The Wikipedia page on “The history of the ambulance” is an interesting read. Here’s how it starts:

The history of the ambulance begins in ancient times, with the use of carts to transport patients. Ambulances were first used for emergency transport in 1487 by the Spanish forces during the siege of Málaga by the Catholic monarchs against the Emirate of Granada, and civilian variants were put into operation in the 1830s. Advances in technology throughout the 19th and 20th centuries led to the modern self-powered ambulances.

That doesn’t really get at what we mean today when we talk about an “ambulance.” We’re not just referring to a cart for the transport of the sick or wounded — whether that cart was horse-drawn or engine-driven. What we really think about as an “ambulance” is a not just the vehicle that transports patients to the hospital, but the vehicle that transports medical first responders from the hospital to wherever the patient is. It turns out that’s a very different history than “the history of the ambulance.”

And it’s a much more recent, and much more interesting, history. It’s a history I’d never really thought about before and thus something I’d blurrily projected back onto the past. I’d read about how, say, Ernest Hemingway or e.e. cummings had enlisted as ambulance drivers during World War I and anachronistically embellish that to imagine them as paramedics or EMTs, when really they were just taxi-drivers for the wounded.

So when did that change happen? When did “modern self-powered ambulances” evolve from simple transport vehicles to actual providers of life-saving emergency medical care on-site and en route? That Wikipedia article isn’t much help regarding that part of “the history of the ambulance.” It lapses, instead, into a passive-voice porridge that tells us stuff happened, somehow, without ever mentioning who acted, or how:

After the Harrow and Wealdstone rail crash in 1952, ambulances in Britain were restructured to be a “mobile hospital,” rather than just transporting patients, thus leading to modern ambulances. CPR was developed and accepted as the standard of care for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; defibrillation, based in part on an increased understanding of heart arrhythmias, was introduced, as were new pharmaceuticals to be used in cardiac arrest situations … and well-developed studies demonstrated the need for overhauling ambulance services. These studies placed pressure on governments to improve emergency care in general, including the care provided by ambulance services. Part of the result was the creation of standards in ambulance construction concerning the internal height of the patient care area (to allow for an attendant to continue to care for the patient during transport), and in the equipment (and thus weight) that an ambulance had to carry. … Ambulance design therefore underwent major changes in the 1970s.

The story beneath that passive-voice pudding is revolutionary — and surprisingly timely. “CPR was developed,” yes, but by whom? Well, by a bunch of physicians in the mid-20th century, one of whom was Dr. Peter Safar, an anesthesiologist who helped to codify and formalize the process we now know as “CPR.” If you’ve ever taken CPR training, you’ve followed Safar’s curriculum, probably using one of the “Resusci Anne” mannequins that he invented.

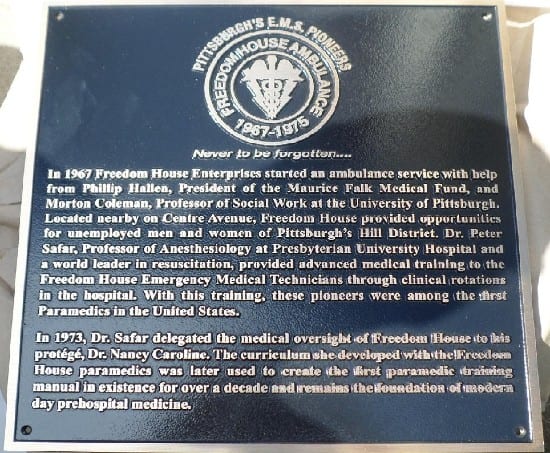

And what of the “well-developed studies” that “demonstrated the need for overhauling ambulance services”? That would probably include the 1966 National Academy of Sciences publication “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society,” which in EMS circles, apparently, is usually just called “the white paper.” This is another thing I had never heard of before, but I learned of it reading this article from last spring in the trade publication EMS World, “The Forgotten Legacy of Freedom House.” I found that, in turn, thanks to this Twitter thread from author Jamie Ford, who uses the story of Freedom House as an illustration of what it means to “defund the police” — and of the enormous benefits that can come from that.

Freedom House, you see, was really the first organization to provide “ambulance” service in the sense we all assume and expect when we talk about that now in 21st-century America. It’s where “ambulance” came to mean something more than just a hospital’s version of an airport shuttle. It was the first service that meant calling an ambulance meant getting emergency medical care from trained EMTs and paramedics, first responders who could save lives by starting medical care before patients even arrived at the hospital.

