Erik Loomis visited the American grave of Wernher von Braun, thereby sending me down a Google hole.

Here’s the bit that prompted the searching:

After Sputnik, von Braun became a lot more important to the military. Now it was all about space. He might not have his slave laborers anymore, but he was once again catered to, getting most of what he demanded. He moved over to NASA in 1960 and stayed for the next decade. He was very cautious in his experiments, more so than the Soviets, and was blamed by the American military for delays that got a Soviet manned flight into space before the Americans. But von Braun was the lead developer for the famed Saturn rocket, which is what took Apollo 11 to the moon in 1969. He was the most important person behind the creation and development of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville. Throughout this whole period, he embraced one great form of American hypocrisy — he converted to evangelical Christianity while also sleeping with every woman he could find, including many of the women who worked for him.

Wernher von Braun “converted to evangelical Christianity”? How is it that I never heard about this before?

You have to understand that evangelicals love to celebrate famous people who are part of our gang. As a rule, we do not miss the chance to brag about any remotely prominent person whose born-again status allows us to piggy-back on their prominence and cultural influence. It’s almost unheard of for any noteworthy person who might plausibly be claimed as one of us to go unclaimed as such.

It’s kind of like the way my late great friend Dwight Ozard used to interject “Canadian!” before I could even finish any sentence mentioning someone from his home country.

“I just watched all three Back to the–”

“He’s Canadian!”

“Jane, you ignorant–”

“He’s Canadian!”

“I can’t believe a billion people watch Bayw–”

“She’s Canadian!”

The evangelical instinct to claim its celebrities is even more ferocious than that. I grew up about 30 miles from the Meadowlands, but most people at my white evangelical church and private Christian school weren’t Giants or Jets fans. They were Cowboys fans, because Roger Staubach and Tom Landry were evangelicals. (Somewhere I still have a copy of the Spire Christian comic book “Tom Landry and the Dallas Cowboys.”) We’d watch games all but chanting “One of us, one of us” like the extras in Freaks.

So it’s kind of remarkable that I don’t ever remember hearing someone as famous and historically significant as Wernher von Braun celebrated or praised as gabba gabba one of us.

I like to think that this was a matter of discretion — that despite von Braun’s vital role in the space program, his Time magazine covers, and his popular Disney specials — evangelicals still chose not to celebrate his conversion or to trumpet his membership in our tribe because he was also, you know, a big honkin’ Nazi.

Former Nazi, as NASA and Disney always hastened to point out. Former reluctant Nazi, they said, pointing to the very little and very doubtful evidence that his participation in the Nazi war machine was reluctant. (“OK, yes, there’s that one picture of him in his SS uniform, next to Himmler, but only that one picture” is an actual argument made with the intent of defending von Braun.)

Maybe even a religious subculture desperate for vicarious fame and respectability was hesitant to hitch its wagon to the man who designed the V-2 rocket for Hitler, thereby facilitating the murder of thousands of Allied civilians as well as the deaths of some 12,000 concentration camp prisoners forced to work as enslaved labor on the project. Maybe the purported conversion of the real-life inspiration for Dr. Strangelove should be viewed with a bit more cautious skepticism. This was, after all, a man whose entire life story was marked by an eagerness to radically shift his allegiance whenever expedient.

So even though we evangelicals love nothing more than a personal testimony with a redemption arc from the depths of sin, maybe it seemed a bit too much when those depths of sin involved years of being an SS officer using slave labor to build “vengeance weapons” for Hitler.

Except that’s not how this works. As a rule, the more depraved the sinner, the greater the triumph of that person’s conversion and redemption. “Repentant former SS officer begins a new life in Christ” would have made for a very compelling testimony and witness. The model for this kind of story, after all, is John Newton — the captain of a slave ship before the “Amazing Grace” of his repentance and conversion.* So Wernher von Braun’s conversion testimony should have been not just welcome, but immensely popular.

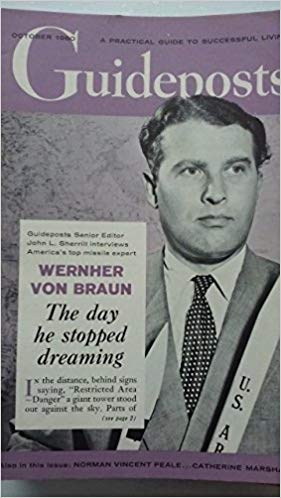

For a while, I think it was. Back at the beginning of the space race, when von Braun was at the height of his fame as an all-American rocket man, he was featured in a cover story for Guideposts magazine.** (This was in 1960, before white evangelicals came to view Guideposts as too squishy to count as truly evangelical.) I doubt von Braun is the only former Nazi to ever have his story of faith and inspiration featured on the cover of that magazine, but he’s probably the least remorseful former Nazi to be featured there.

For a while, I think it was. Back at the beginning of the space race, when von Braun was at the height of his fame as an all-American rocket man, he was featured in a cover story for Guideposts magazine.** (This was in 1960, before white evangelicals came to view Guideposts as too squishy to count as truly evangelical.) I doubt von Braun is the only former Nazi to ever have his story of faith and inspiration featured on the cover of that magazine, but he’s probably the least remorseful former Nazi to be featured there.

And that’s what makes Wernher von Braun’s “personal testimony” so tepid and unconvincing. There’s no element of repentance or remorse. Whatever von Braun meant by his conversion, it didn’t involve “I once was lost but now am found / was blind but now I see.” He always insisted, instead, that he was never genuinely lost, or truly blind — that he was somehow never really a Nazi — but that he was just playing along because he had no choice or because he only ever cared about building his rockets.

