Originally posted June 22, 2010.

You can read this entire series, for free, via the convenient Left Behind Index. The ebook collection The Anti-Christ Handbook: Volume 1, is sporadically available on Amazon for just $0.99. Domestic political errand. Volume 2 of The Anti-Christ Handbook, completing all the posts on the first Left Behind book, is also now available. Volume 3 is coming someday.

Tribulation Force, pp. 236-243

The Tribulation Force gathers in Bruce’s office for their meeting.

Bruce announces that he wants everyone “to put on the table everything that was happening in each life.” He goes first, repeating his usual maudlin refrain about “his own sense of inadequacy” and shame, guilt, etc.

He also admitted his loneliness and fatigue. “Especially,” he said, “as I think about this pull toward traveling and trying to unite the little pockets of what the Bible calls ‘tribulation saints.’”

Here’s the thing about “what the Bible calls ‘tribulation saints’”: The Bible never calls them that. You won’t find that phrase in the Bible, or any close-sounding term referring to any such group of people. You won’t find any reference to any such group at all. The term and the idea are part of Tim LaHaye’s End Times framework, but they can’t be found in the Bible.

The closest you could come to such a thing, and the passage Bruce/LaHaye would cite to defend the claim that “the Bible” says anything about it, is this, from Revelation 13:7:

[The Beast] was given power to make war against the saints and to conquer them. And he was given authority over every tribe, people language and nation.

That, Bruce/LaHaye says, tells us of the tribulation saints suffering under the Antichrist. Even if it never mentions either one. John of Patmos was writing, explicitly, “To the seven churches in the province of Asia.” Interpreting that “literally,” LaHaye believes John’s book was actually addressed to the post-church “tribulation saints,” 2,000 years in the future, far away from the province of Asia Minor. This again is the sort of thing Tim LaHaye always means when he says he’s interpreting the Bible “literally.” John, writing to actual Christians in an actual place during an actual time of actual persecution, wasn’t actually addressing any of those things. Not those Christians in that time and place, and not that persecution.

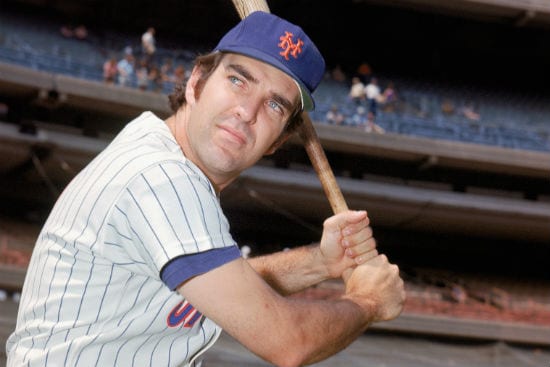

Once you adopt the habit of this kind of “literal interpretation,” it’s not much of a leap to say that the Bible speaks of “tribulation saints,” or of “The Antichrist” or “the Rapture” or of “longtime New York Mets first baseman Ed Kranepool.” None of those things are ever mentioned, directly or indirectly, in the Bible, but they are all routinely described by Bruce and the authors as being spoken of directly by that text. (Except, of course, for Ed Kranepool — who, unlike those other things, really exists.)

Buck half-listens to Bruce, but what he’s really thinking the whole time is that he “wanted to come right out and ask why he hadn’t simply signed a card on Chloe’s flowers.” You know, the really important stuff.

I’m going to give Jerry Jenkins credit here for another piece of apt, if unintended, realism. This is exactly how most small-group Bible studies work. The leader asks everyone to go around the circle and share what is “happening in each life,” and the members mostly, like Buck, only half listen, concentrating instead on what they’re going to say when it’s their turn, or on what they’d like each speaker to be discussing instead of whatever it is they’re actually prattling on about. It ain’t pretty, but it rings true.

Bruce finally captures Buck’s full attention by discussing something Buck is interested in: Buck.

“This may shock all of you, because I have not expressed an opinion yet, but Buck and Rayford, I think both of

you should seriously consider accepting these jobs.”

That threw the meeting into an uproar. …

Buck agrees that Rayford ought to take his offer, and Rayford agrees that Buck ought to take his, but both continue — as they have for the past 200 pages — to insist that their lofty principles forbid them from working for the Antichrist, even as a double-agent.

“What’s the advantage?” Rayford said.

“Maybe little to you personally,” Buck said, “except for the income. But don’t you think it would be of great benefit to us to have that kind of access to the president?”

He has a point. I can’t imagine, for example, that any agent of the French Resistance would have turned down the chance to serve as Marshal Petain’s chauffeur.

What’s bizarre here, though, is that everyone seems to regard “income” as a factor worthy of consideration. There wouldn’t be a whole lot of advantages to being what the Bible never calls “tribulation saints,” but one such advantage, if there were such a thing, would be no longer needing to worry much about income or saving for retirement. I’m guessing that whatever Rayford has in the bank would be more than enough to last the next seven years. Supplement that with an aggressive reverse mortgage and he and Chloe could live comfortably until kingdom come while devoting their full attention to the agenda of the Tribulation Force.

