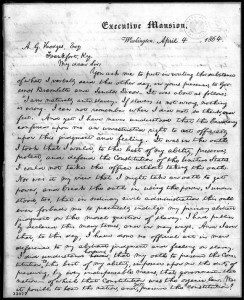

“If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong,” President Abraham Lincoln wrote in 1864. “I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.”

I can remember when I did not so think, and feel. I remember the zealous enthusiasm that swept through our white evangelical churches, transforming our faith, as we were freed of the burden of guilt and complicity and responsibility that Lincoln described because we had found an alternative. We had discovered something new that allowed us to forget the past, and to ignore the present, recasting ourselves as moral champions in a cause far greater than that of emancipation, liberation and justice.

Truly I tell you, among those born of women there has not risen anyone greater than Abraham Lincoln; yet whoever is least in this new moral cause would be greater than he.

Truly I tell you, among those born of women there has not risen anyone greater than Abraham Lincoln; yet whoever is least in this new moral cause would be greater than he.

Here was the new thing that revived and reformed and reinvented our faith. Here was the formula that erased all our past moral failings, and our ongoing moral failings, and any need to atone or account for them. Here was the “value” that would transform our understanding of our religion and of ourselves, rewriting history so that we could, at last, be on the “right side” of it. Here was the thrilling new reality that had, at last, brought about Morning in America:

“If abortion is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.”

I don’t think it’s possible to overstate what this newly discovered formula meant for us as white evangelicals. It allowed us to shrug off more than a century of disgrace, reclaiming the moral high ground — the zenith of morality — and enthroning ourselves as the indisputable guardians of the greatest moral good.

This was a tremendous relief, and it proved, for a time, to be enormously invigorating and energizing. This was exciting. We got our mojo back and we felt like we were ready to usher in another Great Awakening to take back America for Jesus and make America great again.

Before this, we had been haunted by those words of Abraham Lincoln’s: “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” Because we had been wrong about slavery. We had defended it for centuries. Our reading of our infallible, inerrant Bibles had made us certain that slavery could and should be defended, and our approach to the Bible itself came to be shaped by that desire to defend it.

“It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces,” but it had not seemed strange to us. The Bible said it. We believed it. That settled it. Slavery was biblical and we were biblical, and therefore slavery was right and good and just, and — more importantly — we were right and good and just. And from Winthrop and Whitefield on up through the birth of the Southern Baptist Convention, this was what white evangelical Christians believed about God and the Bible and slavery and, above all, about ourselves.*

Even after Appomattox, we remained largely in denial about this for another century — through the violent rejection and abandonment of Reconstruction, the generations of Jim Crow, lynching, and “sundown” laws enforced by police and by vigilantes.

Throughout all those years of refusing to admit that we had been wrong, and were still wrong — and of compounding that wrongness by failing to explore how and why we could have been so thoroughly, utterly, and monstrously wrong — white evangelical Christians sometimes tried to distract ourselves and others by changing the subject.

We did this by borrowing Lincoln’s formula: “If X is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” If we could find some other value for X — anything other than the enduring disgrace of our wrongness about slavery — then we could hope to reclaim some measure of moral credibility.

We tried Comstockian prudery for a bit. “If indecency is not wrong,” we said, “then nothing is wrong.” But while that helped for a time to allow us to reclaim the mantle of moral scolds, it never quite had enough substance to make us the moral champions we longed to believe ourselves to be. And mainly it made us the butt of too many jokes.

We had even greater success rewriting the formula this way: “If alcohol is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” This rallied white evangelicals behind a moral crusade every bit as reinvigorating as the anti-abortion crusade of recent decades. This campaign enjoyed spectacular political success — managing even to rewrite the Constitution with the Eighteenth Amendment.

Alas, that didn’t end well. And the concurrent attempt to change the subject to this formula — “If evolution is not wrong, then nothing is wrong” — didn’t really work either.

But after World War II, white evangelicals were given another chance to regain some measure of moral credibility — legitimately, and not just as a distraction or an attempt to change the subject. The Civil Rights Movement had begun in earnest with sit-ins and boycotts and voter-registration drives. Here was an opportunity for redemption. This time, having learned from our monstrous mistakes in the past, white evangelicals could step up on the right side of morality and justice.

