“Again I saw that under the sun the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to the skillful; but time and chance happen to them all.”

That’s Ecclesiastes 9:11. It’s Bible. It’s canon, scripture, holy writ, the “Word of God.”

What does the Bible teach about wealth and poverty? That fortune and misfortune are often just a matter of dumb luck. Merit, blessing, cursing, reward and punishment don’t enter into it, “but time and chance happen to them all.”

Given that I’m not an illiterate clobber-texter, I’ll note that this is not The Biblical Teaching about wealth and poverty, but that it is merely a biblical teaching on the subject — one of many such conflicting points of view that don’t easily sit together. We could turn to other passages from that library of holy books and find some that suggest wealth is meritocratic — a reward for virtue or faithfulness or diligence.

And we can turn to even more such passages that suggest wealth is the product and the evidence of sin — of cruelty, oppression, injustice and criminality. The paraphrase of Balzac — “At the root of every great fortune is a great crime” — is also a paraphrase of Isaiah and Amos and James. It is the story of Joseph — the man who stole the world — in the book of Genesis, the book of origins, which ends by explaining the origin of wealth and tyranny.

And we can turn to Jesus, who kicked the whole thing up a notch by posing it as a binary ultimatum: “You cannot serve God and Money.” Period.

Which brings us to this recent piece from Tom Jacobs at Pacific Standard: “Did the Prosperity Gospel Help Elect Trump?”

The prosperity gospel is a peculiarly American pseudo-theology. By one estimate, 17 percent of Americans believe that wealth and power are gifts from God, bestowed on the worthy. By that logic, worldly success signifies a scarcity of sin.

New research suggests that this equation — which is diametrically opposed to most mainstream Christian teaching — may have helped Donald Trump get elected president. In a series of studies, researchers found that political candidates who were described as having successful lives were judged as more ethical than identical candidates with less-impressive track records.

The findings suggest the Trump campaign’s emphasis on the candidate’s success in business — which has subsequently been shown to be based largely on smoke and mirrors — increased the perception that he was a highly moral man, which in turn increased their likelihood to vote for him.

The studies Jacobs cites there correspond with findings from the Pew Research Center, “Partisans are divided over the fairness of the U.S. economy – and why people are rich or poor.”

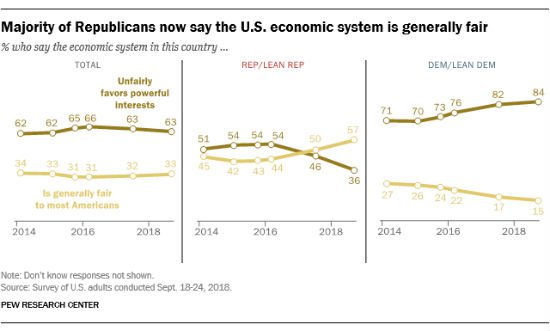

Around six-in-ten U.S. adults (63 percent) say the nation’s economic system unfairly favors powerful interests, compared with a third (33 percent) who say it is generally fair to most Americans, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. While overall views on this question are little changed in recent years, the partisan divide has grown.

For the first time since the Center first asked the question in 2014, a clear majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (57 percent) now say the economic system is generally fair to most Americans. As recently as the spring of 2016, a 54-percent majority of Republicans took the view that the economic system unfairly favors powerful interests.

I’m not sure if this increasing partisan belief is due, in part, to receding memory of the Great Recession or if it’s a perverse product of that gigantic global debacle.

It was just a decade ago, after all, that we witnessed vivid, calamitous proof that “the nation’s economic system unfairly favors powerful interests” and that it is not at all “generally fair to most Americans.” But the Great Recession was also a stark reminder that financial insecurity, homelessness, joblessness, and poverty can strike capriciously, regardless of how prepared or responsible or secure one may have thought oneself until then. It was exactly the sort of random, haphazard distribution of suffering that makes the just-world fallacy seem like an attractively reassuring fantasy. When faced with the prospect that this could happen to you, too, no matter what you try to do about it or how well you prepare, it’s comforting to reject that in favor of a simple formula that rules out “time and chance,” convincing ourselves, instead, that the race is always to the swift, the battle always to the strong, bread to the wise, riches to the intelligent, favor to the skillful, and prosperity to the virtuous.

The victim-blaming aspect of this assertion that life, contra Qoheleth, is “generally fair” isn’t due to a particular animus toward those victims. It’s defensive. “Iniquity is in your hand,” Zophar says to Job, not because he really thinks Job is wicked or guilty or deserving of his misery, but because Zophar is terrified that the same thing might happen to him, just as inexplicably, and he is desperate for some assurance that he is safe from that.

“Who that was innocent ever perished?” another of Job’s friends asked, rhetorically. Eliphaz wasn’t so dumb he didn’t know the answer, he was just scared. He didn’t want to “perish,” so he was clinging to the hope that some kind of innocence might protect him from that fate. He didn’t have anything against Job, personally — and he surely didn’t know anything against Job because there was nothing to know. But what he saw happening to his undeserving friend frightened him so much that he clung ever-tighter to the idea of some meritocratic orderliness of deserving and undeserving, of rewards and punishments.

I suspect that same fear is a big factor in the increasingly partisan desire to pretend that life is “generally fair,” and that the powerful aren’t using their power for their own advantage, and that there’s no need to try to create safety nets or social insurance of any kind to protect one another from “time and chance,” because each of us receives only and all that we have earned.

That’s why I think that one of the best ways of making the case for such safety nets and protections is simply to go about building them and strengthening them whenever and wherever possible. The existence of such protections can reduce the fear that leads all the Zophars and Bildads and Eliphazes to pretend so desperately that such protections aren’t needed.