But then the Tribulation Force doesn’t really have an agenda other than the vague outlines of Bruce’s Big Hole Master Plan (Step 1: dig a big hole; Step 2: hide in it). And none of its members have yet begun to grasp the finality of their final seven-year countdown. So they’re still oddly considering things like income and benefits when discussing Rayford and Buck’s job prospects.

“Sir,” Buck said, “the very fact that you’re not angling for it is a good sign. If you wanted it, knowing what you know now, we would all be worried about you.”

Rayford’s reluctance, the authors assert for the hundredth time, is a sign of his humility. And that can be true. It can also be true, however, that a showy pose of reluctance is a sign of false humility. We discussed last week how the extravagant reluctance of Rayford and Buck has functioned in this book to allow Jenkins to introduce an array of characters who come forward to try to persuade them, and how each of these characters seems to exist mainly to assert how very extra specially special our heroes are. But there’s also a real-world counterpart here to the protagonists’ getting dragged against their will into these positions of prestige and power. Their reluctance comes straight out of Beverly LaHaye’s personal testimony.

Tim LaHaye’s wife is an influential lobbyist and the chief executive of a massive organization. Concerned Women for America advocates “traditional” gender roles. They attribute many of the ills afflicting America to the evils of feminism, which has lured many women to abandon their divinely ordained role by pursuing careers and “work outside the home.” But Beverly LaHaye herself works outside the home. She runs the company, and she does that from an office 3,000 miles from her husband’s home.

And all of that would be terribly wrong of her if she had wanted any of it, if she had chosen it for herself or even enjoyed the thought of such ambitions. But Beverly LaHaye insists it was all God’s will, not her own. God dragged her kicking and screaming into the executive suite and into the halls of power. So that makes it OK.

More than just OK, actually. Conveniently, it also makes it beyond criticism or question.

I think there’s a bit of that going on here in the long saga of Rayford and Buck refusing to accept these jobs offers. Mostly, though, I think it’s just over-the-top false humility.

So Buck tries to convince Rayford to take his job while Rayford refuses, trying to convince Buck to take his:

“Maybe I should take your job and you should take mine,” Buck said, and finally they were able to laugh.

You can see where this is headed, but then you could see where this was headed 200 pages ago when both characters first began insisting that they would never, ever accept these jobs.

Chloe broke the logjam. “I think you should both take the jobs. … One or both of you should get as close to [Nicolae] as possible.”

Buck counters with a three-point argument: 1) I’m scared of Nicolae; 2) Nicolae is scary; and 3) I have journalistic principles that in this case conveniently allow me to avoid doing scary things. Chloe deals with each of these objections in turn.

“I was close to him once,” Buck said. “And that’s more than enough.”

“If all you care about is your own sanity and safety,” Chloe pressed. … “But without someone on the inside, Carpathia is going to deceive everyone.”

“But as soon as I tell what’s really happening,” Buck said, “he’ll eliminate me.”

“Maybe. But maybe God will protect you too. Maybe all you’ll be able to do is tell us what’s happening so we can tell the believers.”

“I’d have to sell out every journalistic principle I have.”

“And those are more sacred than your responsibilities to your brothers and sisters in Christ?”

I think Chloe gives Buck too much credit on that last point. If his objection were really driven by his concern for “journalistic principle,” then he’d have brought that up first.

Once Chloe takes charge the argument is over pretty quickly. No one really has any response or rebuttal, even though she’s advocating a major departure from Bruce’s Big Hole Master Plan.

Bruce suggested they pray on their knees — something each had done privately, but not as a group. Bruce brought his chair to the other side of the desk, and the four of them turned and knelt.

What follows is two pages of something a better or a wiser writer wouldn’t even have attempted. We’ve discussed several times previously the problem of attempting to portray spiritual intimacy and spiritual ecstasy. It is, like sexual intimacy and sexual ecstasy, a real thing and a good thing and a sacred thing. But it is also, like sexual intimacy and sexual ecstasy, an intensely private thing — a thing that it is almost impossible to portray without being pornographic or laughable or both at once.

The group kneels to pray and I think, “Oh, no. Fade to black, for the love of all that’s holy — fade to black!”

But Jenkins doesn’t. He’s determined to walk us through this. The result is not quite the voyeuristic embarrassment I dreaded. Instead of feeling like an unseemly intruder on another’s intimate moment, I find myself merely unconvinced. I believe that Rayford passionately and sincerely wants to be passionate and sincere, but I can’t quite believe he is. Jenkins’ description of this prayer session is at once overly eager to please and oddly detached, like a transcription of glossolalia.

Here’s the best of it:

The overwhelming sense of unworthiness seemed to crush him, and he slipped to the floor and lay prostrate on the carpet. A fleeting thought of how ridiculous he must look assailed him, but he quickly pushed it aside. No one was watching, no one cared. And anyone who thought the sophisticated airplane pilot had taken leave of his senses would have been right.

Rayford stretched his long frame flat on the floor, the backs of his hands on the gritty carpet, his face buried in his palms. Occasionally one of the others would pray aloud briefly, and Rayford realized that all of them were now facedown on the floor.

