Thomas Kidd’s short post today on African American poet Phillis Wheatley gave me pause when it came to his discussion of George Whitefield — the great evangelist of the Great Awakening whose death was the subject of Wheatley’s first popular poem.

I didn’t realize that Whitefield was a slave-owner — an untroubled, unrepentant, complacent slave-owner.

But he was actually worse than that.

Growing up in the white evangelical subculture, I knew a bit about Whitefield. We studied the Great Awakening in history classes at my evangelical Christian school, and every such lesson included descriptions of Whitefield’s spectacular gifts as a preacher, the huge crowds his outdoor sermons drew, and the revival that followed in his wake.

Nearly everything I encountered about Whitefield was along the lines of this brief hagiography from a few years ago in Christian History magazine. That article mentions that Whitefield first came to the colonies as a missionary to Georgia. And it recalls the famous orphanage he founded in Georgia — without mentioning that this orphanage was also a plantation built upon stolen labor and stolen lives.

Here is all that history has to say about Whitefield and slavery and Georgia:

Whitefield also made the slave community a part of his revivals, though he was far from an abolitionist. Nonetheless, he increasingly sought out audiences of slaves and wrote on their behalf. The response was so great that some historians date it as the genesis of African-American Christianity.

Everywhere Whitefield preached, he collected support for an orphanage he had founded in Georgia during his brief stay there in 1738, though the orphanage left him deep in debt for most of his life.

But its’ far, far worse than that.

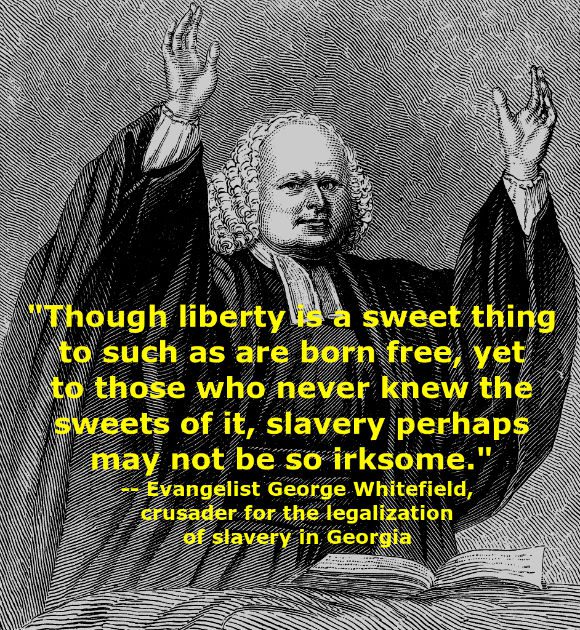

When Whitefield first founded his orphanage in 1738, slavery was illegal in the colony of Georgia. The evangelist was certain, however, that “hot countries cannot be cultivated without negroes,” and that legal slavery would be the key to making his endeavors there profitable. So George Whitfield — who was, as Christian History said, “probably the most famous religious figure of the 18th century” — began lobbying the crown and the trustees of the colony to make slavery legal there.

Whitefield’s efforts were essential to that cause. Without his hard work, slavery might never have become legal in Georgia.

Let that sink in. Ponder that — the immensity of it, the consequences of it, the incalculable toll and immeasurable injustice of it.

And then ask yourself whether it is possible that such a grievous evil could be so inextricably woven in with the revivalism of the Great Awakening without in any way influencing the form, shape, and substance of that revival and the kind of Christianity it planted here in American soil.

Ah, but Whitefield was simply a “man of his time.” Hogwash. John Woolman was also a man of Whitefield’s time.

But my point here is not to pass judgment on George Whitefield. My point here is to learn from corrosive rot that infected the gospel according to George Whitefield so that we can learn to guard ourselves against the same lethally evil disease — to identify, root out, and cauterize every instance of its lingering presence in our faith, theology, culture and law.

Here are the symptoms. This is deadly. This is what death looks like, from Whitefield’s correspondence — a letter he wrote on March 22, 1751:

As for the lawfulness of keeping slaves, I have no doubt, since I hear of some that were bought with Abraham’s money, and some that were born in his house.—And I cannot help thinking, that some of those servants mentioned by the Apostles in their epistles, were or had been slaves. It is plain, that the Gibeonites were doomed to perpetual slavery, and though liberty is a sweet thing to such as are born free, yet to those who never knew the sweets of it, slavery perhaps may not be so irksome. However this be, it is plain to a demonstration, that hot countries cannot be cultivated without negroes. What a flourishing country might Georgia have been, had the use of them been permitted years ago? How many white people have been destroyed for want of them, and how many thousands of pounds spent to no purpose at all? Had Mr Henry been in America, I believe he would have seen the lawfulness and necessity of having negroes there. And though it is true, that they are brought in a wrong way from their own country, and it is a trade not to be approved of, yet as it will be carried on whether we will or not; I should think myself highly favoured if I could purchase a good number of them, in order to make their lives comfortable, and lay a foundation for breeding up their posterity in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. You know, dear Sir, that I had no hand in bringing them into Georgia; though my judgement was for it, and so much money was yearly spent to no purpose, and I was strongly importuned thereto, yet I would not have a negro upon my plantation, till the use of them was publicly allowed in the colony. Now this is done, dear Sir, let us reason no more about it, but diligently improve the present opportunity for their instruction. The trustees favour it, and we may never have a like prospect. It rejoiced my soul, to hear that one of my poor negroes in Carolina was made a brother in Christ. How know we but we may have many such instances in Georgia ere it be long?

This is not good news. This is not salvation. This cannot be reconciled with the gospel.

The man who wrote those words was surely, at some fundamental, essential level, wrong about the meaning of the good news and of salvation.

And yet today, in 2014, the white evangelical understanding of good news and salvation is still shaped and bounded by the model and teachings of the man who wrote that passage above.

That’s a problem.

That’s a huge problem.