If you get pulled over here in Pennsylvania, the officer will ask to see your driver’s license, your registration, and your proof of insurance. That’s one thing from your wallet and two other things from somewhere in your glove compartment. The registration is a piece of paper you now have to print out for yourself, and the insurance card is something you get in the mail every six months from your insurer.

This is, basically, homework. And it shouldn’t be necessary, because PA driver’s licenses are scannable. The registration and insurance info could all be maintained right there in the same database as your license info. One card, no pile of papers in the glove compartment that has to be scrupulously overseen every few months.

I suppose some people don’t like that idea because of privacy concerns, but this is all information that at any point you might be compelled to produce on a moment’s notice for a guy with a gun who has forced you to pull over your car. And that guy has the legal authority to confiscate several days’ worth of your paycheck if you can’t produce hard copies of proof that all the paperwork you’ve already paid for is up to date. So I’m not sure “privacy” is quite the right framework here.

There are privacy concerns about these records — your auto insurance company is already trying to collect and monetize as much data about you as they can (including asking to put a GPS tracker on your car). But this is about your own access to your own data, not their access to it. And it’s about your ability to quickly and conveniently provide that information when requested so as not to displease the nice officer with the gun by spending five minutes rummaging through whatever you’ve got in your glove compartment.

So why don’t we do this? Partly because state governments are slow and inefficient. And partly because of Nicolae Carpathia.

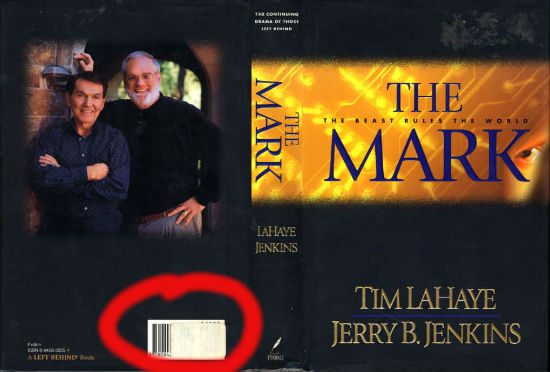

Yes, really, we’re still fumbling with hard-copy print outs and piles of paperwork in part because a significant percentage of our fellow citizens are obsessively worried about the fictional “Antichrist” of Rapture Christianity folklore. And they fear that keeping insurance information where it’s needed right there on your driver’s license is part of a slippery slope leading to the Mark of the Beast, One World Government, and the End of the World. (These folks all say they can’t wait for the End of the World, and they’re otherwise eagerly excited about the prospect of the rise of the Antichrist, but logical consistency has never been their strongpoint.)

The same thing happened back in the ’70s when supermarkets started installing barcode scanners. That’s not something I read about in a history book, it’s something I remember living through at a church and a private Christian school that both scheduled “Prophecy Conferences” as highlights of their annual calendar. When all the adults around you are telling you that the world is going to end before you get to be their age, you tend to remember it.

Eventually, Rapture Christians accommodated themselves to UPC codes. Mostly.

But now they have a host of new technologies to worry about.

It was fascinating for me to read Jordan Frith’s take on this, because he’s coming at this from the opposite side. Frith wrote a book on RFID chips for MIT Press and he recently contributed a column on the subject for The Conversation: “What your pet’s microchip has to do with the Mark of the Beast.”

An almost invisible electronic device used all over the world – best known to much of the public for helping reunite lost pets and their owners, but also found in subway cards, electronic tolling, luggage tags, passports and warehouse inventory systems – has alarmed some evangelical Christian communities, who see in this technology the work of the Antichrist.

In a section of A Billion Little Pieces, my recent book about Radio Frequency Identification chips, also known as RFID chips, I investigate why these tiny items have, in some religious circles, become closely linked with the apocalypse depicted in the biblical Book of Revelation.

My exploration of “Bible-prophecy” arcana led me to also learn about new technologies like RFID chips. Frith’s study of those new technologies forced him to also learn about “Bible-prophecy” arcana.

And Frith seems to have done his homework. His piece is one of the rare mainstream reports that doesn’t parrot back the question-begging argument of premillennial dispensationalist fantasists that they are merely providing a “literal interpretation” of events supposedly “prophesied” in Revelation. He quotes Revelation 13, but then cautiously says this: “This passage is the origin of beliefs around what would eventually become known as the ‘Mark of the Beast,’ a way to identify those who worship the Antichrist.”

That strikes me as a helpful acknowledgement that “Bible-prophecy” scholars’ conclusions involve passages like this, but that their conclusions do not necessarily flow from such passages. Nor are such passages the only — or the main — ingredient in “Mark of the Beast” folklore.

Frith’s kicker shows he has a pretty good grasp on just what that folklore means to those Christians:

There’s something poetic about linking a tiny technology used to identify rescue dogs in a shelter to the Mark of the Beast. After all, there’s likely no more consequential type of identification than the differentiation of the damned from the redeemed.

His column also notes the way that these sectarian fears sometimes lead Rapture Christians into odd alliance with privacy advocates whose protests arise from a very different set of concerns. There may be something promising to that. (Maybe if we start saying “Nicolae Carpathia” instead of “late-stage capitalism” we’ll find some unlikely support from those folks.)

Anyway, none of this changes the fact that I’m still going to have to call my State Farm agent to get him to send me another proof-of-insurance card since the most recent one in the stack in my glove compartment only covers July-December of 2018.