John Oliver’s team did a terrific job on Last Week Tonight covering as much of the subject of police reform as they could in half an hour. It’s informative, entertaining, funny, and yet righteously angry. Watch the whole thing:

At about the 10 minute mark there, Oliver & Co. replay a 2016 clip from former Dallas Police Chief David Brown lamenting that “we’re asking cops to do too much in this country.” We discussed that clip here back in 2016 during a previous iteration of the cycle of protest and failed reform.

Brown’s words remain important, I think, because they highlight the flipside of the problem, which is also a big part of its cause. Here again I’ll risk losing your attention by discussing this in the framework of “subsidiarity” — the principle from Christian political thinking (but not exclusively from Christian thinking) that helps us to think more clearly, and to act more justly, by emphasizing and clarifying that moral responsibility is always both universal and differentiated. This is what the Bible talks about in that section of the epistles that talks about an “inescapable network of mutuality.”

I sometimes describe subsidiarity by asking “Who is ‘you’?” If you are a sibling, you’re responsible for being a good sibling, but that gets harder to do if your other siblings are irresponsible, or if your parents are irresponsible. It’s more difficult to be a good sibling with irresponsible, crappy parents because in addition to the proper role you need to play as a sibling, you’re also forced to pick up the slack for your parents, fulfilling the responsibilities they’ve left unattended. That’s extra work. It’s not supposed to be your job and you’d be much better able to do your job if you didn’t also have to do their job.

That’s what Chief Brown was expressing as his frustration that “we’re asking cops to do too much.” He’s right — for specific values of “we” in that sentence. “We” — the city and county, state and federal governments and the budgets they produce — have been asking the police to take on responsibilities that shouldn’t be their job, responsibilities that we should not and cannot expect them to be any good at fulfilling.

But as we’ve seen, and as we’ve shown this past week, there’s also another “we” made up of millions of ordinary members of our community that is asking the police to do a lot less in this country. This “we” is asking the police to stop taking on responsibilities and tasks that lie beyond the essential functions they are intended to perform. They’re asking that different actors and institutions be asked, or be created, to attend to the responsibilities that ought not to belong to the police.

This request is being received by many police departments as a threat — one they’re determined to crush, violently and lawlessly. That’s immoral and dumb for a host of reasons, but it’s particularly immoral and dumb given that the response from the police themselves ought to be “Yes, please, thank you so much for saying so.”

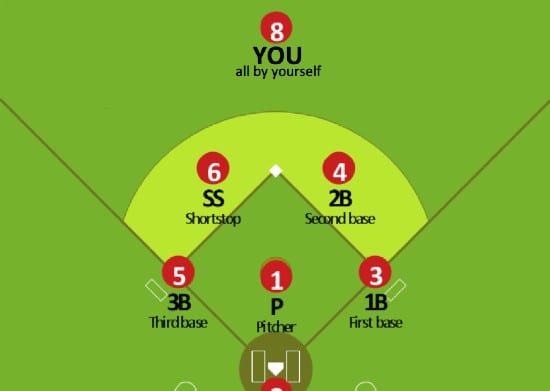

Imagine that you’re the center fielder on a baseball team.

But in order to save money — and to offer popular cuts in ticket prices, including free luxury seats for select fans — the team’s management has decided not to hire anyone to play left field or right field. Instead, they’ll be depending on you, alone, to defend the entire outfield, from foul pole to foul pole, all by yourself.

Initially, this might seem like quite the ego-boost. Management is telling you that you’re so good, so special, that you can do what most teams use three people to do! Maybe they even boost your salary a bit since they don’t have to pay those other outfielders anymore. Awesome!

But this would get tiresome very quickly. Your team is going to lose every game. You’ll be exhausted and demoralized, quickly realizing that you’re not three times better than any other outfielder, just three times less effective.

You’ll realize that no matter how much management tries to spin this as a sign of your immense value, they’re actually overworking you, asking you to do more than they should — to do more than you can. And all those long innings chasing blooper doubles hundreds of feet away will vastly outweigh that little boost in salary they gave you. You might have once been a good center fielder, but without teammates carrying their share of the defense, you will suck at your job.

And no one likes sucking at their job.

So when the fans start booing every inning, protesting how routine fly balls turn into 10-run rallies for the other team, those boos ought to be music to your ears. Give the fans what they want, you’ll think, stop asking me to do too much and just let me cover the one part of the outfield I’m supposed to be responsible for and let me leave the rest to somebody else.

You’d have to be a raging narcissist as well as an idiot to be offended at the suggestion that your team needs a left fielder and a right fielder too — that they need to stop relying on you to do what even Willie Mays or Andruw Jones or any of the DiMaggios couldn’t be expected to do alone. You ought to be grateful for the boos, because what they’re asking for might one day let you go back to doing your job, and only your job, and to possibly again being proud of that work.

If you didn’t see it that way, the fans would start booing you too. And they’d be right to do so. Because that’d be a sure sign that you probably wouldn’t be content with just playing three positions by yourself. You’d be demonstrating the kind of maniacal ambition that won’t be satisfied until you were playing all four infield positions too — and also pitching and, somehow, catching as well. You’d be revealing yourself as someone who didn’t care about losing 162 games and turning the team into an unwatchable laughingstock, because you’d rather suck at nine positions than just play one well.