Religion reporter Emma Green sits down with Georgia white evangelical mega-church pastor Andy Stanley for a post-election interview in The Atlantic: “The Evangelical Reckoning Begins.”

Green and Stanley both work hard to set the stage by explaining that Stanley isn’t one of those white evangelicals — not a die-hard, Fox-addled Trump worshipper.

Andy Stanley’s evangelical megachurch was empty on Election Night, with only a few cars in the Disney World–style parking lot out front. North Point Community Church and its nine satellites in the Atlanta area have been mostly closed since the coronavirus pandemic began in March. When Stanley decided to cancel in-person worship until at least early 2021, dozens of families were so unhappy that they decided to quit his church. “Never once did I hear, ‘We’re upset because we miss coming to church,’” he told me, leaning back in a heather-gray wingback chair. The vibe of his church offices is tasteful and inoffensive, as if his decorator was trying to channel that magic Fixer Upper quality of looking distinctive while appealing to almost everyone. “What I heard was, ‘We’re upset because you bought into a political agenda. We’re upset because you believe the Democrats’ narrative.’”

Stanley has spent his career in ministry deliberately avoiding this kind of politicization in his church. The 62-year-old pastor is a child of the religious right: His father, Charles Stanley, is a televangelist and former president of the Southern Baptist Convention who wrote the devotional that President George W. Bush used to read each morning. “I grew up in a family that was very, very right-leaning,” Stanley said. “I saw the hypocrisy there.” He yearned to reach people beyond the conservative Christian world, to make the story of the resurrection irresistible to the unchurched. So he rejected his culture-war inheritance and struck out on his own, and now the son has arguably surpassed the father: Andy Stanley leads a congregation of more than 37,000 adults and children each Sunday, second in size in the U.S. only to Joel Osteen’s Houston empire, according to some estimates. He’s written roughly two dozen books, mostly Jesus-y self-help, including one that came out in October called Better Decisions, Fewer Regrets. North Point has a network of about 90 churches around the world, and young Christian leaders flock to the church for guidance on how to expand their influence. Sam Collier, a Black pastor and friend of Stanley’s who is about to open Atlanta’s first branch of Hillsong, the Australian mega-ministry network, told me North Point is like “the Christian Gap.”

That observation — “the Christian Gap” — seems to be intended as a compliment, comparing Stanley’s church to the inoffensive, generic mass-appeal of the clothing chain. This is due, Green and Stanley both tell us, to Stanley’s determination to avoid being “political.”

That’s the strange thing about this strange interview in which Stanley constantly insists that he is not political. That’s what he tells us. What he shows us, however, is that Andy Stanley is a thoroughly, pervasively political man who just doesn’t understand that that’s what he is.

But while Stanley and similar giants inside the evangelical world have largely stayed out of politics during the Trump years, other evangelicals have been busy telling the outside world that their faith is completely aligned with Trumpism. This has created a dilemma: Stanley and his allies are now saddled with an image of evangelicalism they don’t want and didn’t create. Before they can reach anyone with a message of faith over politics, they’ll have to contend with the political baggage their fellow Christian leaders created.

In the Gospels, Jesus calls on his followers to go out, teach his message, and baptize people. Stanley has organized his life around this imperative, called “the Great Commission.” The question for evangelicals, now, is whether the undeniable association between Trump and their version of Christianity will make that work harder. “Has this group of people who have somehow become ‘evangelical leaders’” aligned with Trump “hurt the Church’s ability to reach people outside the Church? Absolutely,” Stanley said. But he’s not overly worried: A year or two from now, he said, “all that goes away.” New leaders will rise up. The Trump era of evangelical history will fade. Stanley chuckled. “And this will just be, for a lot of people, a bad dream.”

The invocation of the Great Commission there is weirdly hollow. It includes three things — “go out, teach his message, and baptize people” — but there’s no indication of what the middle one means. What is “Jesus’ message” that we’re greatly commissioned to go out and teach? That’s an even bigger “Christian Gap.” Apparently the message we’re meant to go out and teach is to convince others to go out and teach it too. I sometimes call this contentless form of the Great Commission “Amway without the soap” because it’s like the ultimate, purest form of multi-level marketing — one in which the need for any actual product is dispensed with entirely.

When we finally get around to Stanley’s scrupulously implicit politics, it doesn’t sound like anything informed by any identifiable aspect of Jesus’ “message.” It just sounds like what you’d expect from a well-off white guy in suburban Georgia:

Stanley …wouldn’t say who he voted for in the past two elections, but he volunteered that he’s a conservative guy with conservative values. His wife, Sandra, watches The Five on Fox News, and their family flips back and forth between the various cable networks. He’s never met the president, but after he told a friend that his foster daughter is a die-hard Trump fan, he received a personalized video from Trump telling her to do her homework. North Point’s original campus in Alpharetta largely leans Republican, he said. He understands Trump’s appeal. …

And then there’s this:

“If you’re asking me, ‘Did Donald Trump inflame, or make worse, or stir up racial tension?’ — I don’t know the answer to that,” he said. “I don’t know that I would place that on the shoulders of Donald Trump.” Many Black Christians have expressed pain over Trump’s racism. But Stanley wants to tread carefully: “I’m always hesitant to assign or accept simple, broad-brush explanations for anything. Especially events I have no personal involvement in or firsthand knowledge of.” He firmly supports the sentiment “Black lives matter,” but like a number of other prominent pastors, he says he’s uncomfortable with the organization behind the slogan. In a time of such intense political anger, putting faith before politics seems to involve grasping uncertainly at the line between speaking prophetically and making everybody mad.

