(Originally posted in 2015. If I were updating this, I’d probably add Thomas Nast’s illustrations and the famous “Yes, Virginia” editorial to the list of canonical Santa lore. And I’d clarify that our task isn’t so much to reconcile the conflicting aspects of the Santa canon as to understand what is being said, and why, in those differences. A harmonized Santa canon would be as beside the point as those awful “harmonies” of the Gospels.)

The mythology of Santa Claus is a mess and we need to sort some of that out.

I don’t mean the implausibilities and physical impossibilities of our Santa stories. Those don’t pose any problem that can’t be hand-waved away with an appeal to magic.

How does Santa visit every child’s home in one night? Magic. How does he fit all those toys into one bag or sleigh? Magic.* How do reindeer fly? How does he fit down the chimney? What if there isn’t a chimney? Magic, magic, magic. Duh.

Every year we get a new crop of whimsical science-of-Santa articles attempting to calculate what Santa’s magical journey would entail when it comes to the laws of physics. This is beside the point. Santa Claus is magical. The laws of physics need not apply. (But if you insist on “scientific” sounding explanations, then fine. Just say he’s got a TARDIS, OK? They don’t all look like police boxes, you know.)

Storytelling-wise, I’m fine with the magical stuff.** The problems I have with the Santa mythology are the many canonical parts of this story that can’t be made to fit together.

Is Santa an elf or not? And if he is an elf, what’s the deal with him and Mrs. Claus not looking like any of the other elves there in his workshop? Santa is supposed to be Father Christmas, but Father Christmas wasn’t an elf. And Santa is also supposed to be St. Nicholas — who wasn’t an elf either. But if he’s St. Nick then he should be, unlike elves, mortal — which he doesn’t seem to be. (If it weren’t for Santa’s ageless immortality, I would reject the “elf” business as nothing more than the side effect of a hastily chosen easy rhyme by Clement C. Moore.)

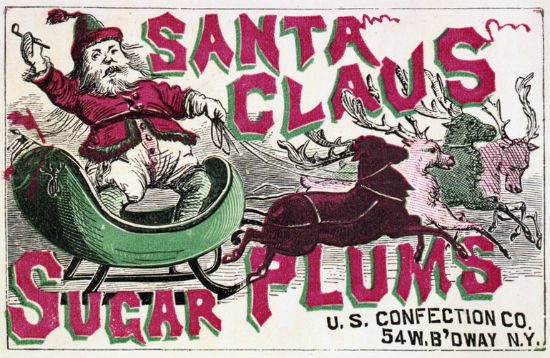

Granted, it shouldn’t be too surprising that our Santa folklore doesn’t quite cohere, because most of it was never really “folklore” to begin with. These stories were shaped and crafted as much by Madison Avenue as by anything else, so the story has had to be constantly readjusted to account for the various things that various marketers were selling.

Miracle on 34th Street is a lovely story, but it’s also an ad for Macy’s — one that includes the address of the store in its title. Still, though, it seems to have become part of the Santa Claus canon.

But what does that even mean? I tend to think of certain Santa stories as being more canonical than others. Here’s a very short list:

• Clement C. Moore’s 1823 poem, “A Visit From St. Nicholas“

• Miracle on 34th Street

• The song “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town”

• The song “Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer,” and probably maybe the Rankin/Bass TV special based on it

All of those are enduring popular variations of this story, but they may vary a bit too much to allow for any coherent idea of a “canonical” Santa Claus. I tend to rank those higher on the scale of canon than other variations, but I’d have a hard time arguing why. Why should “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” be more authoritatively canonical than, say, “Here Comes Santa Claus”? I’m not sure, but I think it is — just as I think the Tim Allen Santa Clause movies are, while amusing, heterodox and non-canonical.

This suggests two projects. First, can we agree on a basic core set of canonical Santa stories that can serve as a standard by which to judge newer or lesser works? And, second, how can we reconcile the contradictions and variations within that set of canonical stories?

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Dungeons & Dragons players long ago realized that Santa Claus seems to have a bag of holding — my favorite magic object in role-playing games just because of its wonderful logistical convenience (even when the DM is a stickler regarding the size of the opening in the bag). If people want to write more of those whimsical science-of-Santa articles, I’d suggest starting with Santa’s bag of holding, an artifact that invites a closer examination of the science of magic. Is the magic of such a bag a kind of stable wormhole between dimensions? Etc.

** Well, mostly fine with it. Santa’s magic is strange in that it seems, at the same time, both limitless and strictly circumscribed. In that sense, he’s a lot like Tom Bombadil. If you think about it for a bit, you may even start to wonder if Santa Claus is Tom Bombadil. And thus also, of course, the other way around.

The next time you’re reading the pre-Rivendell parts of The Fellowship of the Ring, try that out and see if it doesn’t make some weird kind of sense.