Originally posted February 2, 2007.

Read this entire series, for free, via the convenient Left Behind Index. This post is also part of the ebook collection The Anti-Christ Handbook: Volume 1, available on Amazon for just $2.99. Volume 2 of The Anti-Christ Handbook, completing all the posts on the first Left Behind book, is also now available.

Left Behind, pp. 249-250

The Antichrist has begun his evil plot and stands poised to take over the United Nations, and then the world, so I know what you’re thinking: How will Rayford and Chloe get both cars back from the airport?

Fortunately, our authors are one step ahead of you, and they return here to what they do best: exploring the logistics of suburban travel.

Rayford’s plane touched down in Chicago during rush hour late Monday afternoon. By the time he and Chloe got to their cars, they had not had the opportunity to continue their conversation. “Remember, you promised to let me drive your car home,” Chloe said.

“Is it that important to you?” he asked.

“Not really. I just like it. May I?”

Ugh, rush hour traffic is never fun. On the bright side though, since the Event, there’s probably a lot less traffic even during rush hour — especially out toward Wheaton. And the Steeles won’t have to worry about getting stuck behind a school bus ever again.

This whole scene plays out as though the Event had never occurred. Rush hour this Monday afternoon is portrayed as exactly like rush hour the previous Monday, before the disappearances, the plane crashes, and the global empty nest. Rayford and Chloe see nothing remarkable on their walk from the gate to the parking area, not even a hint of debris, or broken glass, or chalk outlines.

Rayford is a protective father — he checks to make sure his BMW has a full tank before letting Chloe drive it home. But he has no qualms about letting her drive around alone, no worries that this might be unsafe in the lawless Sin City of post-Rapture Chicago.

Everything seems eerily normal. “You’ll beat me home,” Rayford says. “Your mother’s car is on empty. … I think I’ll pick up a few groceries while I’m out.”

Normal supplies of gas and groceries seem to have continued, uninterrupted, without shortages or price gouging. The Event’s ultimate impact on day-to-day life seems like something less than a Gulf Coast hurricane or a substantial snowstorm

Suddenly remembering that no one has talked on the phone for almost a dozen pages, Rayford retrieves his car phone before his daughter drives off.

“… Just let me get my phone out of it. I want to see when Hattie can join us for dinner. That’s all right with you, isn’t it?”

“As long as you don’t expect me to cook or something sexist and domestic like that.”

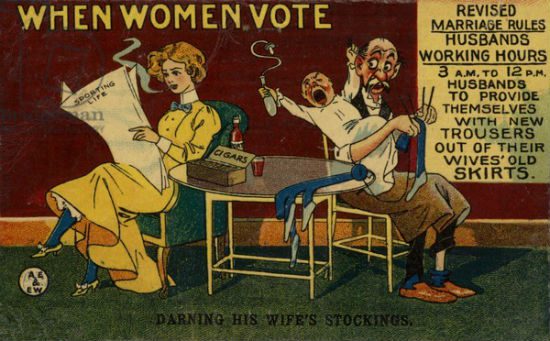

Because, you see, Chloe is a feminist, and this is how LaHaye and Jenkins imagine feminists talk.

Chloe, I suppose, picked up feminism while she was away at college (she certainly didn’t learn it at home). This is what happens when you send your children to evil, secular institutions like Stanford. The intended lesson is to remind readers that the only way to prevent such brainwashing is by sending your children, instead, to a good, godly institution, like Bob Jones or Liberty or your local church’s preferred unaccredited Bible College.

It’s a bit odd that Chloe’s feminism hasn’t surfaced before. She was angry over her father’s creepy relationship with a young flight attendant, but never on feminist grounds. And she doesn’t blink an eye when the New Hope Church offers her dad a leadership role after his second visit — something that was never offered to her devout mother during her many years of faithful attendance.

No, the only time her feminism surfaces is when she thinks she might be asked to cook — something L&J seem to think no feminist would do (apparently they either eat out or starve). The word they use here is “domestic” — as in related to the home. Chloe the feminist hates the home because, for L&J, feminists are homewreckers.

Keep in mind that Tim LaHaye’s wife Beverly runs Concerned Women for America, the largest anti-feminist organization in the country. Combating the anti-domestic agenda of feminism is a major activity for the LaHaye household. You’d think that after decades of such activity, LaHaye might actually have some idea of what these feminists look, sound and act like.

But he has no idea. He doesn’t know how they talk, what they think, what they want. Chloe can’t even be called a caricature of a feminist. Caricatures are drawn with intentionally exaggerated features based on reality. The distorted picture L&J draw of a feminist is not based on reality, and it’s not intended as an exaggerated parody. It’s an accurate picture of what they imagine feminists are really like.

You see this again and again in Left Behind wherever the authors are forced to describe in particular the things they obsessively fear and oppose — whether it’s feminism, the United Nations or “the media.” For all of their preoccupation with these things, they have no idea what they actually look like.

“As long as you don’t expect me to cook or something sexist and domestic like that.” Feminists don’t talk like that. Humans don’t talk like that.

It’s also more than a bit odd here that this is Chloe’s only objection to the strange evening Rayford has planned. Her father is inviting over this woman, only a few years older than herself, in the hopes that her physical attraction to his own sexless lust will allow him to explain to her about the tenets of the religion to which he converted just days ago himself.

According to L&J, feminists don’t like to cook, but they’re fine with The Most Socially Awkward Scenario of All Time.