One of the most cursed objects in my house is a paperback I picked up from the $1 table at a used bookstore. I overpaid.

It’s a 1972 collection of “poetry” by 1970’s counter-culture socialite Ira Einhorn, titled 78-187880, and it’s terrible. I only managed to plow through maybe a third of it before giving up. I’d expected Einhorn’s drug-addled rambling to at least have some of the Aquarian charms of Hair, or something that would explain his brief fame as the academic-turned-Hippie guru “Unicorn.” But no. It’s just a rambling, tedious collection of random, shallow, stale observations mixed with angels, aliens, and paranormal paranoia. Einhorn’s “poetry” achieves the rare feat of being both outrageous and dull, yielding no memorable insights or images or turns of phrase. It’s just awful.

This was a relief. I was pleased to realize that Einhorn’s book was utterly and irredeemably worthless because Ira Einhorn was not just a terrible poet, a terrible writer, and a terrible thinker, he was also a terrible human being who did terrible things to other people.

Wikipedia has a useful summary of Einhorn’s crime:

Einhorn had a five-year relationship with Holly Maddux, a graduate of Bryn Mawr College who was originally from Tyler, Texas. In 1977, Maddux broke up with Einhorn and went to New York City, where she became involved with Saul Lapidus. On September 9, 1977, Maddux returned to the Philadelphia apartment she had previously shared with Einhorn to collect her belongings (which Einhorn had reportedly threatened to throw out into the street as trash) and was never seen again. Several weeks later, the Philadelphia police questioned Einhorn about her disappearance. He claimed that Maddux had gone out to the neighborhood co-op to buy some tofu and sprouts, and never returned.

Einhorn’s initial alibi came into question when his neighbors began complaining about a foul smell coming from his apartment, which in turn aroused the suspicion of authorities. Eighteen months later, on March 28, 1979, Maddux’s decomposing corpse was found by police in a trunk stored in Einhorn’s closet. After finding the body, a police officer reportedly said to Einhorn, “It looks like we found Holly,” to which he reportedly replied, “You found what you found.”

A wealthy heiress caught up in Einhorn’s Svengali shtick hired him a high-priced lawyer, Arlen Specter, who convinced a judge that Einhorn wasn’t a flight risk. The Unicorn promptly skipped bail and fled to the south of France where he lived off the wealth of his supporters and successfully fought extradition for 20 years. (Arlen Specter later became my senator, which is why I picked up Einhorn’s book. Alas, Arlen never stuck around long enough after his town hall meetings to give me a chance to ask him to sign it for me.)

Eventually, Einhorn was returned to Pennsylvania where a jury rejected his bonkers conspiracy defense (he claimed he was framed by MK Ultra secret agents because he Knew Too Much) and he was sentenced to life without parole. Einhorn was 79 when he died in a state prison earlier this year.

So you can see why I was pleased and relieved that Einhorn’s book wasn’t any good.

Imagine the position I’d be in if I’d found his poems to be in any way insightful or inspiring or influential. That would have been deeply unsettling, and it would have required a lot of difficult effort and exploration — hours, or even years, of trying to sift through what I had learned, trying to separate the good from the ways it was tainted by or connected to the author’s abusive misogyny and murderous rage.

The best-case scenario there would be the unlikely possibility that the author had been wholly successful at compartmentalizing his life and work, thereby allowing me to also keep those things wholly separate, allowing myself to be inspired or influenced by whatever I thought I found there without needing to worry that all of those ideas might be bound up with that body in the trunk — that they arose from or led to the same place for the reader as they did for the author. But you could never be certain that such a complete distinction could ever exist. No matter how wildly contradictory some of the author’s words might seem to be with his actions, it would never quite be possible to be utterly confident that those words weren’t still somehow a product of the same toxic sources from which those actions arose. You could never be sure that even the best bits of what you’d read weren’t carrying a hidden form of that toxin.

You wouldn’t be able to shrug this off with some glib “nobody’s perfect” rationalization because, after all, everyone is flawed and all your faves are problematic, etc. Yes, everyone may be flawed, but not everyone has such literal skeletons in their closet. You don’t want to invite a murderous misogynist into your head and allow him to settle in no questions asked.

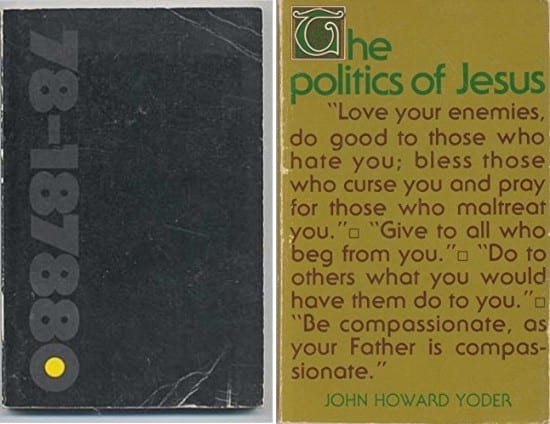

Unfortunately, none of this is hypothetical or abstract for me, personally, due to some of the other cursed objects I have here in my house: the books of John Howard Yoder. I only have two of those left, well-worn and heavily annotated copies of The Politics of Jesus and The Fullness of Christ. These were hugely important and influential books for me. Reading them — and re-reading them — changed my thinking and my faith and my life.

And that’s a big problem, because John Howard Yoder is a big problem.

Yoder, it turns out, was the Harvey Weinstein of Anabaptist theology. He raped and assaulted and abused and manipulated women. A lot of women.

And the way he did this was inextricably enmeshed with all of his profound ideas about power and love and coercion — the very same fine distinctions and revelatory insights that caused me to underline and double-underline so many passages in his books when I read them back before his deplorable double-life was publicly known.

I still have those books because I still don’t know what to do with them. I’ve thought about burning them or burying them in some kind of cleansing ritual, but I realize that would just be a way of further avoiding the necessary work I have to do. At some point I need to return to them to try to separate the truths they taught me from the lies I might also have learned from them. I need to figure out if such a separation is even possible, to discern whether it’s too dangerous to keep any of the influence and inspiration I once found there or if it’s best to just cut it out, cast it off, and cauterize the wound.

And to be perfectly honest, I’m still not sure how to do this. Contending with a book like The Politics of Jesus isn’t simple, or easy, or something I feel prepared to do with any confidence. But I know that I need to work on that book because I know that it is probably still working on me and I so I need to take great care to figure out what that means and what I’ll allow it to mean.

All of which is to say that I have great sympathy for my Southern Baptist cousins as they face a similarly uncomfortable and daunting task.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s “confession of faith” is a foundational, defining, identity-shaping document for the school. It was written by a slave-owner, a defender of and advocate for slavery who, when he wasn’t composing theological treatises, was buying and selling human beings, cheerfully participating in theft and kidnapping, torture, rape, imprisonment, abuse, and murder.

Maybe this thieving, human-trafficker/theologian had a preternatural ability to compartmentalize his life, and so his evil deeds had no influence on his piety and theology just as his piety and theology had no apparent influence on his evil deeds.

But maybe not. Probably not. It’s far more likely that his slave-trading influenced and shaped his theology in both direct and indirect. And it’s very likely that his theology reinforced and led to his actions as a thief and a human-trafficker. Following his theology, then, without extreme caution, could lead to a very bad place.

There is work to be done. For all of us. And it won’t be easy, or simple, or pleasant. But it is necessary.