Stanley wants to endorse the “sentiment” of the Civil Rights Movement without endorsing its aims. He’s not the first to make such an attempt. Hence the title of this post: “A Call to Unity.”

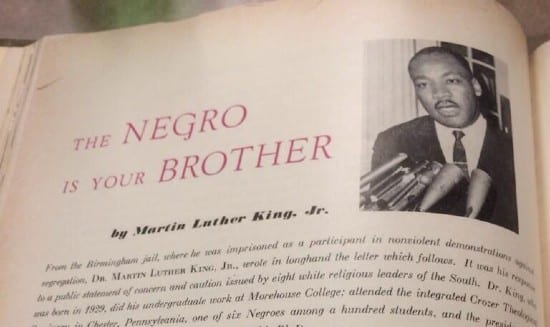

That was the title chosen by eight white religious leaders from Birmingham, Alabama, for their open letter scolding Martin Luther King Jr. as an outside agitator and asking him to leave. One of them was the pastor of that city’s most prominent Southern Baptist church, a man named Earl Stallings.

Andy Stanley reminds me a lot of Earl Stallings. Stallings fretted about Bull Connor the same way that Stanley frets about Donald Trump. He wanted to make sure people understood that he did not approve of that sort of thing. Not that he actually condemned it, mind you, but that he did not approve of it at all. Like Stanley, Stallings lived “in a time of intense political anger” and so his attempts to “put faith before politics” involved “grasping uncertainly at the line between speaking prophetically and making everybody mad.”

Alas for Stallings, he failed at both speaking prophetically and not making everybody mad. He decided as a gesture of support for the “sentiment” of the Civil Rights Movement to allow Black Baptists to attend an Easter service at his church. That earned him a canonical note of thanks from King himself, who wrote: “I commend you, Reverend Stallings, for your Christian stand on this past Sunday, in welcoming Negroes to your worship service on a nonsegregated basis.” But it also freaked out much of his all-white congregation, leading to his departure from the church just a few years later and then to the church’s eventual split.

More to the point, Stallings was mentioned by name in King’s Letter From a Birmingham Jail because he was one of the “Dear Fellow Clergymen” to whom that letter was addressed. Stallings was specifically and personally one of the “white moderates” King roasts in that letter:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress. I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that the present tension in the South is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

That’s the context of King’s “commendation” of Stallings for his “lukewarm acceptance.” A context made more fierce by the entirety of the paragraph in which that sentence appears:

Perhaps I was too optimistic; perhaps I expected too much. I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action. I am thankful, however, that some of our white brothers in the South have grasped the meaning of this social revolution and committed themselves to it. They are still all too few in quantity, but they are big in quality. Some — such as Ralph McGill, Lillian Smith, Harry Golden, James McBride Dabbs, Ann Braden and Sarah Patton Boyle — have written about our struggle in eloquent and prophetic terms. Others have marched with us down nameless streets of the South. They have languished in filthy, roach infested jails, suffering the abuse and brutality of policemen who view them as “dirty nigger-lovers.” Unlike so many of their moderate brothers and sisters, they have recognized the urgency of the moment and sensed the need for powerful “action” antidotes to combat the disease of segregation. Let me take note of my other major disappointment. I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership. Of course, there are some notable exceptions. I am not unmindful of the fact that each of you has taken some significant stands on this issue. I commend you, Reverend Stallings, for your Christian stand on this past Sunday, in welcoming Negroes to your worship service on a nonsegregated basis. I commend the Catholic leaders of this state for integrating Spring Hill College several years ago.

On behalf of justice, King says, some white Christians “have languished in filthy, roach infested jails, suffering the abuse and brutality of policemen.” But he adds that he is “not unmindful,” too, of the fact that after years of struggle, the Rev. Stallings also stepped up to allow Black Christians inside of his church building on Easter Sunday. The contrast is deliberate and unflattering.

One more nugget from Emma Green’s profile of white moderate Andy Stanley:

The secular world may believe “evangelicals” are nothing more than people who love Trump. Stanley happily uses the term Jesus follower instead. People within the Church, especially those who are Black or part of other minority groups, may be grieved over the way their brothers and sisters embraced Trumpism. Stanley has faith that they’ll stay in the fold. “This isn’t going to have long-term adverse effects on the Church, I’ll say that,” he told me.

Stanley is confident that the negative peace will soon be restored. Don’t worry, he says, reassuringly, in the long-term, nothing will ever change.