Peter Enns looks at the latest depressing study showing that facts are not persuasive when people’s religious or ideological preconceptions are at stake. Those contradictory facts are often known, just not accepted. They’re not rebutted, simply rejected outright as incompatible with the person’s preferred anti-factual — i.e., false — worldview.

(I dislike that word “worldview,” but it’s appropriate here since the very people who talk most about “worldviews” are precisely the same people who tend to reject facts in favor of them.)

Here’s the nut of Brendan Nyhan’s New York Times article that prompted Enns’ response:

In a new study, a Yale Law School professor, Dan Kahan, finds that the divide over belief in evolution between more and less religious people is wider among people who otherwise show familiarity with math and science, which suggests that the problem isn’t a lack of information. When he instead tested whether respondents knew the theory of evolution, omitting mention of belief, there was virtually no difference between more and less religious people with high scientific familiarity. In other words, religious people knew the science; they just weren’t willing to say that they believed in it.

Mr. Kahan’s study suggests that more people know what scientists think about high-profile scientific controversies than polls suggest; they just aren’t willing to endorse the consensus when it contradicts their political or religious views. This finding helps us understand why my colleagues and I have found that factual and scientific evidence is often ineffective at reducing misperceptions and can even backfire on issues like weapons of mass destruction, health care reform and vaccines. With science as with politics, identity often trumps the facts.

“The problem isn’t a lack of information,” so the solution can’t simply be a presentation of more and better information — no matter how patient, polite or persuasive the presentation of that information may be.

Or, as Enns puts it, “Education doesn’t correct bad thinking if one’s narrative relies on that bad thinking.”

Enns thus concludes that, “One also has to offer an alternate coherent and attractive structure whereby people can handle these new ways of thinking without feeling as if their entire faith and life hang in the balance.”

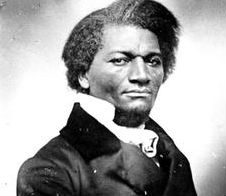

More than a century before Nyhan and Kahan began studying this phenomena, Frederick Douglass had already reached the same conclusion they arrived at. “On what branch of the subject do the people of this country need light?” he asked — meaning, in other words, that the problem isn’t a lack of information.

More than a century before Nyhan and Kahan began studying this phenomena, Frederick Douglass had already reached the same conclusion they arrived at. “On what branch of the subject do the people of this country need light?” he asked — meaning, in other words, that the problem isn’t a lack of information.

The facts are known. The facts are known to be the facts. But those facts are simply rejected when they cannot be accommodated by a pre-existing “worldview” that is dependent on rejecting them.

Therefore, Douglass concluded, “it is not light that is needed, but fire”:

Scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

Ridicule? Reproach? Sarcasm? Emotion? How terribly uncivil of him.

I agree with Peter Enns when he calls for “alternative narrative structures” to replace the unsustainable “worldviews” that force their adherents to embrace unreality. The problem isn’t a lack of information, the problem is bad stories. And the best response to bad stories is to offer better stories.

But how can we make better stories heard when those trapped by their failing stories refuse to hear them?

Here, as usual, Douglass was right. With fire — with “scorching irony … biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke.”

There’s no point in abstractly debating whether such things are nice or polite or civil. They are, as he said, “needed.”