Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 313-315

I think that Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins would tell us that these are the most important pages of this book. This is where, they believe, they have their spokesman, Rayford Steele, “explain the way of salvation” and where they map out the “simple plan” that would allow an unsaved reader to get saved.

I find this scenario implausible. It’s difficult for me to imagine who this hypothetical “unsaved” reader might be. I can’t imagine that anyone who didn’t already believe in and agree with everything Tim LaHaye believes would still be reading at this point, hundreds of pages into the third book of the series. And I find it even harder to imagine that such a theoretical “unsaved” reader could have gotten this far and still want to have anything to do with the faith of Rayford and Buck and LaHaye and Jenkins.

But set that aside. The larger problem with this explanation of the way of salvation is that it never explains the way of salvation. We finally reach Rayford’s presentation of the gospel and find that he forgets to actually present the gospel.

I don’t just mean that he presents a distorted, stunted version of some warped, Americanized “gospel.” That’s what I expected and even, at first glance, what I thought I was seeing here. But while Rayford regurgitates several of the ingredients of that sort of gospel message, he never puts them together into any meaningful whole. He never tells us about this “simple plan.”

Buck never ceased to be moved by what Bruce had always called “the old, old story.”

The reference there is to “I Love to Tell the Story,” an old gospel hymn based on a poem by Katherine Hankey. The song contains some lovely lines — “And when, in scenes of glory, I sing the new, new song / ‘Twill be the old, old story, that I have loved so long” — but it’s notable mainly for its ironic refusal to ever actually tell the story that it tells us it loves to tell. “I love to tell the story, for some have never heard,” it says, “the message of salvation, from God’s own holy word.” But if any of those poor benighted souls who have never heard this message were to hear this hymn sung a dozen times over they would still have never heard that message.

This hymn, in other words, is about “the message of salvation,” but it does not itself contain or convey that message. It tells us that telling the story is important, but it never tells that story itself.

Here again, I think, we get a glimpse of the way that Bad Writing and Bad Theology intersect. The telling should serve the story, not the other way around. There’s a danger, I think, when we start loving to tell the story more than we love the story itself.

In Hankey’s defense, though, her poem at least hints at the general gist of this untold story. It is the old, old story, she says vaguely, “of Jesus and his love.” That’s far more substantial than anything we find in this chapter from Rayford, LaHaye and Jenkins. Their discussion of this old, old story scarcely mentions Jesus — only in passing, as the scapegoat for our sin problem. And it never, ever mentions love. Love seems to have nothing to do with it.

So what’s left of this old, old story if we take away Jesus and his love? Not much. And not a story at all, really. Or a simple plan or an explanation of any way of salvation.

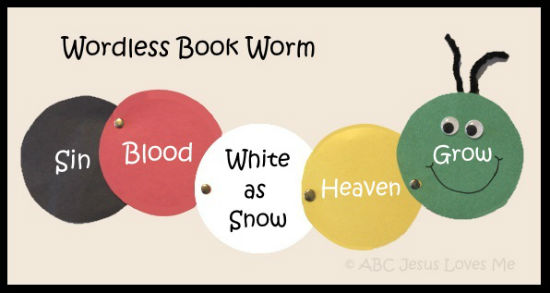

What we find here, instead, is more like poor Rayford trying to retell an old joke that he doesn’t quite remember correctly. That joke seems to be something like the version of the “gospel” you might hear from someone following one of those pop-evangelism methods like the Wordless Book or the Navigators’ “Bridge” diagram or the “Romans Road.” He references bits of all of those here, and those references are so familiar to white evangelical readers that we instinctively fill in the rest of the story the way we’ve heard it a thousand times before. We knew the original joke so well that we imagine we’ve just heard it repeated again, even though Rayford botches the set-up and then forgets the punchline.*

Rayford’s bungled presentation of “the way of salvation” starts with an emphatic rejection of what he says it’s not. The Christian gospel, Rayford Steele says to a church filled with Christians, “has been the most misunderstood message of the ages.” And he takes great pains to ensure that any pre-Council of Trent medieval Catholic princes in his audience don’t misunderstand the “simple plan” of salvation as having anything to do with the buying and selling of indulgences.

“Had you asked people on the street five minutes before the Rapture what Christians taught about God and heaven, nine in ten would have told you that the church expected them to live a good life, to do the best they could, to think of others, to be kind, to live in peace. It sounded so good, and yet it was so wrong. How far from the mark!”

This is a major theme in the Left Behind series — denouncing the menace of “works righteousness” or “salvation by works.” See for example, way back in Tribulation Force, where Buck gets into a theological argument with an evil Catholic bishop over the meaning of Ephesians 2:8-9, “Skipping Verse 10.”**

Rayford is concerned that nine out of 10 people misconceive of the “way of salvation” as having something to do with earning one’s way to Heaven through good works, so he starts off with a barrage of proof-texts to hammer home the point that everyone is a miserable, God-damned sinner who deserves only calamity, death, and eternal torture in Hell:

“The Bible is clear that all our righteousnesses are like filthy rags. There is none righteous, no not one. We have turned, every one, to his own way. All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. In the economy of God, we are all worthy only of the punishment of death.”

This is the Gospel According to Linda Ronstadt: You’re no good, you’re no good, you’re no good, baby, you’re no good.***

Again, this is familiar stuff for evangelical readers who’ve just been told that they’re about to read an evangelistic sermon. Some happier renditions of the old, old story start with “Jesus and his love,” or with John 3:16, or with “God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.” But Rayford seems to prefer the version of the story that starts with sin and damnation. He starts with the sin-and-death page of the Wordless Book, and with the chasm of sin separating us from God in the Bridge illustration. He explicitly cites the first few verses of the “Romans road,” reminding us that “all have sinned” and that “the wages of sin is death.”

