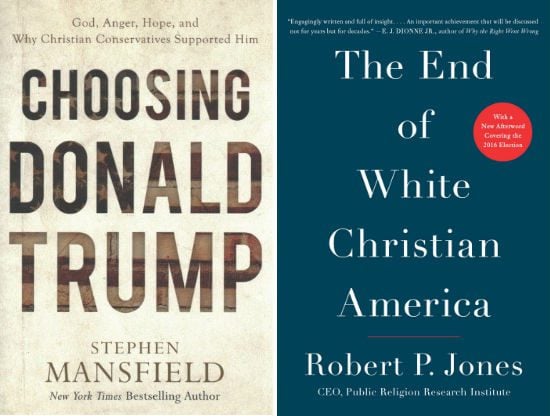

Author Stephen Mansfield has some perceptive things to say about the 81 percent and the current state of white evangelicalism in this interview: “After ‘Choosing Donald Trump,’ Is The Evangelical Church In Crisis?”

They are in crisis. And I think there’s a lot of healing that needs to happen. I mean, I know of large families that have met for Thanksgiving dinner and didn’t meet this last Thanksgiving, and the dividing issue that brought strife was the Trump presidency. I know churches where there have been splits. I know of tension on church staffs.

There’s a great deal of turmoil, and evangelicalism as a whole is in flux, and a lot of it has to do with politics. I know many people who are saying, “I’m not sure I’m staying in the church that I’ve been attending because it’s become so political.” I have heard that phrase probably two dozen times.

So evangelicalism as an approach to Jesus and an approach to wanting to convert the world is fairly solid, but evangelicalism as a political movement is definitely in crisis. I think it’s caused a lot of people to rethink what they’re doing, what they’re connected to, what kind of church they want to be in. And I think that’s going to continue for quite a while.

It’s a tragedy. In fact, if you say the word evangelical to those outside of evangelicalism, they assume it’s a political movement, and that’s part of the problem. They don’t know that it’s more because that hasn’t been the public face of evangelicalism.

“Healing” is very much the wrong word and the wrong idea. There’s a lot of repentance “that needs to happen,” with the full complement of all that entails — remorse, confession, apology, restitution, penance, transformation. “Healing” may be a consequence of such repentance, but will be impossible without it.

I also think Mansfield is overly optimistic when he says that “evangelicalism as an approach to Jesus … is fairly solid.” He’s trying to distinguish there between the enthusiastic, lock-step partisanship of the religious right and the less overtly politicized white evangelicalism of the old “mainstream” — the Christianity Today crowd, the NAE, or even the “above the fray” white evangelical folks in the Books & Culture or Image crowds.

It’s true that these “mainstream” white evangelicals were never explicitly a part of the religious right, and that they’ve always been somewhat uncomfortable about their more vocal and activist brethren. But they’ve never been substantially opposed to it either. They’ve lamented its tone, but never its message or its agenda. (It’s a bit like the Jeff Flake problem — good speech, a year too late, but the senator still votes with Trump 90 percent of the time.) While this white evangelical “mainstream” may have chosen to stand at a (slight) distance from the more aggressive religious right, they’ve never distanced themselves from its goals and aims. And even if they have only stood by, they have always been the nearest bystander — the group whose inaction and silence is most responsible, as a sin of omission, for allowing the religious right to thrive, unchallenged, and to gradually redefine evangelical Christianity as nothing more than the politics of white resentment.

Just look at the phrase Mansfield uses to attempt to describe any form of white evangelicalism that might exist separately from this partisan political movement — “evangelicalism as an approach to Jesus and an approach to wanting to convert the world.” A generation ago, the iconic representative of that approach was Billy Graham. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association is now run by Franklin Graham — a Trump-loyalist since 2012 whose Facebook posts read like something Milo’s ghostwriters cooked up for Steve Bannon at Breitbart. This Christmas, thousands of “mainstream” white evangelical churches will stuff shoeboxes with presents for Franklin Graham’s Operation Christmas Child, because years of venomous hate speech from Franklin has done nothing to cause them to question the legitimacy of his politicized “gospel.”

Mansfield is correct that the religious right has become “the public face of evangelicalism,” but the supposedly different evangelical “mainstream” has the same face. It wears a slightly different expression, perhaps, but it’s the same face. That’s where that infamous 81 percent comes from. Their gospel of salvation is the same, and it involves doing whatever it takes to stock the bench with Federalist Society drones. Not-Garland is their personal lord and savior.

Another point on which I think Mansfield is mostly right comes in his discussion of how the Trump-era crisis — or, rather, the Trump-era unmasking of the pre-existing crisis — affects the possibility of white evangelical outreach to younger generations and to people of color. He says:

I think that they are especially going to lose influence amongst Millennials, who are strongly social justice-oriented, and the surveys indicate that the vast majority of them are very suspicious of Donald Trump.

You’ve got an unusual situation here where the leaders of the religious right are not only having to account to a watching world for why they compromised their religious message to support Donald Trump, but you also are going to have some blowback from the very people that the religious right is trying to reach. The very people these pastors are trying to reach — the young, people of color, etc. — I think they may have lost them and, in some cases, permanently.

When I say I think this is mostly right, what I mean is that I think it is partly wrong. Mansfield is certainly correct to say that lock-step submission to the agenda of the religious right, resulting in overwhelming support for Donald Trump, is disastrous for white evangelical outreach efforts “trying to reach the young, people of color, etc.” And they do, in fact, talk a great deal about their desire for “outreach” to such others. White evangelicals have long agreed that it would be really terrific if they could find a way to persuade young people and people of color to join their ranks, to fill their pews, and to increase their numbers.

But it overstates the case, misleadingly, to take this desire for such successful “outreach” at face value as a meaningful attempt to actually do it. They want to “reach the young, people of color, etc.,” but they’re not “trying to” do it. Every such try eventually balks at the realization of what that might entail.

OK, maybe “every such try” may be too categorical. Very rarely, some such desire for outreach leads some local congregation or group to come to grips with what it would actually entail and they don’t balk. But as a result, they soon become categorized as “controversial” or as “post-evangelical.” Their evangelical identity and membership is rescinded because the rest of the tribe — accurately — regards them as no longer a part of white evangelicalism. Farewell!

My own experience with this on the receiving end involved being the focus of such “outreach to Millennials” back when it was “outreach to Gen-Xers.” What that meant was, more or less, that we’d be allowed to wear flannel when we sat quietly, unquestioningly, in the pews, assenting to otherwise think and act just like everyone else was told and expected to think and to act.

The alleged attempted outreach to Millennials and to people of color work the same way, just with different sets of dismissively stereotypical details substituting for flannel shirts.

So yes, in a sense, Millennials and people of color are “the very people these pastors are trying to reach,” but what that amounts to is that they’d love to see an influx of younger people and people of color reversing the ebbing numbers of their graying flocks, but only if those newcomers abandon whatever their own concerns might be and agree that the paramount meaning of the gospel involves the overturning of Roe v. Wade and of Obergfell v. Hodges and Griswold v. Connecticut and Brown v. the Board of Ed and West Coast Hotel v. Parrish.