Lisa Wade explores the long history of “the ‘benevolent sexism’ behind Dylann Roof’s racism.”

Here I want to focus on what the suspected killer, Dylann Roof, said right before he gunned down a room full of black worshippers. Reportedly, Roof proclaimed: “I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.”

It is amazing all that can be said in three little sentences.

To a sociologist who studies gender and its intersection with other forms of inequality, this statement spoke volumes.

Roof’s alleged act was motivated by racism, first and foremost, but also sexism. In particular, a phenomenon called benevolent sexism.

Wade traces the ugly lineage of the interconnection between these two ugly things, which have been intertwined in American culture — and in American religion — since 1492:

When European colonizers first arrived on the shores of America, the country was a “she”: they saw “her” as open to discovery and exploration. …

Roof is that colonizer. White women are his land. His land is a she. His relationship to this country and the white women in it is the same: both belong to white men like him.

In his mind, apparently, black people are the interlopers, the rapists, the plunderers of his natural resources, female and otherwise. It’s a twisted but not an unusual way to think about the world; not then and not now.

I read Wade’s essay shortly after reading Randall J. Stephens’ post on “Evangelicals, Fundamentalists, and Race in the Cold War Era” at Religion in American History.

Seeking to explore “how [white] evangelicals and fundamentalists engaged with politics and culture in the 1950s and 1960s,” Stephens focused on “believers’ reaction to and understanding of civil rights legislation and race relations during the high season of the Cold War.”

He studied newspapers and “evangelical and fundamentalist magazines like Eternity, Moody Monthly, King’s Business, various state Southern Baptist periodicals, Sword of the Lord, Christian Crusade, Christian Beacon, the sermons and press conferences of Billy Graham and a variety of other materials,” including “the flagship evangelical Christianity Today.”

Stephens found a range of white evangelical and fundamentalist responses to civil rights legislation. On one end of that range was the timid neutrality of Carl Henry and Christianity Today.

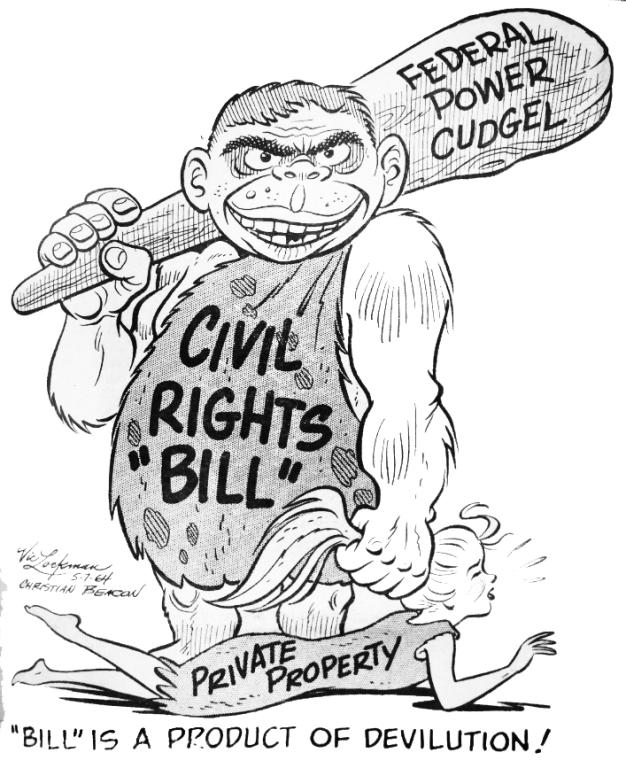

And at the other end were the multitude of viciously anti-civil-rights white Christians whose views can be summed up with this cartoon, reproduced by Stephens from the May 7, 1964, issue of The Christian Beacon. Stephens describes it as “Vic Lockman’s gendered and racialized rendering of state authority.”

And at the other end were the multitude of viciously anti-civil-rights white Christians whose views can be summed up with this cartoon, reproduced by Stephens from the May 7, 1964, issue of The Christian Beacon. Stephens describes it as “Vic Lockman’s gendered and racialized rendering of state authority.”

The Christian Beacon wasn’t a deep South publication, by the way. Its publisher was a “Bible Presbyterian” from Michigan who had relocated to New Jersey.

Lockman’s cartoon is grotesque and repugnant, but it perfectly captures the anti-civil-rights ideology of the white evangelicals and fundamentalists Stephens was studying. It exemplifies the intersection and inseparability of racism, patriarchy and wealth.

The white woman is a helpless object, one explicitly labeled “property.” The monstrous threat is a caricature of blackness — or, rather, of a white racist’s idea of blackness, an ogre that arises from the fevered imagination of fearful white men.

This cartoon was published in a “Christian” magazine — a popular publication described by its publisher as committed to an agenda of “defending the faith, exposing the apostasy, and calling Christian people to a faithful witness in behalf of the infallible Word of God.”

What does that fundamentalist word-salad actually mean? It means this cartoon. It means this hideous envisioning of precisely the diseased ideology that terrorist Dylann Roof described as he murdered nine faithful Christians at their Wednesday night Bible study.

Here in America, the racism of this ideology is pervasively tangled up with the corresponding idea of protecting the virginal purity of white women as the unsoiled property of white men. This is where purity culture comes from and where it leads back to. As Wade writes, “Our hierarchies interconnect, interweaving, providing each other with support.”