Yesterday we discussed how the “biblicism” of white evangelicalism is a relatively recent historical innovation — something that could not and did not exist until the printing press and biblical translation had progressed enough to allow most Christians to own and read their own Bibles for themselves.

As a simple matter of history and technological possibility, such biblicism was impossible for the first 15 centuries of Christianity. During all that time — the majority of the history of the faith — most Christians simply didn’t have the access to the Bible that Christians today take for granted. For the vast majority of Christians, the Bible was something you heard read by others in church. Something like a daily devotional “quiet time” just wasn’t an option.

That began to change in the 16th century and into the 17th, when technology, translation and literacy for the first time in history made it possible for revivalist, “Bible-believing,” biblicistic evangelicalism to emerge.

But white evangelicalism did not emerge in a vacuum. It evolved in an ecosystem. It grew up in, and was shaped by, the context around it. No sooner did Christians gain this newfound access to their own Bibles than they began to argue over the meaning of those Bibles, and what those scriptures had to say about the world around them. For the first time in history, these Christians had to figure out, for themselves, how to read their Bibles, and they did so based on how they wanted to read them to apply to the world around them.

And that brings us to this post from the Moorfield Storey Blog, “Evangelicalism and Slavery: Historic Allies, Not Enemies.” That post takes a critical look at the 2006 Michael Apted film, Amazing Grace, which tells the story of Reed Richards William Wilberforce and his efforts to outlaw the slave trade in Britain.

Wilberforce is, indeed, someone who deserves all the laurels and honors we can send his way. He played a vital role in the history of the abolition of slavery. But, as the MSB post says, the film suggests more than that — presenting its story as though Wilberforce invented the abolitionist movement:

The city state of Venice outlawed slavery in 960, Iceland abolished it in 1117, Spain did so in 1542, Poland in 1588, etc. Wilberforce gets attention for two reasons. First, English-speaking people tend to only pay attention to the history of English-speaking countries. Second, Wilberforce is promoted by fundamentalists because he was an evangelical Christian. Evangelicals are working hard to take credit for abolitionism.

Notice all these other countries where slavery was abolished first, which evangelicals do NOT mention. None of them were Protestant, and none had a prominent evangelical involved. So, they can’t take credit. Thus, as far as modern evangelicals are concerned, abolitionism started with Wilberforce.

Yes. The problem isn’t that Amazing Grace is a hagiography of William Wilberforce. The problem is that it is a hagiography of contemporary white evangelicals — projecting ourselves back in time with Wilberforce as our surrogate and stand-in.

That’s a problem, not just because it fudges Wilberforce’s story, but because it rewrites our own history in an attempt to consecrate our present-day status quo. That reduces Wilberforce — who, again, deserves better — into just another incarnation of the Hollywood White Savior. It makes him Kevin Kline in Cry Freedom, or Gene Hackman in Mississippi Burning. Or Stellan Skarsgård in Amistad. We can tell Wilberforce’s story, or we can flatter ourselves by making him our revisionist Mary Sue. But we can’t do both. (See also: Eric Metaxas’ autobiography of Mary Sue Bonhoeffer.)

The Moorfield Storey Blog discusses the way a similar self-hagiography is at work in the popular mythology of Wilberforce’s contemporary, slaver-turned-hymn-writer John Newton:

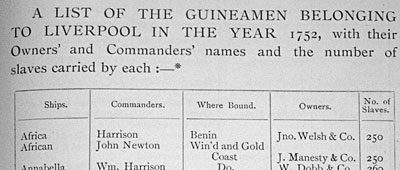

Amazing Grace implies that Newton converted to evangelical Christianity and, as a result, became an abolitionist. This actually is not true. While both are true — eventually — the one was not caused by the other. Newton, in fact, was a slaver. His job was to sail slaves to the Americas where they were sold. Newton continued to do this well after his so-called conversion. Newton became an evangelical in 1748. He continued selling slaves until he retired from the sea in 1754 because he wanted to become an Anglican priest. Newton was quite happy to use violence against slaves and used torture to wring confessions from those he thought guilty of planning their own freedom.

A third of a century after his retirement as captain of slave ships Newton came out in support of abolitionism. So, if his conversion to evangelicalism made him an abolitionist, it took almost four decades to do so.

Newton wrote that after his conversion he just never gave a thought to the morality of slavery. He said he never thought of it and that not a single friend, evangelical or not, thought it wrong to enslave people. He considered his job as slaver “the line of life which Divine Providence had allotted to me.”

We like to tell ourselves that Newton became an abolitionist because he converted to Christianity, but it would be more accurate to say that he eventually became an abolitionist despite his conversion. That conversion immersed him in the biblicism of evangelicalism, which at that time approached the subject of slavery with the same “literal” and “plain-reading” hermeneutic that white evangelical biblicism promotes today.

(“Hermeneutic” is seminary-speak for the overall way we approach and interpret a text. Biblicism tends to involve pretending one doesn’t need a hermeneutic, and therefore doesn’t have one, which is never possible nor true.)

(“Hermeneutic” is seminary-speak for the overall way we approach and interpret a text. Biblicism tends to involve pretending one doesn’t need a hermeneutic, and therefore doesn’t have one, which is never possible nor true.)

That hermeneutic — or anti-hermeneutic, really — requires one to acknowledge all of the biblical passages permitting, commending or commanding slavery and to treat them as “The Word of God” and, therefore, as “the ultimate authority and measure of all truth.” And because this biblicist anti-hermeneutic cannot allow for any contradictions or transformations in the infallible, unchanging “Word of God,” it glosses over, spiritualizes, “harmonizes” and otherwise dismisses all of the many, many liberationist biblical texts and themes, which it cannot permit to be read as conflicting with or undermining — let alone over-ruling — the proof-texts that defended slavery.

Evangelical abolitionists like Wilberforce, Newton (eventually), and Lewis Tappan (Sarsgård’s character in Amistad) appealed to a different hermeneutic, and were therefore severely criticized by their fellow white evangelicals for rejecting the authority of the scriptures, abandoning the Bible, denying the Word of God, etc. etc. (For a sense of those anti-abolitionist critiques, just go to the Gospel Coalition blog and look at everything they have to say about, for example, Rachel Held Evans. Different century, same argument.)

John Newton became a born-again white evangelical Christian on March 10, 1748, but he did not cease to be a slave trader. He simply became a slave-trader who no longer drank, swore or gambled.

That was the effect of Bible Christianity. But this was not a side effect, it was the purpose of the thing. This was the effect that the anti-hermeneutic of Bible Christianity was designed to produce — a form of Christian piety that defended unjust structures, slavery in particular. Bible Christianity defended slavery because that was what it was designed to do.