One gets the sense, rather, that von Braun eventually became a Christian for the same reason and in the same way that he became an American. “My country has lost two world wars,” he said, “This time I want to be on the winning side.”

So maybe the reason I never heard about the famous Christian Wernher von Braun was that most evangelicals weren’t entirely convinced by his conversion story. Maybe that’s why I never wound up with a Spire Christian comic with his name on the cover.

But thanks to going down that Google hole, I’ve learned that von Braun is enjoying a 21st-century revival among one strain of American white evangelicalism: Creationists love the guy.

Answers in Genesis includes a glowing profile of von Braun for its “Profiles of Creation Scientists” series. It rehashes all of the revisionist dismissals Operation Paperclip originally pushed to cover for the amnesty granted to von Braun and other Nazi scientists deemed to be useful to America’s Cold War interests. AiG’s celebration of von Braun’s Christian faith is as gushing as it is fraudulent:

He had full confidence in the truth of the Bible, describing it as ‘the revelation of God’s nature and love’. He acknowledged his dependence on God in prayer, not only in times of crisis such as during his escape from Nazi Germany, but also in his work—such as praying for the safety of the manned space flights.

Here’s another creationist site that offers a gushing, “inspirational” retelling of von Braun’s conversion. David Coppedge’s long hagiography of the former SS officer appends a few pop-essays written by von Braun himself, extolling a kind of generic, civil religious faith.

Coppedge also appends the text of a 1972 letter von Braun wrote to the California State Board of Education arguing for teaching something like intelligent-design creationism in public schools. That letter is the primary reason von Braun is such a hero to creationists today.***

The letter from von Braun doesn’t really read like the kind of culture-warrior creationist nonsense promoted by outfits like Answers in Genesis. It reads more like the kind of porridge produced by contemporary writers shooting for some of the sweet Templeton money that funds so many similarly gooey essays on “Science and Religion” nowadays.

It reads less like something written by a convert to evangelical Christianity than it does like something written by a pragmatic nominal Lutheran whose main concern regarding his Nazi past is how it will affect his reputation and respectability.

Overall, then, I’m not wholly convinced that von Braun really converted to evangelical Christianity as much as that he was a thoroughly unprincipled pragmatist who found himself living in Texas and Alabama. Kind of the same way I feel about Robert Jeffress.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

* This folklore about Newton’s conversion and his writing of “Amazing Grace” is not true. And it’s not true in a rather important way.

Newton wasn’t the captain of a slave ship when he experienced his born-again conversion to evangelical Christianity. He was, at that time, only the first mate on a slave ship. He only became a captain years later, spending nearly another decade as both a slaver — a kidnapper, torturer, trafficker, thief and murderer — and an evangelical Christian.

Then he got married, left the sea, worked as a customs agent, eventually became an Anglican clergyman, later wrote “Amazing Grace, and then, many years later, became an outspoken abolitionist.

A timeline:

1748: Newton begins his career in the slave trade, has a conversion experience during a fierce storm at sea.

1748-1754: Devout Christian Newton works in the slave trade, advancing to become captain of his own slave ship.

1754: Devout Christian Newton gives up sailing for work as a customs officer/tax collector, continues investing in the slave trade.

1764: Newton is ordained an Anglican priest.

1772: Newton writes the words to “Amazing Grace.”

1788: At the age of 63 — 40 years after he became a born-again Christian and 16 years after writing his most famous hymn — Newton becomes an abolitionist.

The actual history of Newton’s four-decade long conversion is far more interesting, instructive, and inspirational than the folklore of his supposed instantaneous conversion during a storm at sea.

** If some enterprising American religious studies professor decided to research and analyze everyone who has ever appeared on the cover of Guideposts and what this tells us about American Christianity and civil religion, then I, for one, would be very eager to read that paper.

*** For Coppedge specifically, this affection is also personal — Coppedge worked on the Cassini project for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and has since made his living promoting himself as someone unjustly fired for his Christian faith. He views Wernher von Braun as a kindred spirit — as a rocket engineer who regards faith and science as inextricably linked and who believes that legitimate science requires “belief in the certainty of a Creator.”

I think his search for a kindred spirit would be better directed to Jack Parsons — a rocketry pioneer and prodigy who helped to found the JPL before losing both his fortune and his girlfriend to L. Ron Hubbard, and then losing both the map and his marbles.

P.S. The title of this post comes from a Mort Sahl joke about the fawning Hollywood biopic — a box office flop — that von Braun himself pushed for. The movie was called I Aim at the Stars, and Sahl suggested “But Sometimes I Hit London” as a subtitle.

Wernher von Braun was a very strange man. Among other things, he wrote a book called Project Mars: A Technical Tale, which was part science fiction novel and part engineering schematic for an actual Mars mission. In the imagined distant future of 1980 in von Braun’s story, a grim peace reigns enforced by a nuclear-armed Death Star — a 440-crew-member space station he called “Lunetta.”

Learned that from Michael Mark Cohen’s long, fascinating discussion of von Braun’s life: “The Whitest Man Who Ever Lived.” Cohen mentions, but doesn’t spend a lot of time on, von Braun’s “evangelical Christian” conversion. That’s probably appropriate.

Anyway, here’s the Tom Lehrer video you’ve been patiently waiting for: