Here’s Daniel K. Williams at the Anxious Bench: “Will Reformed Evangelicalism Divide Over Racial Politics? The 19th-Century Stone-Campbell Movement Offers a Clue.”

On the one hand, this is a terrific example of how studying history can provide insights about the present. Williams’ knowledge of the conflicts within the Stone-Campbell Restorationist stream of American evangelicalism back in the 1850s allows him to recognize some real similarities with the conflicts today within the “young, restless, and Reformed” strand of American evangelicalism. That helps him clarify the internal and external factors that are pushing for and against the unity of this branch of the church.

Williams doesn’t pretend that knowledge of history allows us to simply predict the future, but his discussion illustrates how it can help us better understand and navigate the present and the sort of future our present choices may be creating.

On the other hand, though, this is all whiter than a blank sheet of paper.* And that makes the whole exercise more than a little bit off.

The unspoken, implicit whiteness of both of these stories doesn’t undermine Williams’ historical parallel, it deepens and strengthens it. If presumed whiteness is an unacknowledged blind spot in his essay, it’s also the unacknowledged blind spot in the conflicts he describes among both groups. It’s the factor that makes the parallel particularly apt. Sure, a bunch of 19th-century Arminians not seem to have much in common with a bunch of Very Online 21st-century Calvinists, but those differences seem trivial — mere noisy gongs and clanging cymbals — once we recognize the overriding similarity of two white groups of white Christians seeking to preserve the whiteness of their white doctrines.

Here’s Williams on the similarities between the two groups:

Both movements were strongly biblicist, both favored rational and logical appeals over emotional displays, and both promised a textual and theological pathway to the restoration of the original Christian message. … But perhaps most significantly, Stone-Campbell Restorationism paralleled the “young, restless, and Reformed” movement in its view of the church’s relationship to politics; although interested in social and political reform causes, many members of the movement believed that the restoration of the New Testament church offered a pathway to social reform that was superior to what any political party could advocate. The only problem was that the members of the movement could not agree on what that pathway should be. Nowhere was this more evident than on the issue of slavery.

This is a pillar of white Christianity, what later white Southern Presbyterians called “the spirituality of the church.” It’s the idea that yestbutofcourse “social reform” is all very well and good, but it must come about through the church and through religious conversion and not through anything as secular and worldly as politics. White Christianity is thus a-political — except for all the ways in which it never is and never can be.

In the 19th century, as Williams discusses, this meant that abolitionism was regarded as inappropriate meddling in politics, while maintaining the status quo of slavery or advocating a flaccid, theoretical gradualism was not. In the 20th century, white Christians regarded the struggle for integration as a violation of the bold line prohibiting church involvement in “politics,” while the defense and practice of segregation was not.** And in the 21st century, as Williams notes, this dispute among white Christians about what does and does not constitute “politics” involves Black Lives Matter and other contemporary white disagreements over the legitimacy of the Reconstruction Amendments and the legal equality of Black Americans. Inequality is always a-political and spiritual while every closer approximation of equality is “racial politics” (controversial, divisive, and un-spiritual).

In the 19th century, as Williams discusses, this meant that abolitionism was regarded as inappropriate meddling in politics, while maintaining the status quo of slavery or advocating a flaccid, theoretical gradualism was not. In the 20th century, white Christians regarded the struggle for integration as a violation of the bold line prohibiting church involvement in “politics,” while the defense and practice of segregation was not.** And in the 21st century, as Williams notes, this dispute among white Christians about what does and does not constitute “politics” involves Black Lives Matter and other contemporary white disagreements over the legitimacy of the Reconstruction Amendments and the legal equality of Black Americans. Inequality is always a-political and spiritual while every closer approximation of equality is “racial politics” (controversial, divisive, and un-spiritual).

The white Christians of the white Stone-Campbell Restorationist movement could not agree on what their white doctrines required of them regarding “the issue of slavery.” The white Christians of the white “young, restless, and Reformed” movement cannot agree on what their white doctrines require of them regarding slavery either. And in both cases, this disagreement — this confusion and lack of clarity — is a product of whiteness.

