It’s 2018 and respectable publications are running scads of think pieces on the meaning of “evangelical” that read like the archives of this blog from 2004. It’s nice to see folks catching up.

This piece from the Christian Science Monitor’s Harry Bruinius is typical of this now-thriving genre, “In Trump era, what does it mean to be an evangelical?” Bruinius does a good job identifying some of the more perceptive scholars of American evangelicalism — George Marsden, Tim Gloege, Randall Balmer — and letting them speak in his piece.

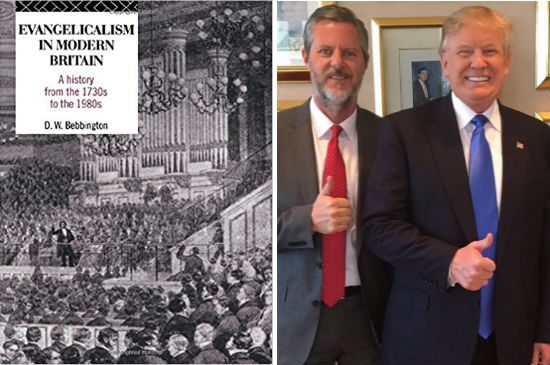

Bruinius misspells “Bebbington,” which is kind of wonderful since it spotlights the weirdness of allowing a four-part description intended for Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: 1730-1980 to become the procrustean framework for understanding white American Protestantism in the 21st century.

That’s why I think Kristin Kobes Du Mez — a history professor at Calvin College — offers the most clear-eyed answer to the question posed in the piece’s title. She isn’t trying to force her description to fit into the typology Bebbington created to describe 18th-century Bible Christians in England. Nor does she get trapped in the standard — and in some ways misleading — narrative of Scopes-Henry-Falwell sketched out earlier by Bruinius. Dr. Du Mez simply reminds us what it is that we’re looking at today in America when we look at this thing called “evangelicalism”:

“It’s hard to talk about modern, 20th-century American evangelicalism without putting race at the center,” said Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “It’s not just a pure doctrinal matter.”

If people identify as being born again or as an evangelical, this means something to them, she said. And in addition to faithful church attendance, there’s also what she calls a “culture of consumption,” of popular evangelical media, books, movies, and music, often promoted by television personalities.

“I look at the last half century of American evangelicalism, I find as a defining feature the desire to claim cultural power,” Du Mez said. “And along with that comes a Christian nationalism.”

We can tease that into a “quadrilateral” that seems far more apt, valuable, and insightful for anyone attempting to say what it means to be an “evangelical” in America in the Trump era (or, for that matter, in the George W. Bush era).

1. Race is at the center.

2. Doctrine is secondary.

3. Membership in a market-driven consumer subculture.

4. Driven by a desire to claim cultural power.

This better-fitting quadrilateral helps to explain the True Scotsmen shenanigans and shifting weights and measures currently getting tossed around in an effort to defend some imagined Platonic ideal of evangelicalism from the observed reality of its lockstep association with Trumpism and W’s M.D.

The “desire to claim cultural power” requires evangelicalism to be defined as broadly as possible to make the numbers seem massive, powerful, and deserving of hegemonic control. So everybody who can be claimed as vaguely Bebbington-ish gets included — from Trump-worshipping court evangelicals like Jeffers and Falwell and Paula White, to all the black and Latino “evangelicals” otherwise excluded from the consumer subculture and from ever having a “seat at the table.” But when that close association with Trumpism diminishes all pretense of evangelical moral authority — thereby threatening its bid for cultural power — the lines have to be redrawn to exclude the previously included court evangelicals and Charismanews whackaloons. And all of those non-white “evangelicals” who get included when the push for cultural power requires bigger numbers also get excluded every other November because they fail to vote as they’re told by evangelical gatekeepers.

Bruinius gives the final word to another history professor, Bill Svelmoe of St. Mary’s College (Indiana), who describes himself as a former Republican and (therefore, by necessity) a former evangelical:

“What happens is, as you plant your flag over the Republican Party as the party not just with the right ideas about abortion, or even ideas about the economy, it becomes the moral party, God’s party,” Svelmoe said. “And now you have to defend everything with a religious fervor. And the folks on the other side are now your enemies, they are on the devil’s side.”

Svelmoe names the defining feature of American evangelicalism that might, at first, seem to be missing from the quadrilateral I’ve borrowed from Du Mez: abortion politics. But look again. Abortion politics is present in every one of those four distinctives — present as both expression and excuse.