Joshua Rivera has written a lovely, thoughtful personal testimony for Slate: “Vanished From the Earth.”

“As an evangelical kid,” Rivera writes, “I was terrified of the Rapture.” And he goes on to describe the forms of that terror — the Rapture anxiety and Rapture fears that will be familiar topics to long-time readers of this site:

Other evangelical kids I knew growing up would tell me about their own first Rapture scares. They were always triggered by mundane things: Somebody came back from school one day and no one was home. Or someone’s parents didn’t answer a phone call the way they normally would have. In an instant, the cosmic outlook we’d been instilled with for our entire young lives would coalesce with shocking clarity: Was this it? Had the Rapture happened? Were we going to face judgment alone?

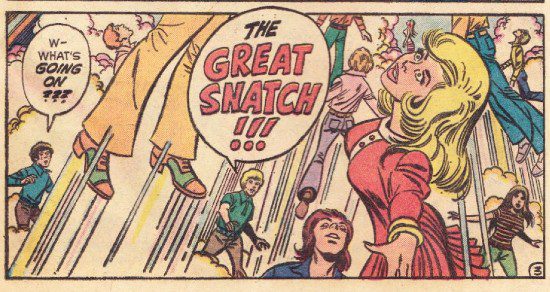

But Rivera didn’t grow up reading Hal Lindsey’s books (and comic books) in the 1970s and ’80s. He never watched A Thief in the Night or the guillotine scene in A Distant Thunder via a cheap projector in a church basement. Those are the Gen-X experiences of growing up immersed in white evangelical Rapture folklore, and Rivera is too young to have lived through that time. Rivera’s parents are my age, so he’s not quite even old enough to have experienced the high tide of Left Behind’s popularity, when Tim LaHaye eclipsed Lindsey as the foremost peddler of this pop theology.

Rivera is, like me, a third-generation Rapture evangelical — someone raised from childhood to believe in the pseudo-gospel of the Rapture by Christian believers who had themselves been raised from childhood to believe in this imminent and ultimate End of All Things. And in his case, as in mine, that third generation proved to be unsustainable. His essay discusses the Great Disappointment of the 19th-century Millerites, which illustrates why it’s nearly impossible to hold on to the claim of urgent imminence for a third generation. Failed predictions have a way of piling up that becomes harder to ignore for us than it was for our parents and grandparents.

As we discussed here back in January (“Teaching Hal Lindsey to teenagers in the ’80s was child abuse“), growing up in the third generation of Rapture “prophecy” means you’re unable to take such failed prophecies seriously — and you’re forced, instead, to take seriously the realization that your preachers and teachers promoting this stuff don’t really take it seriously either. (“The world is surely going to end before you’re 30,” they tell you. And then they urge you to study hard so you can make a good living for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.)

But the biggest difference between Rivera’s family history of Rapture mania and my own is not just that it’s one generation later — that his grandparents were my parents’ age and his parents are my age. The biggest difference is that his family is far closer than mine to being the intended audience for the apocalyptic literature from which this Rapture theology was concocted.

The thing about apocalyptic literature is that if you’re privileged and educated enough to toss around terms like “apocalyptic literature,” then it’s unlikely you’re the intended audience for it.

And if you’re not the intended audience for that apocalyptic literature, then you’re not likely to understand it, which is to say you’re quite likely to misunderstand it — to misread it as though it was something that was written for you. It is literature — scripture — written by and for the exiled and the oppressed, and readers who are not among the exiled and the oppressed are ill-equipped to comprehend it.

Imagine Pharaoh reading the book of Exodus. He wouldn’t get it. Or he would get it wrong. Because it wasn’t written for him or to him.

Now imagine Pharaoh re-writing the book of Exodus. That’s Rapture theology.

The genre of apocalyptic literature isn’t very common in recent centuries, but we can still find a few examples. One of my favorites is this song, made famous by Nina Simone:

Apocalyptic doom is coming for the Sinnerman, but this isn’t a fire-and-brimstone sermon with a white revivalist preacher calling on sinners to repent of their individual misdeeds. This is a Magnificat, a song of Deborah, and the Sinnerman in question is Pharaoh himself (note the rivers turning to blood). The revivalist warns of what will happen if the sinner doesn’t repent, but the Magnificat and the apocalypse scarcely hint at any hope for Pharaoh or Sinnerman. The rich will be sent away empty and the thrones of the powerful will be toppled and where they gonna run to on that day? Nowhere. If repentance is an option for the Sinnerman, it is an option he will have to introduce himself when he is at last forced to see he has nowhere else to run and is reduced to begging to be shown the mercy he has refused to show to others.

Peter Tosh revisited the same song, taking a Rasta-inflected cue from the prophet Isaiah by dismissing the distraction of lesser “sins” to focus on the grave evil of oppression and injustice. “Downpressor Man” is, again, apocalyptic literature — written by and for the downpressed:

This song is an expression of hope for eventual, but inevitable justice. But the promise of justice is only a hopeful thing for those who have been denied justice. For those who have been doing the denying, it’s a grim warning.

Josh Rivera talks about how the promise of long-delayed, eschatological justice has been a source of hope for his working-class Rapture-devoted parents:

My father still goes to the same church I haven’t been to in five years. He still believes many of the same things. He works for a telecommunications company, making sure the servers and circuitry that bring the internet to you don’t shut down. He knows his overtime hours will never accrue into meaningful wealth; he knows that despite his best efforts he is one bad day from losing his home, his car, his life. He sits in a congregation of Hispanic people who are also aware of this, the filthy cheapness of life.

So they make a bargain, the only one that makes sense, the one that countless others have made in countless pews: They will stake their claim on the imagined apocalypse of the Rapture because, at the very least, that is the doom that will save them in the end. If they’re wrong, they get what’s coming to them anyway: an unremarkable death in a world that was hostile to them, their hopes firmly planted on what comes next.

But notice the difference between the tangible this-worldly doom of “Sinnerman” and the ethereal, otherworldly hope of this Rapture business. It surrenders any hope of justice in this world or in this life, offering only the escapism of “I’ll Fly Away.”

The Rapture, in other words, is a neutered, nerfed, defanged counterfeit version of the songs sung by Mary and Deborah and Nina. Their pronouncements of the hope and warning of long-denied justice are safely repackaged into forms that no Pharaoh or Nebuchadnezzar or Nero or Jim Crow ever needs to fear. The white theology of the Rapture tames the dangerous, destabilizing, dethroning theology of the apocalyptic. It turns it into not just an opiate of the masses, but an opiate for the oppressor. It takes the terrifying warning of “Sinnerman” and turns it into a reassuring, comforting dream that can be a source of solace not just for those whose lives are treated cheaply, but for those who are making those lives cheap and benefitting from their cheapness.