At Patheos’ Anxious Bench blog, Philip Jenkins continues to serve up big helpings on one of my favorite subjects: the interplay between urban legend, folklore and pop culture, and how all those things come to influence and to shape what we think we know about history. Or what we think we know generally.

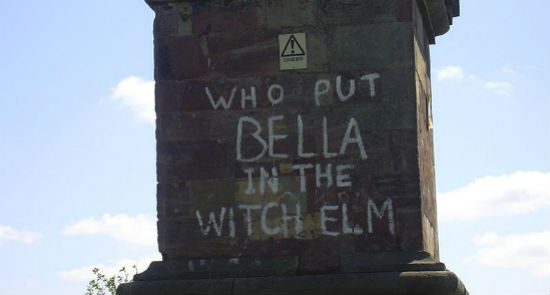

In his latest installment, Jenkins looks at “The Black Dog and the Wicker Man,” and the fantastic stories that circulated around a 1945 murder in the English countryside. “It’s a large saga with huge resonances in popular culture,” he writes, “so I will sketch it briefly here. It’s suggestive about the making of wholly bogus modern legends, and how they come to be believed as sober fact.”

It’s just the sort of thing that might send you off on a Google rabbit trail, reading about Bridget Cleary and Inspector Robert Fagin and “witches Sabbaths” and witch killings and the once-popular novels of Dennis Wheatley.

That can be fascinating and a lot of fun and an entertaining waste of time. But it’s also not entirely a waste of time. These “wholly bogus modern legends” and stories and tall tales matter. They inform us, and misinform us, and they inform how we hear and understand other stories, including true stories grounded in documentation and facts.

Someone murdered Charles Walton in 1945, and police never figured out who that was. But there were stories and rumors — stories and rumors based on other, earlier stories and rumors, with enough layers of mutually reinforcing lore that, even without intending to, people wind up believing there must be something to all of that.

So over here, way off to one side, you’ve got the novelist Wheatley, mining legends and folklore, embellishing it and repackaging it all in an updated variation. He sells a lot of books and his stories become widely known — become something that people know, and therefore something that people expect to see, and imagine they do see, in the world around them. Add in some attention-hungry pseudo-academics, tabloid sensationalism, and a headline-chasing public official and what started as a “wholly bogus urban legend” appears to many to be confirmed as fact.

This makes life difficult for a historian, like Jenkins, who’s trying to sort out what actually happened — including that part of what actually happened involved widespread misapprehension and the acceptance of misinformation.

The same challenge Jenkins is tackling here faces any Christian who attempts to consider what is widely and popularly believed to be the Christian doctrine of Hell. It’s almost impossible for us today to talk about — or even to think about — any idea of Hell that isn’t thoroughly intertwined with and shaped by a host of folklore, legends, pop-culture storytelling, tabloid sensationalism, and pseudo-academic malarkey that’s every bit as weird and bogus as the belief that poor Charles Walton was ritually sacrificed in 1945 in a “witch killing” intent on ensuring a bountiful harvest.

Oh, but the Bible talks about Hell! It’s biblical!

No. It really, really is not. The Bible mentions a word that our English translations present as Hell. We read that word not just in translation, but filtered through centuries of agglomerated lore and legend and sheer Barnum-esque razzle-dazzle. We then take all of that — legends, speculative nonsense, Dante and Bosch, Tundal and the Gospel of Nicodemus, medieval morality plays, Orpheus and Persephone, Buffy and the Winchester brothers, Danzig and Dio, Billy Sunday and Mike Warnke, Charisma and Weekly World News — and we carry it all with us as we read that English word “Hell” in our Bibles, finding there in that biblical word everything we’ve learned to expect in it.

But that’s not what it actually says. And none of that is really there for the finding. It’s only there, in the Bible, because we’ve carried it with us and put it there.