — and thus that they therefore deserve their eventual triumph. We’ve seen these underdogs work hard for this, so later, at the climax of the story, we feel like they’ve earned their moment of glory. We don’t feel cheated or cheapened by it. We don’t come away with the shallow sense that our heroes just got lucky, except in the sense that luck is, as someone said, “when preparation meets opportunity.” The montage showed us the preparation, so we can applaud wholeheartedly when our heroes later seize their opportunity.

The key thing isn’t just to let the audience know that a lot of time and effort has occurred, but to let us know that our heroes have put in all that time and effort — and thus that they therefore deserve their eventual triumph. We’ve seen these underdogs work hard for this, so later, at the climax of the story, we feel like they’ve earned their moment of glory. We don’t feel cheated or cheapened by it. We don’t come away with the shallow sense that our heroes just got lucky, except in the sense that luck is, as someone said, “when preparation meets opportunity.” The montage showed us the preparation, so we can applaud wholeheartedly when our heroes later seize their opportunity.

This triumph shouldn’t seem completely inevitable, though, there has to be a little bit of tension, suspense and doubt as to the ultimate outcome. So a good training montage should also include some foreshadowing and foreboding. It shouldn’t quite leave us completely confident that our heroes have mastered everything — Baby still balks at the big lift, Daniel San hasn’t quite got the hang of that one-footed crane maneuver, Justin Long still can’t catch a dodgeball, and Lane Meyer has never yet made it all the way down the K-12..

And but so, those are the main ingredients to a good training montage: the condensed presentation of the passage of time, the preparation that lends a moral legitimacy to any ultimate triumph, and the foreshadowing that makes us doubt the final outcome.

None of those ingredients is present in the prayer-as-preparation scenes here in Nicolae. But that doesn’t mean the authors aren’t using those scenes as their version of a training montage. It just means that the authors aren’t any good at what they’re trying to do.

In the little subplot unfolding in these middle chapters of Nicolae, Buck Williams and Tsion Ben-Judah are trying to figure out how to smuggle the ex-rabbi across the only remaining national border in this world. They’ve secured the use of an old school bus, but an old school bus is not a plan. And they still haven’t come up with a plan.

They’ve already spent part of this chapter prostrating themselves in ecstatic prayer, but despite the earnestness of that long session of displaying their earnestness, they’ve still got bupkis as far as ideas for how to get Tsion out of Zion.

Tsion reassures Buck, though, that the important thing here is to put in the work — do the training, and the results will follow:

“Have you prayed?”

“Constantly.”

“The Lord will make a way somehow.”

“It seems impossible right now, sir.”

“Yahweh is the God of the impossible,” Tsion said.

This is both a plot point and a lesson. If the heroes pray — earnestly and “constantly” — then God will make the impossible happen on their behalf. And thus for you also, dear reader, if you pray earnestly enough, then God will make the impossible happen on your behalf. You’ll have put in the preparation — by praying and by being deeply, deeply sincere about it — and thus when the opportunity arises, you will deserve to triumph even if that takes a miracle.

At this point, Jerry Jenkins reverts to the Jenkins Method of storytelling. It’s not enough just to show that the heroes are sincere and thus deserving of a miraculous victory. To make sure that readers understand this, Jenkins will tell them. Thus we get a page-long monologue from Tsion Ben-Judah:

“This is very hard for me. In my flesh, I would rather not go on. Part of me very much wants to die and to be with my wife and children. Only the grace of God sustains me. Only he keeps me from wanting to avenge their deaths at any price. I foresee for myself long, lonely days and nights of dark despair. My faith is immovable and unshakable, and for that I can only thank the Lord. I feel called to continue to try to serve him, even in my grief. I do not know why he has allowed this, and I do not know how much longer he will give me to preach and teach the gospel of Christ. But something deep within me tells me that he would not have uniquely prepared me my whole life and then allowed me this second chance and used me to proclaim to the world that Jesus is Messiah unless he had more use for me.

“I am wounded. I feel as if a huge hole has been left in my chest. I cannot imagine it ever being filled. I pray for relief from the pain. I pray for release from the hatred and thoughts of vengeance. But mostly I pray for peace and rest so that I may somehow rebuild something from these remaining fragments of my life. I know my life is worthless in this country now. My message has angered all those except believers, and now with the trumped-up charges against me, I must get out. If Nicolae Carpathia focuses on me, I will be a fugitive everywhere. But it makes no sense for me to stay here. I cannot hide out forever, and I must have some outlet for my ministry.”

Let’s pause for a moment here to be grateful that early on Jenkins made the decision to spare us his attempts at conveying Tsion’s “thick Hebrew accent.” When we first met the soon-to-be-ex- rabbi, his lines were written like this: “Ees dis Chamerown Weeleeums? … Dees ist Dochtor Tsion Ben-Judah.” Thankfully, even Jenkins quickly tired of that, and settled instead on the expedient solution of just having Tsion speak like everyone else while occasionally reminding us that we should be imagining everything he says as though it were being spoken in a thick accent.

So that monologue could have been much worse.

The point of it, though, was to assure us that Tsion’s “faith is immovable and unshakable,” and that he remains steadfast, yet humble. Jenkins achieves this by having Tsion tell us that his faith is immovable and unshakable, and the he remains steadfast, yet humble. All of which means, apparently, that his prayers deserve answers and that he deserves a miracle.

