Brent Plate reflects on HBO’s The Leftovers, offering the term “apocalyptabuse” to describe “a strong tinge of emotional mistreatment” that seems to accompany Rapture-mania wherever it latches on:

In the evangelical environment in which I lived, the imminent end of the world was assumed, and the rapture (the taking up to heaven of the faithful) was assured. People would be taken, and others would be left behind.

… The end was near. That much we knew. Only, how could we be sure we were on the right side? What about that accidental “goddamn” that slipped out when I tripped up? That mysterious aching desire for the cute girl in the second row of homeroom? And, most troubling, did that last altar call really take? Was that last prayer to ask Jesus into my heart really sincere? Did I get the metaphorical nuance of it all sufficiently?

More than anything, as Lindsey’s books and the scary movies made sure, we had the hell scared out of us. It was not uncommon for a child in our circles to lie in bed in terror wondering whether we too might wake up to an empty house, just like the woman at the beginning of A Thief in the Night.

Many of the avid fans of the Left Behind series describe this same anxiety at the Facebook page for the new movie. The filmmakers posted a clip showing an elementary school teacher’s response of B-movie horror as she stands alone in a classroom littered with the clothing of Raptured children. Throughout comments, many of the eager fans share how they used to be scared by scenes like that, but now they’re no longer afraid — they’re sure they’re ready to be Raptured at any moment.

But the desperate fear Plate and those commenters describe is not unique to Christian communities obsessed with “the End Times” and Rapture mythologies. That fear just takes on a particular form in those communities. A similar fear is also common wherever a fierce belief in eternal Hell is preached, taught and believed.

“If I should die before I wake …” says the familiar Christian prayer for small children at bedtime. What a ghastly thought to ask a child to entertain just when you want them to be relaxing into a restful night’s sleep. “Oh, yes, little one, here’s one last reminder before I turn out the lights — you may die before you wake.”

For Christians on Team Hell, that thought inevitably produces the same kind of second-guessing anxiety that Plate describes. “Did that last altar call really take? Was that last prayer to ask Jesus into my heart really sincere?”

That focus on “sincerity” is especially troublesome. Children lie awake, poking and prodding and re-examining the sincerity of their sincerity, slowly turning into neurotic little Descartes, recognizing that the only thing they can be certain of is their own doubting. And then, since sincerity allows for no rational proof, children begin to seek some form of visceral proof — a feeling, emotion or sentiment in the gut. (That can lead to deeper, longer-term problems, as through the process of seeking such a visceral proof of their own sincerity, those children gradually learn to manufacture it, thereby learning that faith is primarily a matter of sensation and emotion.)

I’d say both of those — teaching children the ideologies of the Rapture or of Team Hell — involves more than just a “tinge” of emotional mistreatment.

But it’s also true that some such middle-of-the-night anxieties are unavoidable for anyone, regardless of what they have been taught to believe about the resurrection of the dead or the life of the world to come. Because it’s always true that any of us might, in fact, die before we wake. And it is always true that all of us will, someday, inevitably, die.

Rapture ideology, I believe, is a product of anxiety about death. It’s a way of coping with the fear of death by denying its inevitability, inventing a way that some special few of us will get to escape it.

“Can you imagine, Rafe? … Jesus coming back to get us before we die!”

That’s why I thought the first episode of The Leftovers was so well done — and also why I find the series difficult to watch.

That’s why I thought the first episode of The Leftovers was so well done — and also why I find the series difficult to watch.

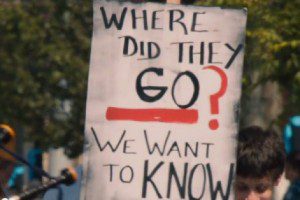

Here is the premise of The Leftovers: People disappear. They go away. Where? We don’t know. Why? We don’t know. No one can tell us what it means.

Brent Plate calls that a “secularized” Rapture story, which isn’t wrong. But in simpler terms, it’s about death.

That’s a fertile, vital, fruitful theme, and an important one. But it’s also a bit, well, heavy. So I found myself appreciating and admiring The Leftovers more than enjoying it.

The show needs to be a lot funnier. It has its moments — the Gary Busey line was pretty good — but they’re few and far between. Gravity requires levity — not just as a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine more palatable, but because comedy is true. Just consider the wordplay in the previous paragraph, describing death as fertile, vital and fruitful. Those aren’t particularly funny jokes, but they approach something true that needs to be said about death.

Even if the show’s creators are telling us a story about the absence of resolution and meaning — if they’re saying, “there is no point … that’s the point” — then what we have here is a picture of absurdity. And absurdity, even in its darkest, most mordant form, is always a kind of joke.

To an extent, my complaint that the show isn’t funny enough is a sectarian critique. We Christians always insist on a bit of resurrection. We believe death is the set-up, not the punchline. (And we’re not the only ones who share that suspicion.)

But whether or not we Christians are right about how death works, humor is undeniably a big part of how humans work. That’s no less true when we’re confronted with death and loss and grief. Denial, bargaining, anger, depression and acceptance are not just the five stages of grief. They’re also the five kinds of jokes we humans make — and laugh at — when confronted with tragedy.

In any case, by turning our focus to the mystery of death, The Leftovers is far more true to the supposed “Rapture” passages of the Bible than any of the “Bible prophecy” studies or fiction series.

But as the days of Noah were, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be. For as in the days before the flood, they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day that Noah entered the ark, and did not know until the flood came and took them all away, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be. Then two men will be in the field: one will be taken and the other left. Two women will be grinding at the mill: one will be taken and the other left. Watch therefore, for you do not know what hour your Lord is coming.

Tim LaHaye says that passage describes the Rapture. I say it describes death. Perhaps, as LaHaye insists, I’m wrong about that, but his interpretation has already been wrong for more than 1900 years. If that passage were about “the Rapture,” then it has been wrong for every generation of Christians that ever lived until now. If it is about death, then it has been undeniably true for every one of those prior generations.

The people in the story of Noah, Jesus said, were oblivious “until the flood came and took them all away.” The flood didn’t rapture those people. They died. Two men will be working, and “one will be taken.” He’s not getting raptured either.

One will be taken and the other left. That’s us, for now. The Leftovers. We’re still here.