Oops, we did it again. The majority of white evangelical Christianity not only failed to support the Civil Rights Movement, but it actively participated in the political, and often the violent, opposition to it.

White evangelical Christianity had exposed itself, again, as at best morally impotent, irrelevant and insignificant, or, at worst, as morally bankrupt and thoroughly, sinfully corrupt.

That was the state of white evangelical Christianity when I was born in 1968 and when I was born-again in a fundamentalist Baptist church in the 1970s. All we had left was the afterlife — Heaven and Hell and an otherworldly soteriology with little to say about this world, our society or our nation. So we consoled ourselves by reading Hal Lindsey books and daydreaming that we’d soon escape our enduring shame and embarrassment by being raptured off to Heaven.

But we never completely gave up trying to rework that formula. In the wake of our shameful failure to support civil rights, we flailed about trying to find something, anything, that we could plug into that formula to once again attempt to change the subject. We tried the Cold War — “If Soviet Communism is not wrong …” — but we were a bit too late jumping onto that bandwagon to pass ourselves off as the moral vanguard we needed to imagine ourselves to be. We tried endless variations of neo-Comstockian decency campaigns — “If Playboy at the 7-Eleven is not wrong …” — but this didn’t work any better than it had in Comstock’s day.

And then, finally, gloriously, we found it. Abortion. Not abortion as we’d understood it previously up until that point — as the morally significant, but still permissible termination of potential life. That was too complex to provide the clarity we needed to think, and, as Lincoln said, to feel. But what if we redefined abortion as baby-killing?

That would be a radical step — a drastic and dramatic rewriting of what we had previously taught about the status of a fetus. But the implications of that rewriting were irresistible. What if we began to say that a fetus, an embryo, a zygote — even a fertilized egg — was a person, morally indistinguishable from any infant or adult? Abortion would no longer be a complicated question best left to women and their doctors, it would become a crude question of murder — a stark, blunt, obvious moral issue on a par with … oh, yes! oh god, yes! at last! … on a par with slavery.

And thus, at last, “If abortion is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” We taught ourselves to think it and to feel it, until eventually we became unable to remember when we did not think and feel it.

And now it no longer mattered that we had been so thoroughly and monstrously wrong about slavery. Nor did it even matter that we had so recently been just as thoroughly and utterly wrong about the Civil Rights Movement. This eclipsed all of that. This would be the new paramount moral question, and this time we would be right and pure and good and all of those others — those abolitionists who had shamed us in the past and those civil rights champions who were shaming us today — would be recast as immoral baby-killers lacking in the “values” that make us special.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* #NotAllWhiteEvangelicals, of course. We still play this game — highlighting the exceptional few from the past as the true representatives of our history and pretending they were not, in fact, exceptional, and that they were not, in their time, vehemently condemned and rejected by their fellow white evangelical Christians.

Let me again recommend Donald W. Dayton’s wonderful book Discovering an Evangelical Heritage, which spotlights the honorable history of many such exceptional Christian activists — the few white evangelical voices of their time who were not wrong about slavery. Many of those stories are inspiring, but I don’t think they add up to “an evangelical heritage” as much as to a frustrating account of a road not taken, an alternate path repeatedly offered to and rejected by the majority of 19th-century white evangelicals. Many of the abolitionists Dayton profiles began as devout evangelicals but — with equal parts jumping and pushing — wound up far outside the evangelical fold, as Quakers or theological liberals or various sorts of vaguely Emersonian post-Christians.

Yes, the story of the “Lane rebellion” and the founding of Oberlin College by a bunch of abolitionist evangelicals is a terrific slice of history, but that history also has to include the way Oberlin was quickly ostracized and “farewelled” out of fellowship with the rest of white evangelicalism, pushed off from its origins to become, well, Oberlin College. The white evangelical abolitionist Jonathan Blanchard was also instrumental in the founding of what is now a well-regarded midwestern school, but today Wheaton College remains staunchly evangelical in all the ways that Oberlin is not precisely because it sloughed off every trace of Blanchardism except for his belief in temperance.

My point being that when our attempt to say #NotAllWhiteEvangelicals were wrong about slavery leads us to compiling a list of “evangelicals” that has to include people like Theodore Dwight Weld and Angelina Grimké, I think the strain of that exercise begins to show.