Here’s another theological morsel to chew on from David Congdon.

The ones who can be most secure in God’s saving presence are those without any worldly or spiritual security, those abandoned by both secular and ecclesiastical powers, those sacrificed on the altars of history for the “higher goods” of civilization and Christendom. The real question is not whether non-Christians are saved, but whether Christians are saved. If they are, it is only insofar as they put their Christianity at mortal risk, ready to abandon every security in order to find their security in God alone.

Congdon’s framework is exciting for Barthian types like the folks at DET, but its beyond “controversial” for most evangelical types. As he notes, the book in which he argues this case — The God Who Saves — cost him his job. He’s not bitter about that — the “farewell” was mutual here.

But I hope that evangelical folks won’t just tune out everything Congdon is saying here just because he no longer believes in the conscious afterlife of Heaven or Hell that they regard as an essential core belief. I’d ask them to heed what he’s saying above and apply that within their own framework of a conscious afterlife and a “literal” Heaven and Hell.

I don’t mean his attempt “to explain how a universalist soteriology was possible on systematic theological grounds.” Nothing that high-falutin and sophisticated. I’m talking about a good old-fashioned chapter-and-verse exploration in the time-honored evangelical tradition of concordance-driven word-searching Bible study. It will likely prove to be unsettling.

Because here’s the thing we evangelical types aren’t allowed or accustomed to notice: Most of the time in the actual Bible, the poor are already saved. All of them. They just are.

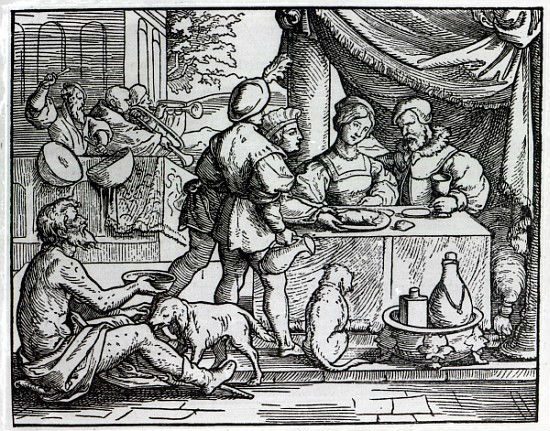

That’s a given. It’s rarely stated outright because, throughout the actual Bible, it goes without saying. It is simply assumed — over and over again. The starkest example of this might be Jesus’ parable of the rich man (sometimes called “Dives”) and the beggar Lazarus. How and why is Lazarus “saved” in that story? He just is. Salvation belongs to him because nothing else does. The only drama in that story involves Dives and his wealthy relatives. Can they be saved, too? Yes — because they need to be. No such need is attributed to Lazarus.

But surely Lazarus — like all people — is a sinner. And surely that means he needs to be saved from his sins? Probably so. But if his Jubilee and salvation also involves the forgiveness of his sins, then it doesn’t occur in that story due to his confession and repentance. It is granted to him and attributed to him because he is a beggar. That’s how Jubilee works. It makes demands from creditors and extends grace to debtors — whether or not they seek it or even know it.

Or consider the parable of the Sheep and the Goats, in which the nations and the people of the nations are judged based on how they respond to the hungry, the naked, the sick and the imprisoned. Some of these folks are “saved” and some are not, but there’s a whole other category unaddressed in this judgment — the hungry, naked, sick and imprisoned themselves. They seem exempt from the summons to stand before the throne. There’s no sense questioning whether they meet the standard of this judgment because they are the standard. Their “salvation” is never in question. The only question is who from among the rest of us will be joining them. (And the answer, in that parable, is those who have already joined them.)

One of my favorite early Christian texts is, like Congdon’s book, an exploration of soteriology that caused great controversy in its day. In “Who Is the Rich Man Who Is Saved?” Clement of Alexandria offered the then-startling suggestion that salvation might be possible for some wealthy people. This was a contested idea at the time. But the point here is not whether Clement’s argument was right or wrong. The point here is what was not being argued by Clement or his disputants — the thing they all agreed on and assumed and didn’t even need to bother stating. There didn’t need to be a corresponding text titled “Who Is the Poor Person Who Is Saved?” because everybody Clement knew already knew the answer: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.”

There are, of course, plenty of other soteriologies that we can find in our Bibles, many of which seem to have nothing to do with matters of wealth and poverty. But one could make a case that these various plans or paths of salvation(and they do vary, surprisingly, quite a bit) do not supplant or negate that basic premise of Lazarus and Dives. Their discussion of a need for salvation certainly seems to apply to Dives — and to me — but I’m not sure they apply to Lazarus. It’s possible that Lazarus, in any of those frameworks, doesn’t need to get saved, because salvation already belongs to him.