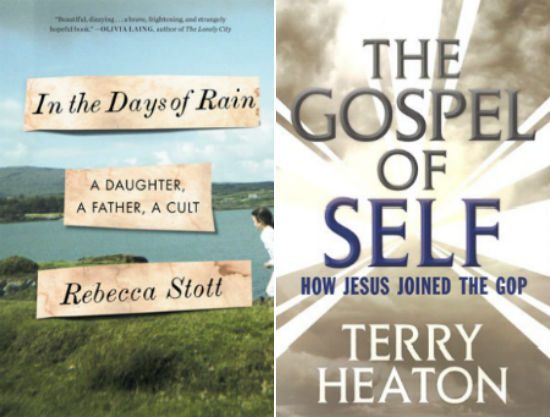

Rebecca Stott talked with National Public Radio this weekend about her new memoir, In the Days of Rain: A Father, A Daughter, A Cult.

The word “cult” is often misapplied, but Stott’s use of it there seems precise and accurate. She was raised in Brighton, England, among the Exclusive Brethren — a horror-show separatist sect that spun off from the Plymouth Brethren in the 19th century. “They believe in the Rapture,” Stott explains. “They believe that they alone will be taken off the planet, and unless they stick to Brethren rules and have no contact with the outside world that they’ll be left behind in the Rapture. … They’re very conservative, very secretive, very separatist.”

The sect maintains a fierce control over its members by enforcing a comprehensive set of rules — many of which seem arbitrary, considering the group’s claim to be biblical literalists: “You couldn’t eat with non-Brethren outside; you couldn’t have wristwatches, pets; you couldn’t go to the cinema or have radios or television or newspapers. So everything was Brethren-centered. … Everyone was being watched by everyone else. There’s a lot of mass confessions; there were a lot of punishments for non-compliant behavior.”

To be clear, the Exclusive Brethren are extreme. They’re way, way out on the fringes of evangelical Christianity. But this extremity is a difference of degree, not of kind. Most “mainstream” white evangelical Christians would be horrified to read Stott’s description of her life among the Exclusive Brethren, but it won’t strike them as wholly alien, only as a more intense distillation of ideas and practices that will be all-too familiar.

That’s particularly true, I think, when we get to the bit where Stott describes what her experience has meant for her relationship with the Bible:

I still cannot open the Bible without hearing the sound of those men using scriptures almost like rapiers with each other, you know, or trump cards. They knew the Bible so inside out, so they would use one scripture to trump another and it was all men locking horns, you know, or antlers. And so it’s hard for me having had so many hours of that not to see the Bible as a place, you know, full of words that have been used for warfare.

Being forbidden to have pets? That seems weird and strange. Disintegrating the Bible into clobber-text trump-card verses to be used like weapons in a never-ending duel? That’s something most evangelicals will recognize.

The 700 Club isn’t as far out there on the fringes of white evangelicalism as the Exclusive Brethren. Pat Robertson’s strange stew of faith-healing, fund-raising, culture-warring and conspiracy theorizing may be pretty far out there, but his television “ministry” is an established institution not far from the center of mainstream American evangelicalism. Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network influences, and is supported by, millions of American evangelicals. Sure, the faculty-lounge evangelicals on Christianity Today’s editorial board might find Robertson tacky and doctrinally sloppy, but his audience is far bigger than theirs.

So we can’t dismiss Robertson as an anomaly or a “cult” that can easily be walled off from the rest of American evangelicalism as a separate category.

Terry Heaton, a long-time producer at CBN and The 700 Club, has also written a memoir of sorts. But while the world of American evangelical broadcasting may be very different from the world of Exclusive Brethren in England, his story also parallels the story Rebecca Stott tells. Elizabeth Bruenig wrote about Heaton’s new book, The Gospel of Self: How Jesus Joined the GOP, for the Washington Post: “When the evangelical life is trouble for the soul.”

The tragedy that emerges in The Gospel of Self is what Heaton’s immersion in Robertson’s politicized Christianity did to his own newfound faith. “Little did I realize at the time how [fighting the culture wars] dramatically weakened my/our beliefs in the capabilities of an almighty God,” he writes.

… Robertson presented himself as a shepherd of souls, but in his quest for temporal power, he led his flock astray and left their faith to wither. This isn’t the story one usually hears about the rise of the religious right, but for Christians, it is perhaps the more important one.

The main difference between Pat Robertson and the leaders of the Exclusive Brethren cult may just be one of scale. The elders of the Exclusive Brethren promoted a toxic, weaponized Christianity in order to control the lives of their flock. Robertson is thinking bigger — designing his toxic, weaponized Christianity in an attempt to control Washington, DC, and thus an entire country.