What should the white church’s “pathway to social reform” be with regard to “the issue of slavery”? White Christians couldn’t say because it never occurred to those white Christians to ask Black Christians for guidance. Because all of this talk about the glories of “Christian unity” has never extended to include non-white Christians or non-white Christianities. And all this talk about the horrors of “division” and “disfellowship” has never applied to the non-white Christians just down the road.

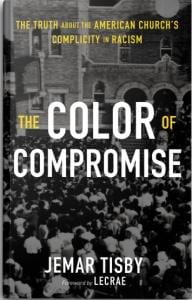

I happened to read Williams’ post just after listening to this podcast: “PTM: Leave LOUD- Jemar Tisby’s Story.” Tisby was, for several years, a rising star in that “young, restless, and Reformed” movement (one with a better claim to “young” than most of its leaders). And then he wasn’t.

What happened? That is, in part, the story of the subtle ways that whiteness works to exclude non-whiteness, the ways that whiteness gets enshrined into doctrines allowing the enforcement of whiteness to be exercised as a “spiritual” discipline of maintaining doctrinal orthodoxy.

But it’s also in part a not-at-all subtle story of explicit white power and unadulterated white-nationalist, Neo-Confederate racism indistinguishable from any of those 19th-century arguments among white groups of white Christians. Which is to say, it’s in part the story of how a movement that makes space for Doug Wilson cannot also be a movement that makes space for Jemar Tisby. Give it a listen. (It’s compelling, lively, sometimes heart-breaking/enraging and sometimes funny — and unlike many podcasts, it doesn’t include any awkward segues into trying to sell you a new mattress or to use Stamps.com.)

Having Tisby’s voice still echoing in my head let me see what’s missing in Williams’ discussion. It’s the same thing I addressed a while back as “The Hole in Noll“:

[Noll provides] an immensely helpful, perceptive and illuminating discussion of the way antebellum American Christians were wrestling with what the Bible had to say about slavery. I think it should be required reading for anyone trying to understand American Christianity. It captures the essential dynamic — the fact that how American Christians read the Bible shaped how they responded to slavery and that how American Christians responded to slavery shaped how they read the Bible. The influence of slavery remains just as true today as it was in the early 19th century.

But, also, not.

Because actually that’s an immensely helpful, perceptive and illuminating discussion of the way antebellum white American Christians were wrestling with what the Bible had to say about slavery. I think it should be required reading for anyone trying to understand white American Christianity. It captures the essential white dynamic — the fact that how white American Christians read the Bible shaped how they responded to slavery and that how white American Christians responded to slavery shaped how they read the Bible.

What about Black Christians — lay people and theologians? There were millions of Black Christians in America during the first half of the 19th century — where do they fit in Noll’s scheme?

They don’t.

Noll acknowledges this, almost parenthetically, in The Civil War as Theological Crisis. After laying out all these various views among the disputatious [white] Christians, he briefly turns to consider the voices and arguments made by Black Christians at the time. That discussion is brief partly because it provides no contentious debate that needs summarizing. Among Black Christians, there were no credible voices arguing the proslavery side.

But the important thing there is not the unanimity of Black Christians in their opposition to slavery. The important thing there — what should be, for all Christians, everywhere, the most astonishingly important thing — is that America’s Black Christians were right.

We can say this. Definitively. Without qualification.

When it comes to the single largest question in American history — the single largest theological question and hermeneutic question that has ever faced the church in North America — white Christians were squabbling and divided. White Christians were wavering and uncertain and all over the map. White Christians, for the most part, got it wrong.

Black Christians, almost without exception, got it right.

I’m less interested in whether any given group of white Christians will be able to maintain a tenuous white Christian white unity than I am in whether those white Christians might someday start wanting to get right what they have, up until now, always gotten wrong.

* The title of this post comes from a dumb joke from grade school. Kid holds up a blank piece of paper and says it’s a picture of a cow eating grass.

“Where’s the grass?”

“The cow ate it all.”

“Well, where’s the cow?”

“It went to look for more grass.”

And that’s kind of the level of sheer whiteness we’re talking about here.

** Hence the standard narrative of white evangelicalism which describes a retreat from “politics” post-Scopes Trial before an eventual re-engagement with politics in the late ’70s. So all those white evangelicals shouting in the background of all those pictures of Ruby Bridges or the Little Rock Nine? Totally a-political. That’s the “spirituality of the church.”