The “Redeemers” chose that deliberate language intentionally. This wasn’t because they were trying to disguise their political goals by describing them in religious terminology, but because those political goals were derived directly from their deepest religious convictions. They used the religious language of “Redeemers” and “Redemption” because they saw their political crusade as the true and necessary, God-blessed and God-ordained, biblical mandate of their faith.

They used language from their churches to describe the politics that also came from out of their churches.

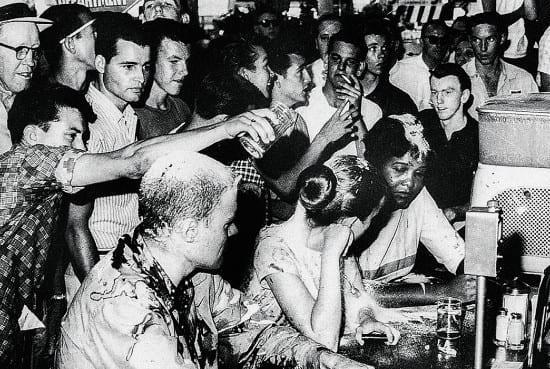

Nowadays, we don’t usually use that same language for the self-proclaimed “Redeemers” and their successful campaign of “Redemption.” We just call them the Klan or Lost Causers or Neo-Confederates — the violent, lawless, white supremacist criminals who strangled Reconstruction in its crib. We don’t usually call their political agenda and political victory “Redemption,” we just call it Jim Crow or segregation or institutionalized racism.

Adopting such secular terminology for what was then — and still is — an explicitly and pervasively religious crusade, has caused most of us to forget, or to refuse to see, how the politics of Redemption/Jim Crow/segregation/the Klan were inseparable from the white Christianity that fueled them. And it has caused most of us to forget, or to refuse to see, how those same politics still are inseparable from the very same, unchanged and un-Reconstructed white Christianity that still fuels them.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s was America’s Second Reconstruction, a time when massive, nonviolent protests managed to force the courts to finally enforce some measure of the new Constitution forged in the first Reconstruction. It was swiftly followed by the Second Redemption, in which we are still living today.

If I were forced to pinpoint a specific moment for the transition, I suppose I would put it at the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. That would mean that I have been living within the Second Redemption for my entire life. I was born into it and I was born again into it — within the same American white church teaching the same American white Christianity that had informed and required the century-long period of the first Redemption. This is the white Christianity into which I was baptized and in which I was discipled.

This is a bleak assessment of American history and of the role of white Christianity in that history. And it’s a very bleak assessment of the nature of white Christianity throughout American history. It’s a framework that I probably first saw, and recoiled from, more than a decade ago — reluctant to accept it because of that awful bleakness. But over the years — especially over the past five years — that reluctance has been worn away by the fierce daily evidence. The fact of the Second Redemption is no longer, for me, a theoretical framework providing some insights into our religion and politics. It is now a grim but necessary conclusion supported by every bit of theological, cultural, and political evidence I have seen.

Anthea Butler speaks the truth here, “White evangelicals, don’t just condemn Christian nationalism. Own it“:

Here’s the hard, ugly fact: Evangelicals support the racism, sexism and violence done on their behalf by so-called Christian nationalists. Black Christians have seen this for more than 400 years. We are not surprised, and these evangelical writers shouldn’t be either. Evangelicals’ politics are about their power. They use morality to hide their thirst for it.

Evangelicals know full well the ugliness and perfidy of the people they vote into office, support with their dollars and those they listen to every Sunday in pulpits across the nation. They claim to hate the ugliness, yet they remain in the same pews and support the same political leaders.

The Southern Baptist Convention has spent considerable time in the past year condemning critical race theory, first with a resolution at their 2019 annual meeting and most recently with a statement from six Southern Baptist seminary presidents proclaiming that the theory is incompatible with the denomination’s statement of faith.

The SBC’s position on CRT conveniently dovetails with the Trump administration’s recent Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping, which cuts out “blame focused” diversity training at federal workplaces. Diversity training shows the inequities of life for many ethnic groups in America. The only ones who may be uncomfortable with those inequities being called out are those who are still perpetuating them.

The Black church has also come under fire from Republican politicians who love to visit Black churches for photo-ops but balk at the convicting message of the gospel. The upcoming runoff in the Georgia Senate race is an excellent example. Senator Kelly Loeffler, who attended a commemoration on Martin Luther King Jr. Day at Ebenezer Baptist Church in January, is now digging up old sermons by Ebenezer’s pastor, the Rev. Raphael Warnock, to twist and misrepresent Warnock’s words (and the gospel itself).

… When white evangelicals ignore race as the motivating issue, I doubt their witness. Their handwringing, the self-abnegation, is meant to assuage their own discomfort, rather than the discomfort, violence and continual distress of Black people in America. I invite them to back up their words with actions, to reach out to those in the crossfire of this racial storm, to stand up against the leaders and associates in your denominations who remain silent because they voted for chaos instead of community.