But then he turns aside from this Romans Road — never getting to the bits where it suggests the possibility of salvation. Rayford forgets all about “God proves God’s love for us in that while we were yet sinners …” and about “No one who believes in him will be put to shame.” He sketches out the unbridgeable chasm, but never really draws in the cross that bridges it. He forgets that the Wordless Book has a bunch of other pages.

Here’s the conclusion of Rayford’s evangelistic message. Here is his explanation of “the way of salvation”:

“I would be remiss and would fail you most miserably if we got to the end of the memorial service for a man with the evangelistic heart of Bruce Barnes and did not tell you what he told me and everyone else he came in contact with during the last nearly two years of his life on this earth. Jesus has already paid the penalty. The work has been done. Are we to live good lives? Are we to do the best we can? Are we to think of others and live in peace? Of course! But to earn our salvation? Scripture is clear that we are saved by grace through faith, and that not of ourselves; not of works, lest anyone should boast. We live our lives in as righteous a manner as we can in thankful response to the priceless gift of God, our salvation, freely paid for on the cross by Christ himself.

“That is what Bruce Barnes would tell you this morning, were he still housed in the shell that lies in the box before you. Anyone who knew him knows that this message became his life. He was devastated at the loss of his family and in grief over the sin in his life and his ultimate failure to have made the transaction with God he knew was necessary to assure him of eternal life.”

Rayford loves to tell the story about how Bruce loved to tell the story, but he’s still not actually telling us the story. It has something to do with Jesus having “paid the penalty” (for our sins, presumably). And that means “the work has been done … on the cross by Christ himself.” But that work is also apparently insufficient. Some essential work remains — work that we must do ourselves. We have to “make the transaction with God.”

What does that entail? Rayford doesn’t say. We can guess here that — despite all the pseudo-Calvinism of his introductory screed against works-righteousness — it requires some kind of decision for Christ and the recitation of the magic words of the sinner’s prayer.

But we can only guess, because Rayford never says. He forgot the punchline. He forgot that there’s supposed to be one.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* There’s an old joke about a bunch of people stranded on a desert island and the only book they had was an old joke book. Eventually, everybody had read it so many times that they had it memorized, so nobody bothered telling the actual jokes anymore, they’d just cite the page number. “Page 14” someone would say, and everyone would laugh.

“Page 137,” someone else said, and one guy really lost it, just laughing and laughing hysterically. “I never heard that one before,” he said.

“Page 228,” someone said. Silence. Nothing. Some people can tell ’em, and some people can’t.

Anyway, that’s kind of how this section of Nicolae reads for its evangelical audience. There are enough of the ingredients of a standard evangelistic sermon here that we respond as though we’d heard the full joke and not just the page-number. But Rayford never actually tells the whole joke we imagine we’re hearing. And he gets the page numbers wrong.

** What we discussed there applies here to Rayford’s pseudo-Reformed anti-works “gospel” as well, so let’s revisit a bit of that:

Martin Luther believed in the doctrine of grace. Buck, LaHaye and Jenkins believe in believing in the doctrine of grace. The archbishop of Cincinnati did not believe in that doctrine, and so he was left behind. Pope Calvin was raptured along with all the other RTCs because he had come to believe in the gospel of salvation by belief in the proper understanding of the mechanics of salvation. RTCs are not real, true Christians because of the grace of God — they are real, true Christians because their sentiments are aligned with the correct side of the argument about the role of God’s grace in salvation.

What L&J and Buck are arguing for here is self-refuting nonsense that swallows its own tail and it isn’t easy to give a lucid description of such madness, but try thinking of it this way: They do not believe in Calvinism, but in Calvinism-ism. They believe that we achieve our own salvation by means of asserting that Luther, Calvin and Augustine were correct to say that we cannot achieve our own salvation. The logical implication of this would seem to be that Heaven will be populated with Calvin-ists and Luther-ans, but that Calvin and Luther themselves will be excluded. Those reformers mistakenly believed that God’s grace would be sufficient to save them, not realizing — as L&J do — that God and grace are powerless apart from what really matters, which is our own assent to the proposition that grace is sufficient. To be saved, then, we need to say that God’s grace alone is sufficient, but to mean by that that our belief in the power of our believing that we believe that is what is really sufficient to save us. Or something like that.

The point is that it is the authors and their mouthpiece who are here rejecting the doctrine of grace. The gist of that teaching is that God’s grace is not dependent on our merit or worthiness — that’s what “grace” means, after all. But the authors believe God’s grace is dependent — that it is earned and not freely given. They believe grace is dependent on a correct understanding of grace, that it is contingent on whether or not its potential recipients can properly articulate how it works. They believe, in other words, in righteousness by works — but mental, or sentimental, works, rather than tangible ones.

*** Rayford is quoting here from Isaiah, Romans, and the Psalms. The Isaiah passages have to be bent and twisted to apply to Rayford’s point. The ones from Romans need to be excised from the context of that letter’s larger argument. This isn’t to say that “the Bible is not clear” that we are all sinners, but that this doesn’t necessarily mean what Rayford’s garbled, unfinished gospel suggests.

Here it’s important to remember that the word our English Bibles like to translate as “righteous” or “righteousness” is the same word that is better, and more precisely, translated elsewhere as “just” or “justice.” This is another place where that makes a big difference. “There is none who is just, no not one” means and entails something very different from “There is none righteous, no not one.” Or think of the vast difference in how we perceive the message “repent of your sins” versus “repent of your injustice.”

The prophet, psalmist and apostle quoted by Rayford were all explicitly concerned about justice and injustice, but that’s gotten lost in translation.