Rayford lost track of time, knowing only vaguely that minutes passed with no one saying anything. He had never felt so vividly the presence of God.

The bit with the gritty carpet isn’t bad, but mainly methinks the man doth testify too much. I can’t believe the lavish assertions of “unworthiness” from a man who reflexively describes himself to himself as “the sophisticated airline pilot.” The reader doesn’t get a sense of Rayford communing with the vivid presence of God, but of Rayford communing vividly with Rayford’s sense of Rayford’s devotion. God doesn’t need to be present for that sort of religious experience. I’m not sure that sort of religious experience even allows room for God.

He was not sure how long he lay there, praying, listening. After a while he heard Bruce get up and take his seat, humming a hymn. Soon they all sang quietly and returned to their chairs. All were teary-eyed. Finally Bruce spoke.

“We have experienced something unusual,” he said.

And in the hushed and holy afterglow of this mysterious, sacred encounter with the numinous, they realize that it is at last time to confront the matter of Bruce and the Flowers.

I’m not kidding. Jenkins segues directly from prostrate weeping to who sent the flowers?

“If there is anything between any of us that needs to be confessed or forgiven,” Bruce continues as they all sit there, teary-eyed, “let’s not leave here without doing that.”

“There is something I would like clarified,” Chloe responds. “I received some flowers anonymously …”

And just that suddenly you go from feeling like you’re watching worship porn to feeling like you’re watching a worship-porno blooper and gag reel.

For the record, Bruce didn’t send the flowers after all. Once he clears that up, they resume the usual business of a Trib Force meeting as though they hadn’t “experienced something unusual” and nobody says anything more about the flowers and/or the spiritual ecstasy until they’re getting ready to leave.

Buck turned to Rayford. “As wonderful as that prayer time was, I didn’t get any direct leading about what to do.”

“Me either.”

“You must be the only two.” Bruce glanced at Chloe and she nodded. “It’s pretty clear to us what you should do.”

Notice that it’s the two non-POV characters who “got” the “direct leading.” That handily allows the authors to avoid having to describe what such explicit divine guidance looks like. Or, more accurately, what it feels like, because such “direct leading” isn’t usually regarded as something seen or heard as much as something felt. And having to describe what such feelings feel like or how they might be deemed meaningful apart from any recourse to reason or experience or evidence — any of which would diminish the directness of this direct leading — might jeopardize the whole racket. To describe such things would be to risk exposing claims of such “direct leading” to the sort of evaluation that would undermine their function as trump-cards of unquestionable authority.

Let me be clear. I’m not saying that the sort of “direct leading” explicitly cited but only vaguely described here is impossible. Maybe God is trying to tell you something. But it could just as possibly be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato.

If someone claims to have received “direct leading” from God, then I don’t regard the depth of their passion or sincerity as having any bearing on the validity of their claim. Nor am I particularly concerned with whether they’re hearing voices, seeing visions, dreaming dreams or just getting some kind of feeling in their gut. What I’m most interested in is the substance of this alleged leading. You say God is leading you to go back to school to become a teacher? Well, maybe that’s so. You say God is leading you to pursue a music ministry? Well, I’ve heard you sing, and you might want to double-check that one. You say God wants you to sacrifice your first-born son? Now I’m sure you’re wrong, but stay right here and tell me more about it while I just quickly dial these three numbers …

The prophet Micah says, “What does the Lord require of you? To do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with your God.” That right there is some pretty direct leading.

If you tell me that you’ve received a “direct” message from God to do justice, love mercy and walk humbly, I’m inclined to believe you. If you tell me that God has given you some kind of “direct leading” away from justice, love, mercy and humility, then I say “Bah, humbug.”

Neither Buck nor Rayford seems interested in hearing more about the explicit supernatural instruction that Bruce claims to have just received about their respective futures. That seems odd. “God has just spoken to Chloe and I about your future,” Bruce tells them. “OK, then, good night,” they say.

Shouldn’t they at least be a little bit curious? I mean, if somebody said, “Hey, I was just talking to George Clooney the other day and he said something about you,” wouldn’t you want to know what it was he said? And if that’s true for George Clooney, shouldn’t it also be somewhat more true for, you know, God?

But Buck and Rayford just leave without discussing this direct leading any further. Buck walks Chloe to her car, but even though his girlfriend has just indicated that she has received a personal transmission from the Lord of Hosts about the specifics of his future, he doesn’t ask her anything about what God had to say. Instead, he just teases her about having a “secret admirer.”

“Seriously,” he says, “who do you think it is?”

Anonymous flowers are apparently a far more powerful tool of sabotage than I would have thought. One well-timed bouquet has derailed and disrupted the entire Tribulation Force for more than 240 pages so far.

I wonder if this works in real life. Picture this: Concerned Women for America is about to launch its next big legislative campaign against equal rights for LGBT people when a delivery man arrives with a giant bouquet of flowers for Beverly LaHaye. The unsigned and untraceable card says only “Always.” It might not work, but it could be worth a try.