My friend was nervous about meeting her new boyfriend’s mother for the first time.

“She’s Catholic,” she said.

“You’re Catholic,” I reminded her.

“Yeah, but she’s, like, very Catholic.”

Ah. That’s different.

I’ve known lots of people who might, in the usual sense of very, be described as “very Catholic.” In my first job after college, I was part of an interfaith network that included the Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of St. Joseph, and a bunch of other impressive, formidable women from a host of other Catholic orders. These were people whose lives were wholly shaped by their faith and wholly devoted to their various remarkable ministries. Their lives exemplified the Christian virtues and the fruits of the Spirit.

But people like that aren’t what we mean when we talk about someone like my friend’s future mother-in-law (as it turns out), who are not just Catholic but very Catholic.

The intensifier “very,” in this usage, doesn’t refer to a difference in degree, but to a difference in kind. When we say that someone is very Catholic, or very Baptist, in this sense, what we mean is that this is a person who has strong opinions about Catholicism — more specifically, we mean a person who has strong opinions about other people’s faith, which they likely regard as insufficient for a whole host of reasons. The boyfriend’s mom wasn’t “very Catholic” because she attended Mass several times a week, she was “very Catholic” because she frowned on anyone else who failed to do so.

So in a sense it’s not the substance of someone’s religion that makes that person “very” religious. It’s their habit of judging the substance of other people’s religion. Those we deem to be very religious are those, in other words, who make a point of pointing out that they are very religious. Some people like to say that they are more religious than the rest of us, and the rest of us, oddly, seem to take their word for it.

We shouldn’t take their word for it, but yet we usually do.

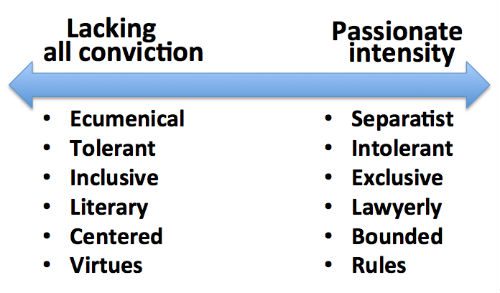

On the one hand, we recognize that their measure of religiosity isn’t the best one. We’re aware that being judgmental, touting extravagant religious totems, and constantly picking fights over the supposed shortcomings of others are not reliable evidence of healthy, credible religious devotion. But at the same time we often let them get away with this. In the Yeatsian terms we discussed the other day, we’ve allowed the worst to define for us what “passionate intensity” should look like.

Turn to any religious tradition that’s been around for a generation or more and you will find examples and exemplars from both ends of that spectrum. What you won’t find is any good reason to accept the assertion or the implication that those on one side actually possess or demonstrate a greater passion or conviction than those on the other. Yet we’ve learned to assume that’s the case. We’ve somehow got the idea in our heads that a more separatist, exclusive, bounded form of religion must involve a greater degree of devotion and commitment.

Look at the language we fall back on when we discuss violent religious conflict. It is the work, we say, of “extremists.” The peacemakers who seek to avoid or to end such violence we refer to as “moderates.” We thus grant one form of religion a presumption of authenticity and legitimate zeal, while we cast doubt on the other form, suspecting its adherents of a lukewarm, muddled “moderation.”

We often fall into this same biased language when we discuss less-violent forms of religious conflict, such as the “culture wars” here in the U.S. An anti-gay, anti-feminist or anti-science culture warrior is granted the presumption of authenticity. Any religious person who takes the opposing view is prone to being viewed as less authentic — less committed, less religious. (This is one part of why a statement endorsed by 500 mainline Protestant clergy never gets half the attention of a statement endorsed by 50 evangelical pastors.)

Again, on some level we recognize that this framework is absurd. To consider an extreme set of examples, we know that the inquisitorial obsession of Tomás de Torquemada cannot be said to represent a more authentic form of Christian conviction than the humility of Francis of Assisi. But we’re still more likely to describe the inquisitor as “extreme” or as “zealous” than we are to apply such valuations to the saint.

This is a funhouse mirror that skews our perception of religion. That, in turn, skews religion itself and the ways that religion affects the rest of the world.

This framework grants an advantage to one kind of religion over the other. One strain is rewarded with the presumption of authenticity. The other is punished with the presumption of a lack of conviction. That grants the former greater influence within the religious tradition, and greater influence in the larger society.

I’d prefer we didn’t do that.