After a full day and night of continuous prayer, though, it’s time for our heroes to set out and they still don’t have a plan.

“The sky is getting black, and unless we want to wait another 24 hours, the time to move is now,” Michael says. “What shall we do?”

Buck looked to Dr. Ben-Judah, who simply bowed his head and prayed aloud once more. “O God, our help in ages past –”

Buck immediately began to shiver and dropped to his knees.

Yep, more earnest prayer.

Don’t misunderstand me here — I haven’t gotten anything against prayer itself. But the function and the portrayal of prayer in these chapters is revealingly bad.

Part of the problem, I think, is the authors’ inability to reconcile this portrayal of prayer as a plot development and also as an instructive spiritual lesson for readers. The latter seems to undermine the former by asking us to look too closely at how our heroes are praying, and what specifically they’re doing that we’re supposed to emulate if we hope to produce similarly miraculous results in our lives.

And if we look closely at that, it becomes all too obvious that the authors themselves have no idea.

If we turn to these chapters for advice or instruction on how to pray, we find they offer precious little beyond the insistence that we have to be really sincere about it. Like really, really sincere. Like, really, really, really, really, really sincere, even.

Prayer thus becomes an exercise in which we attempt to conjure up a sensation of absolute sincerity. It thus also becomes an exercise in which we carefully monitor our physical and emotional sensations to gauge that level of earnestness and just, really, Lord, just, really try our best, Lord, to just, Lord, really just make ourselves feel as utterly, totally sincere as we can.

I’m not sure what word best describes such an exercise, but that word would not be “prayer.”

Before Buck and Tsion get on board their school bus, though, we’re treated to yet another scene in which they repeat this exercise. With every head bowed and every eye closed, Tsion begins reciting the words to old Christian hymns as:

Buck immediately began to shiver and dropped to his knees. He sensed the Lord impressing upon him that the answer was before them. Echoing in his mind was a phrase that he could only assume was of God: “I have spoken. I have provided. Do not hesitate.”

Buck felt humbled and emboldened, but still he didn’t know what to do. If God had told him to go through Egypt, he was willing. Was that it? What had been provided?

Michael and Tsion were now on their knees with Buck, huddled together, shoulders touching. None of them spoke. Buck felt the presence of the Spirit of God and began to weep. …

Ooh, good. Weeping is good. The danger now, though, is that this earnest manifestation of earnest earnestness will, because it’s such a good sign, cause a momentary sensation of happiness that he’s finally getting the sought-after tears to come, and that brief moment of excited elation can have the unfortunate side-effect of putting a stop to the tears. That’s how tears work when it comes to overacting, at least, and this exercise of “prayer” as the pursuit of the sensation of sincerity resembles nothing so much as overacting.

Buck felt the presence of the Spirit of God and began to weep. The other two seemed to be shivering as well. Suddenly Michael spoke, “The glory of the Lord shall be your rear guard.”

Words filled Buck’s mind. Though he could barely pronounce them through his emotion, he blurted, “You give me living water and I thirst no more.” What was that? Was God telling him he could travel into the Sinai desert and not die of thirst?

Tsion Ben-Judah prostrated himself on the floor, sobbing and groaning. “Oh God, oh God, oh God –“

Buck seemed to be doing so well — kneeling, weeping a bit, and struggling to pronounce words. Then Tsion has to one-up him with an even more elaborate show of sincerity. Nobody likes a topper.

This goes on for a bit longer, then:

It was as if Buck had been steamrollered by the Spirit of God. Suddenly he knew what they must do. The pieces of the puzzle were all there. He, and they, had been waiting for some miraculous intervention. The fact was, if God wanted Tsion Ben-Judah out of Israel, he would make it out. If he did not, then he would not. God had told Buck in a dream to go another way, through Egypt. he had provided transportation through Michael. And now he had promised that his glory would be their rear guard.

“Amen,” Buck said, “and amen.” He rose and said, “It’s time, gentlemen. Let’s move.”

Buck is rising up to the challenge of his rivals. He went the distance and he’s not gonna stop. He will fight just to keep them alive.

Dr. Ben-Judah looked surprised. “Has the Lord spoken to you?”

Buck shot him a double take. “Did he not speak to you, Tsion?”

“Yes! I just wanted to make sure we were in agreement.”

Again, let me say that I like the idea of believers praying for God’s guidance, and of doing so as part of a process to bring us all “into one accord” as to how to proceed together. But that little exchange highlights one of the ways that can go wrong when we elevate the feeling of sincerity and the display of that feeling as the highest form of spiritual truth. I read the lines Jerry Jenkins wrote there, and I imagine a similar conversation:

“You’re saying you have a message from God?”

“Of course, of course. All the time with the messages from God. Isn’t that how it works for you?“

“What? Oh, right. Yeah. Of course. Messages from God. All the time. And I actually got mine first. I was just waiting for you to catch up.”

“Really? So what was the message you got?”

“Same as yours, probably. What was yours?”

“You first …”

“No, you first, I insist …”

Their approach, in other words, seems like a recipe for self-deception. Or for mutual self-deception. Or for whatever you call it when everybody’s engaged in a bit of mutual self-deception but nobody is even convinced enough to actually be deceived.

As they board Michael’s Jordan riverboat, Tsion says:

“This is exciting, is it not? We are talking confidently about getting into the Sinai, and we have no idea how God is going to do it.”

“Exciting” is one word for it, I suppose.