So here’s another Jesus-story about apologies and forgiveness. This is from Luke 19:

[Jesus] entered Jericho and was passing through it. A man was there named Zacchaeus; he was a chief tax collector and was rich. …

When Jesus came to the place, he looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down; for I must stay at your house today.”

So he hurried down and was happy to welcome him. All who saw it began to grumble and said, “He has gone to be the guest of one who is a sinner.”

Zacchaeus stood there and said to the Lord, “Look, half of my possessions, Lord, I will give to the poor; and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I will pay back four times as much.”

Then Jesus said to him, “Today salvation has come to this house.”

Zacchaeus is a public figure who is guilty of serious wrongdoing that harms others. Then he meets Jesus.

Zacchaeus doesn’t apologize and he doesn’t beg for forgiveness. He does something far more meaningful — he makes things right.

Zacchaeus had become a wealthy, powerful man. “Salvation” didn’t give him the option of remaining that way. He couldn’t simply apologize, promise to stop defrauding people in the future, and then sanctimoniously remind everyone that they were obliged to forgive him for having defrauded and oppressed them because that, after all, is Jesus’ message.

For Zacchaeus, salvation wasn’t cheap.

Contrast that with the pious rituals of public apology and forgiveness that have now become the routine in American churches. Zack Hunt describes this well:

Repentance, like salvation found in a moment at an altar call, can be had instantaneously for a few magic words. Say the right thing – or have your PR guy craft the right apology for you – and Christians everywhere are expected to offer you instant absolution, no questions asked. Any concrete actions on your part to demonstrate a truly contrite heart and desire to follow a new path are not only not expected, but calling for such action is considered almost non-Christian because it seems to run counter to our faith-alone gospel.

Unfortunately, the people in power who seem to so often find themselves in this sort of situation have grown wise to the deal we’ve created. They know how to work the system. They know that if they just say the right thing and go through a few simple motions, they can essentially continue on doing what they’ve been doing in the same way they’ve been doing it for as long as they want.

All the while, we pat ourselves on the back for our forgiving hearts while shaming our brothers and sisters who are more skeptical of someone whose repentance seems to be completely exhausted by their words.

Those “people in power” who have learned “how to work the system” have thereby distorted the system. They have changed the way it works — which is to say that it doesn’t work unless we account for those changes and distortions.

I was a bit critical of Scot McKnight the other day precisely because he refused to acknowledge how the system has been changed or even that the system has been changed. McKnight’s post arguing that “The Jesus Posture Is the Way of Forgiveness” suffers from a pious abstraction that distracts from the actual world in which such pieties must be made incarnate. Everything he says about loving our enemies, emulating Christ, and forgiveness is abstractly correct, but fuzzily incorrect in practice.

I was a bit critical of Scot McKnight the other day precisely because he refused to acknowledge how the system has been changed or even that the system has been changed. McKnight’s post arguing that “The Jesus Posture Is the Way of Forgiveness” suffers from a pious abstraction that distracts from the actual world in which such pieties must be made incarnate. Everything he says about loving our enemies, emulating Christ, and forgiveness is abstractly correct, but fuzzily incorrect in practice.

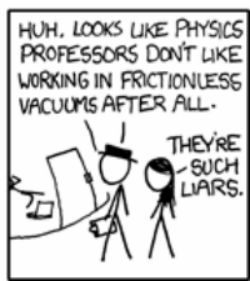

It’s a bit like those physics formulas you learned in high school. Yes, that’s how it works, but it only works that way in a frictionless vacuum. And none of us actually lives in a frictionless vacuum.

In the actual world that we actually live in, those basic formulas are still true, but they’re also a bit more complicated.

Elizabeth Esther addresses some of those complications, asking “Does Jesus ask us to accept empty apologies?” She responds to those who, like McKnight, insist that “The Jesus Posture” requires us to A) accept such apologies at face value, and B) urge others, including direct victims, to accept such apologies as well:

It isn’t our place, as outsiders, to accept apologies on behalf of those who are being directly harmed by Driscoll. That’s like an outsider coming to me and saying, “Hey, I forgive your grandfather for abusing you in his cult! You should, too!” Wait. What?! Outsiders have no place accepting apologies or forgiving an abuser on my behalf. That’s MY job. Outsiders do have jobs to perform: ie. provide support and safe places, help spread awareness – but telling everyone to “accept apologies” is not one of those jobs.

By urging people to “accept” Driscoll’s apology, Merritt places the onus on the victim instead of on the abuser. The underlying idea, here, is that victims of abuse are supposed to Keeping Doing Things; ie. accept apologies, be supportive, not get angry, remain positive … and furthermore, do all this before the abuser stops the abuse. Is this what Jesus meant when He told us to forgive? I don’t think so.

(Emphatic emphases original.)

This abstract distortion of Jesus’ teaching about unconditional forgiveness becomes a weapon used against the very people Jesus identified with — the victims, the poor, the powerless, the “least of these.”

And, as Rachel Held Evans writes, it doesn’t just become a weapon wielded by the powerful, it also becomes a shield and armor to protect them. The same abstracted version of abstracted forgiveness and “grace” that is used to compel victims to forgive is also used to silence those victims and anyone else who might be trying to protect them or to prevent future harm:

Confronting bullying and abuse is not “bickering.” It’s the right thing to do. It’s standing in solidarity with the very people Jesus taught us to prioritize — the suffering, the marginalized, the vulnerable. When it comes to injustice, a far more important question to me than “What will the world think if they see us disagreeing?” is “What will the world think if they don’t?” We don’t protect our witness to the world by hiding abuse. We protect our witness by exposing it, confronting it, stopping it. Defending the defenseless is an essential (and biblical) part of our calling as followers of Jesus. We don’t just abandon it when the bully happens to be a Christian.

Nor should we abandon it just because some Christians have learned “how to work the system.”