And it’s a really good story. It happened in Pittsburgh in the late 1960s, and it involves Dr. Safar, the War on Poverty, and anti-police protests usually referred to now as “riots.”

Most of yins, like me, probably don’t know this Pittsburgh story. I missed this short report on it five years ago from Erika Beras of NPR’s Code Switch team, “How Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Pioneered Paramedic Treatment.”

In the 1960s, Pittsburgh, like most cities, was segregated by race. But people of all colors suffered from lack of ambulance care. Police were the ones who responded to medical emergency calls.

“Back in those days, you had to hope and pray you had nothing serious,” recalls filmmaker and Hollywood paramedic Gene Starzenski, who grew up in Pittsburgh. “Because basically, the only thing they did was pick you up and threw you in the back like a sack of potatoes, and they took off for the hospital. They didn’t even sit in the back with you.”

Ambulances existed, but they were privatized and didn’t offer emergency care or go everywhere.

That changed with the start of the Freedom House Ambulance Service, the city’s first mobile emergency medicine program. Starzenski tells the story in his documentary Freedom House Street Saviors.

The service became the national model, but it started out by serving Pittsburgh’s mostly black Hill District.

Here’s the trailer for Starzenski’s 2010 documentary:

Those men you see interviewed, they were the first EMTs, the first paramedics. Not just in Pittsburgh, but anywhere. The first “ambulance” driver may have been some poor Spanish conscript back in the 15th century, but the men who made up the first-ever ambulance squad with trained paramedics? Those guys are still around.

George McCrary was one of them. Beras interviewed him back in 2015, in Pittsburgh, where he now drives a taxi:

Freedom House became so successful that it attracted the city’s attention, and in the mid-1970s, the city took it over. Pittsburgh has since become a healthcare hub.

Some of the EMTs went on to work for Pittsburgh Emergency Medical Services, but George McCrary was not one of them. For the last three decades, he’s been driving a yellow cab. He loves to tell his passengers the little-known story of Freedom House.

“You can’t say you can meet the first doctor,” he says. “And you can’t say you can meet the first police officer. But you can say you met one of the first American, worldwide, EMT paramedics.”

Valerie Amato’s EMS World article tells the story in more detail than Beras’ 4-minute spot is able to provide. It illustrates the kind of transformative good that can come from what someone once called “the audacity of hope.”

Read that whole article. This is how the emergency medical service we now take for granted came to be. It’d make a terrific big-budget Hollywood movie.

It might be a good thing that nobody tried to make that movie just yet because they’d probably have turned it into another boilerplate white-savior story centered around Safar or maybe around Dr. Nancy Caroline, sidelining the black men whose heroic service turned the doctors’ abstract ideals into reality. I think it’d be more compelling, and more truthful, to see this story told through their eyes, accepting the challenge and stepping up to create and embody an entirely new profession and standard.

As Jamie Ford pointed out on Twitter, this story remains urgently timely because it reminds us that Just The Way Things Are does not have to be The Way Things Will Always Be. In 1966, most people in Pittsburgh — like most people everywhere — assumed that calling an “ambulance” meant calling the cops, who would then show up with a glorified hearse, chuck a stretcher in the back, and then hightail it to the hospital. Dr. Safar’s young daughter had died of an asthma attack because that was all that “ambulance” meant back then. Legendary former Pittsburgh mayor (and former Pennsylvania governor) David Lawrence died in 1966 due to this kind of ambulance service.

Safar envisioned something better. But his solution didn’t involve fussing about with minor reforms like new training classes for the police. It involved creating something entirely new. And that something new started in the part of town where nobody worried about getting rid of help from the police because, in that part of town, the police had never been much help in the first place.

In 1966, Freedom House Enterprises was a Pittsburgh nonprofit “that helped black people find jobs, register to vote, and organize NAACP meetings.” They weren’t previously involved in recruiting, training, or operating professional emergency medical services because no such thing yet existed. But then they decided to do it, and then they did, and now it does.

Today, in 2020, calling an ambulance means summoning the kind of professional emergency medical care first demonstrated by the corps of men who formed Pittsburgh’s pioneering Freedom House Ambulance Service. The problem today is that millions of Americans are reluctant to call an ambulance because doing so might mean bankruptcy due to outrageous medical insurance costs. It’s tempting to think that this is Just The Way Things Are and thus that this is The Way Things Will Always Be. But that’s another reason this hidden gem of a story is so timely. It not only proves that change is possible, it demonstrates what it takes to make it happen.