There are a bunch of miracles in the stories recounted in 1 Kings 17. The first one is unpleasant — a severe drought sent by God to punish the evil King Ahab:

Now Elijah … said to Ahab, “As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, whom I serve, there will be neither dew nor rain in the next few years except at my word.

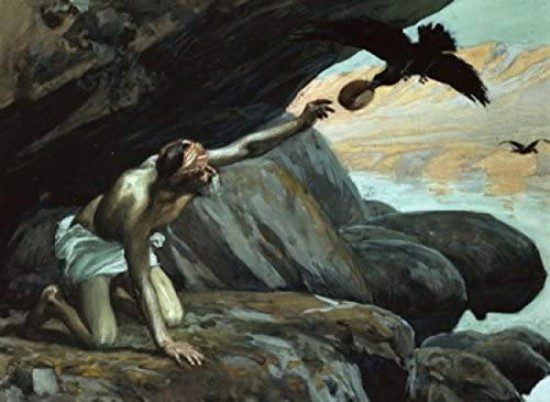

This drought is a heavy punishment for all the people of Israel, including Elijah himself, but God provides for the prophet by sending him east of the Jordan, to a small brook where he will have water to drink. God also makes sure Elijah has food to eat thanks to the second miracle in this story: “I have directed the ravens to supply you with food there,” God tells Elijah. And “The ravens brought him bread and meat in the morning and bread and meat in the evening.”

Eventually, though, the drought dries up the brook, so God sends Elijah far away in the opposite direction: “Go at once to Zarephath in the region of Sidon and stay there. I have directed a widow there to supply you with food.”

This is odd for a couple of reasons. First because he’s going to Sidon, which already featured earlier in this story as the birthplace of Jezebel, the Sidonian princess who marries King Ahab of Israel and leads him to adopt her Sidonian religion. And second because, unlike the ravens, the widow of Zarephath doesn’t seem to have been told about God’s plan for her to supply Elijah with food:

So he went to Zarephath. When he came to the town gate, a widow was there gathering sticks. He called to her and asked, “Would you bring me a little water in a jar so I may have a drink?” As she was going to get it, he called, “And bring me, please, a piece of bread.”

“As surely as the Lord your God lives,” she replied, “I don’t have any bread — only a handful of flour in a jar and a little olive oil in a jug. I am gathering a few sticks to take home and make a meal for myself and my son, that we may eat it — and die.”

Which sets the stage for miracle No. 3:

Elijah said to her, “Don’t be afraid. Go home and do as you have said. But first make a small loaf of bread for me from what you have and bring it to me, and then make something for yourself and your son. For this is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: ‘The jar of flour will not be used up and the jug of oil will not run dry until the day the Lord sends rain on the land.'”

She went away and did as Elijah had told her. So there was food every day for Elijah and for the woman and her family. For the jar of flour was not used up and the jug of oil did not run dry, in keeping with the word of the Lord spoken by Elijah.

So amidst all the wickedness of Ahab and the divine wrath of Elijah, we get this sweet little story about the miraculous hospitality of a desperately poor Phoenician widow. There are echoes here of lots of other biblical stories about not-enough miraculously becoming enough when it gets shared. That happens with manna in the wilderness and with loaves and fishes on the hillside in Galilee. It’s kind of a major recurring theme in both the Hebrew and Greek scriptures.

This story also has echoes of lots of other biblical stories and other ancient stories emphasizing the duty of hospitality. Some of those stories, like this one, are happy stories of generosity and miraculous plenitude. Others aren’t so positive — emphasizing the taboo wickedness of denying hospitality. Think of Procrustes, or of the Nasty 19s (the stories told in Genesis 19 and Judges 19).

The Phoenician widow in this story extends as much hospitality toward Elijah as she is able. She brings him water when he asks. But she apologizes for having to say “no” when he asks from her more hospitality than she is able to provide. When he asks for bread as well, she tells him that she is unable to give him any as she has only just enough for one final meal with her child, after which they will both quietly die of starvation.

At this point in the story, Elijah tests her faith. He promises her a miracle, telling her that she and her son don’t have to die. But while this tests her faith, Elijah isn’t a jerk about it. He scales back his initial request, asking only for “a small loaf,” and then immediately reassures her that if she does this, she and her son will be provided for, in perpetuity. He doesn’t test her hospitality and then reward her with this miraculous provision only after she passes that test. And Elijah doesn’t threaten her the way he often threatens the rich and the powerful in other stories. He says “Bring me what little bread you can manage and I will make sure you and your child can survive,” not “Give me the last of your bread, or else I will let you and your son die.”

(He also never at any point compares her or her child to “dogs,” so Elijah comes across a bit better here than the protagonist of the other famous Bible story involving a desperate Phoenician widow.)

This is an important Bible story because hospitality is an important thing. Hospitality is an important moral duty.

But hospitality is also a contingent duty. In this story, the widow was obliged to provide water for Elijah because she was able to do so. But she was not obliged to starve her own son in order to provide bread for Elijah. She had no bread and therefore no obligation to share it.

The duty of hospitality, in other words, can never be made into a weapon used to force someone to give what they cannot give. The duty to share applies only to those who are able to share.

It would be cruel, monstrous, and absurd to suggest that a poor widow without bread had a moral duty to provide bread for Elijah. The story presents her initial hospitality — sharing water — as evidence that she is a good person. Her refusal to share bread she does not have is not presented as evidence that she is a bad person. The story and Elijah himself do not condemn her for that.

Once the widow of Zarephath becomes both the recipient of and the conduit for miraculous divine providence, she’s presented as more than merely a decent person fulfilling her bare-minimum moral duty. She goes beyond mere moral duty to engage in a heroic, supererogatory form of generosity and hospitality, one that is not and cannot be expected, required, or mandated. She is rewarded for that supererogatory goodness by Miracle No. 4, when Elijah raises her son from the dead.

All those miracles — those exceptional acts of divine intervention — make it a bit trickier for us to seek ethical guidance from this story. We can’t presume miraculous intervention when trying to decide what the right thing to do should be any more than we can presume to direct the ravens to bring meat and bread to the hungry.

But I think this story helps us to understand the moral obligation of hospitality and the limits of that obligation. Hospitality is always a Good Thing, but we cannot insist that it is a mandatory thing for those unable to provide it. If we find ourselves chastising a starving mother for inhospitality because she has no bread left to share, we’re doing something wrong — something both incorrect and immoral.

Hospitality toward the poor is a duty. Demanding hospitality from the poor is tying up heavy burdens hard to bear and laying them on the shoulders of the powerless. Insisting on a duty of hospitality from those unable to provide it takes us away from the territory of the story of Elijah and the Widow of Zarephath and into the territory of the story a few chapters later of Ahab and Naboth’s vineyard. It’s not morality; it’s an abomination.